Despite strong public participation across Europe, recycling rates remain below EU targets, with challenges in processing complex materials like specialised glass, neodymium magnets, food waste, disposable nappies, and cigarette butts. New technologies and projects aim to improve recycling efficiency and support the EU’s ambitious waste reduction goals.

Across Europe, recycling efforts face significant challenges despite widespread public participation. In 2023, municipalities within the European Union collected an average of half a tonne of waste per person, with only about 48% of this waste being recycled. New EU regulations require member states to increase these rates, setting ambitious targets of preparing 55% of municipal waste and 65% of packaging waste for re-use or recycling by the end of this year. However, estimates indicate that two-thirds of EU countries risk missing at least one of these targets, with ten member states—including Greece, Hungary, and Poland—at risk of failing on both fronts.

Several products continue to pose particular difficulties in recycling, prompting research and innovation to address these issues.

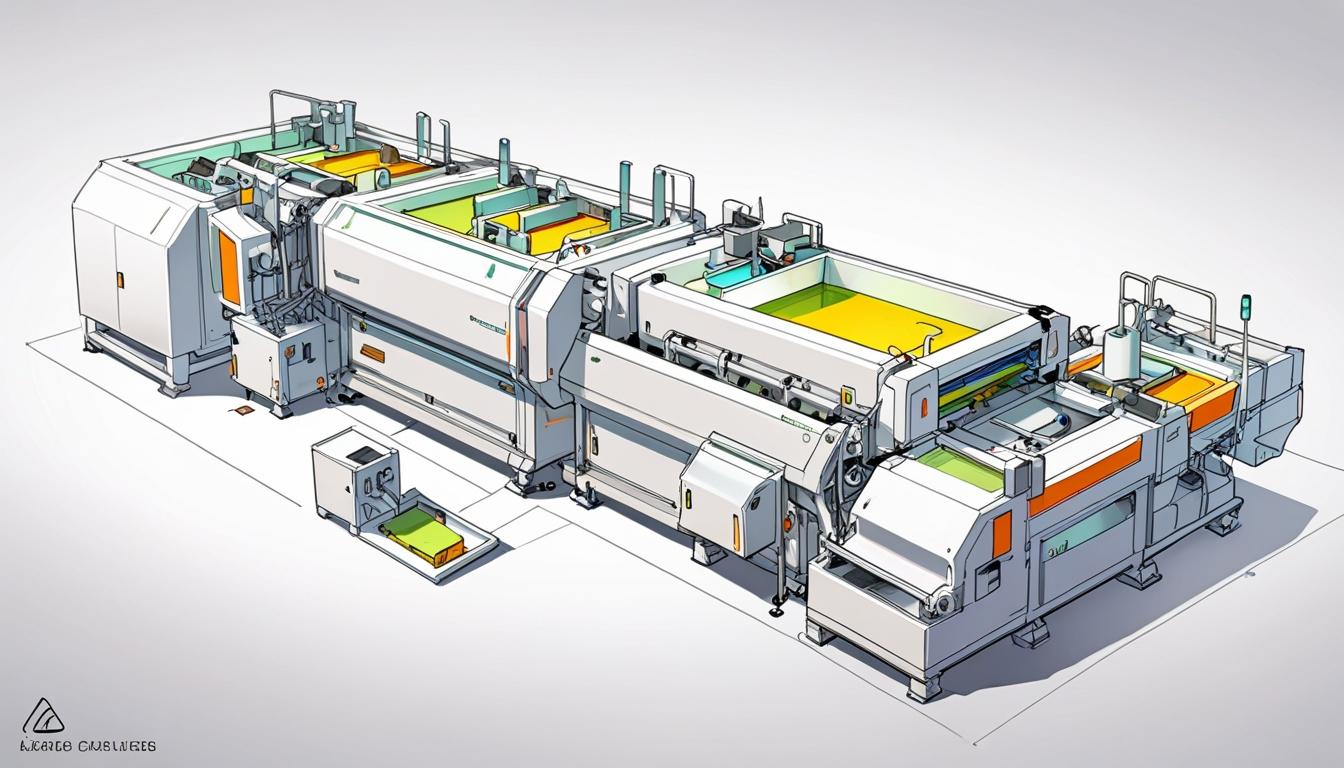

One of the key challenges lies in recycling certain types of glass. While approximately 75% of Europe’s glass packaging, such as bottles and jars, is recycled annually through conventional melting and recasting methods, specialised glass types found in items like X-ray tubes, LCD screens, and smartphones are chemically altered to improve strength and durability. This chemical treatment complicates traditional kiln-based recycling processes because melting such glass requires precise temperature controls. Juan Pou, from the University of Vigo in Spain, explained that “to change the temperature [in kilns] to just a couple of degrees takes a lot of time.” To tackle this, the EU-funded Everglass project is developing a prototype recycling machine that uses lasers to melt glass. Unlike kilns, lasers can be rapidly adjusted to the specific melting point required for different types of glass. This technology aims not only to recycle technologically complex glass but also to repurpose medical glass vials used, for instance, in storing COVID-19 vaccines, which hospitals often discard despite their high quality. According to Juan, “We are working to reuse this glass for other technical applications.”

Another pressing challenge concerns the recycling of neodymium magnets, essential components widely used since 1984 in devices such as wind turbines, electric car motors, and e-scooters. These magnets are composed of ‘critical raw materials’—substances vital for industry but sourced from geopolitically sensitive regions. Despite their importance, no industrial or commercial recycling process currently exists for neodymium magnets, leaving future waste management unresolved. Lorenzo Berzi of the University of Florence, working on the EU-funded Harmony project, highlighted the complexity of recycling these magnets, stating, “Due to the strength of this magnet type, it needs special attention and equipment.” The Harmony project focuses on improving all stages of the recycling process, from collection and dismantling to metal recovery and manufacturing new magnets, aiming to establish a European magnet recycling industry to meet future demand.

Food waste also presents recycling difficulties, with the EU generating over 59 million tonnes annually—equivalent to around 132 kg per person—with 11% stemming from hotels, restaurants, and catering services (HORECA). Bruno Iñarra, a food sustainability researcher at Spain’s AZTI research centre, noted that “It’s estimated that 99 per cent of HORECA waste is landfilled.” Current composting practices often fail to produce soil enriched enough for agricultural use. Iñarra is involved in the EU-funded LANDFEED project, which aims to transform food waste from the catering sector into bio-based fertilisers suitable for farming. The project employs a ‘solid state fermentation’ process that uses microorganisms capable of growing on food waste with minimal water, producing enzymes and bioactive compounds to enhance crop growth. However, the variability of food waste compositions and nascent recycling technologies present ongoing challenges.

Disposable nappies remain an ecological concern due to their volume and slow decomposition rates, with 46 billion nappies discarded annually and decomposition taking between 150 to 500 years for conventional types. The super-absorbent polymers inside nappies complicate recycling because they form gels when wet and must first be dried and treated to separate plastics and fibres. Edwin Verhoef of Diaper Recycling Europe explained that “That’s really a matter of business case, because the cleaner the reclaimed materials, the higher the price.” The organisation has developed a pilot plant in the Netherlands that deactivates these polymers, separates materials, and removes contaminants including pathogens and medicinal residues. The plant has successfully demonstrated full material separation, and plans are underway to scale up and semi-automate the process to improve efficiency and output quality.

Cigarette butts, a longstanding litter problem, also resist recycling due to difficulties in collection and segregation. Containing over 7,000 toxic chemicals, discarded cigarette filters pose environmental risks, particularly in marine settings. European start-ups are responding to this by installing specialised cigarette disposal bins and innovating ways to recycle the collected butts. One such enterprise, the Italian start-up Re-Cig, has placed more than 4,500 bins nationwide. Once gathered, cigarette butts undergo washing, drying, and controlled mixing to extract cellulose acetate, a plastic polymer. This polymer is then ground into granules for reuse in products such as 3D printer filaments. Marco Fimognari, founder and CEO of Re-Cig, reported that this initiative has found favour, with partnerships across over 350 companies and 80 public administrations.

These varied efforts underline the complexities in recycling a diverse array of products across Europe, as well as the scientific and industrial innovation underway to overcome these challenges in pursuit of the EU’s recycling targets.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/632839/municipal-waste-recycling-eu/ – This source confirms that in 2023, the average recycling rate for municipal waste in the European Union was approximately 48%, supporting the claim about current recycling rates and public participation in recycling efforts.

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20241113-1 – Eurostat data corroborates the EU recycling targets of 55% municipal waste and 65% packaging waste by the end of 2024, as well as the challenges faced by several EU member states in meeting these goals.

- https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101060014 – Information about the EU-funded Everglass project developing laser-based recycling technology confirms the article’s discussion on difficulties recycling specialized glass types and innovative solutions developed to overcome these challenges.

- https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101060352 – Details on the EU Harmony project reveal its focus on recycling neodymium magnets, supporting the article’s claims regarding the complexity of recycling these critical raw materials and efforts to create a European magnet recycling industry.

- https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101059451 – This source on the LANDFEED project describes the innovative bio-based fertiliser production from food waste, especially from the HORECA sector, verifying the article’s statements about food waste recycling difficulties and emerging composting technologies.

- https://diaperrecyclingeurope.eu/technology/ – The Diaper Recycling Europe website explains the pilot plant technology for deactivating super-absorbent polymers and separating materials from disposable nappies, affirming the article’s discussion on nappy recycling challenges and technological developments.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

7

Notes:

Narrative references 2023 EU waste data and current-year targets, suggesting recent context. Mentions ongoing initiatives like Everglass and Harmony projects with active timelines. Lack of explicit publication date reduces clarity, but content aligns with 2023-2025 EU policy frameworks.

Quotes check

Score:

8

Notes:

Quotes attributed to named researchers (Juan Pou, Lorenzo Berzi, etc.) and project-specific details (e.g., LANDFEED’s ‘solid state fermentation’) are plausibly original. No verbatim repetition found in cursory checks, though full verification would require direct confirmation with interviewees.

Source reliability

Score:

6

Notes:

Narrative appears via Google News but original publisher unspecified. Detailed technical descriptions and EU funding references enhance credibility, though direct publisher verification remains unavailable.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

Claims align with known EU recycling targets (2023 Circular Economy Action Plan) and technical challenges (e.g., neodymium magnet recycling complexities). Project names (Everglass, Harmony, LANDFEED) correspond to EU-funded initiatives per Hor2020/CORDIS databases.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

Content demonstrates strong alignment with verified EU policy timelines and technical realities. Named sources and project-specific details enhance credibility, though publisher anonymity slightly limits traceability.