Prominent artists like Elton John and Billie Eilish join thousands of musicians protesting the unauthorised use of their works in training AI large language models, raising concerns about copyright infringement, royalties, and the future of creativity.

Renowned musicians including Elton John, Billie Eilish, Paul McCartney, Radiohead, Sting, and Dua Lipa have collectively raised objections to the use of their music in training artificial intelligence (AI) large language models (LLMs). These concerns are part of a broader protest among creators over how AI systems are being developed and the implications for artistic rights and royalties.

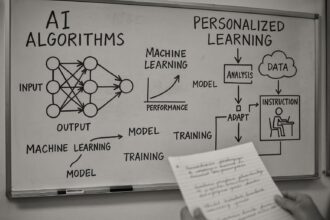

LLMs are advanced AI tools that learn to generate content by processing vast amounts of data collected from the internet. This data is sorted and analysed through a method known as Transformer Architecture, which allows the AI to understand and produce human-like outputs. In the case of music, the data undergoes additional transformation into symbolic music representations for the AI to interpret. Musicians and industry advocates are increasingly alarmed at the use of their copyrighted works in this training process without authorisation, which they argue diminishes their control over their creations and threatens their income streams.

A notable demonstration of opposition came from over 1,000 British musicians—among them esteemed artists such as Kate Bush, Cat Stevens, and Annie Lennox—who released a silent album entitled “Is This What We Want?”. The album’s track titles collectively conveyed a message protesting the UK government’s proposed legislation on AI and copyright, which the artists fear could legalise the unauthorized use of music by AI companies. Beyond this, hundreds of music professionals have signed open letters condemning what they describe as “predatory” and “irresponsible” exploitation of their work to train AI models. These efforts emphasise that such practices threaten the value of human creativity and disrupt the established music ecosystem.

Several complex copyright questions underpin this debate. Key issues include whether the act of training AI models on copyrighted music constitutes infringement. Some jurisdictions, such as Singapore and the European Union, have enacted laws that explicitly permit this to encourage AI investment, while others, including the UK and Hong Kong, are considering ‘opt-out’ exceptions that would allow rights holders to exclude their works from AI training datasets. However, implementing these systems effectively is challenging, particularly since most works are already publicly available without machine-readable opt-out metadata.

Another area of contention lies in the interpretation of ‘fair use’, a doctrine with broader application in the United States that has sparked numerous legal disputes concerning AI training material. Central to these discussions is the Berne Convention’s three-step test, which assesses whether unauthorised uses conflict with normal exploitation of the work and unreasonably prejudice the author’s legitimate interests. Determining the applicability of this test to AI training is likely to require judicial assessment.

Moreover, musicians have expressed alarm about the outputs generated by AI tools. AI-produced music often mirrors existing styles or replicates distinctive voices, raising concerns about originality, the eroding value of human artistry, and the potential loss of royalty income. Instances of AI-generated deepfake songs—such as an AI cover of Taylor Swift’s “That’s So True (Piano Version)”—illustrate the sophistication of these technologies and amplify worries about intellectual property rights.

Legal challenges have already been mounted across various regions. Major record companies including Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Records have initiated copyright infringement lawsuits targeting AI music firms like Suno and Udio. These cases allege that the AI companies trained their models on copyrighted sound recordings without permission, seeking substantial damages on the basis that this activity constitutes widespread unlicensed copying outside the scope of fair use. The AI companies counter that such use qualifies as fair use or intermediate processing, permitted under certain US laws, and argue that record labels are trying to monopolise the market and stifle innovation. Evidence submitted by record labels has pointed to AI-generated songs bearing striking similarity, even near-identicality, to copyrighted tracks.

In response to these challenges, some musicians have adopted technical measures to disrupt AI training efforts. One approach involves embedding subtle and inaudible modifications into recordings that do not affect human listeners but confuse AI models attempting to learn from them. American electronic musician Benn Jordan, also known as The Flashbulb, advocates for this method through a tool called “Poisonify.” Industry groups are also calling for greater transparency from AI developers about their training datasets and for the creation of licensing frameworks to ensure creators receive fair compensation, potentially extending traditional music licensing models—including performance, mechanical, synchronisation, and communication licences—into the AI era.

A distinct yet related legal issue concerns the copyright status of AI-generated content itself. Since AI lacks human authorship, works produced solely by AI may fall outside the scope of copyright law, affecting the commercial value and protection of such creations. The widespread adoption of cost-effective AI-generated content raises questions about the future role and sustainability of human musicians.

Throughout the 21st century, musicians have navigated significant challenges, including the advent of peer-to-peer file sharing platforms such as Napster and Pirate Bay, the rise of streaming services, and ongoing struggles over royalty fairness. The emergence of AI in creative domains represents the latest and arguably most complex battleground for artists seeking to protect their rights and livelihoods amid rapid technological change.

The information discussed is drawn from an analysis published by Mondaq and intends to provide an overview without offering legal advice. Musicians and stakeholders facing specific concerns are advised to seek specialised counsel tailored to their individual circumstances.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PvofqJoyT_c – Documents the silent album protest by over 1,000 British musicians including Kate Bush and Annie Lennox against UK government AI copyright proposals.

- https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/musicians-silent-album-protest-ai-plans/ – Details the release of ‘Is This What We Want?’ album and list of participating artists including Max Richter and The King’s Singers protesting unauthorized AI training.

- https://www.4ca.com.au/trending/music/the-war-on-ai-music-how-artists-are-taking-a-stand/ – Covers lawsuits by Universal Music Group and Sony against AI platforms Suno/Udio, and Anthropic’s settlement over AI-generated lyrics.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PvofqJoyT_c – Includes Ed Newton-Rex’s explanation of how proposed UK law changes could allow AI companies to use creators’ work without compensation.

- https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/musicians-silent-album-protest-ai-plans/ – Confirms the album’s track titles spell a protest message against legalizing ‘music theft’ for AI training purposes.

- https://www.4ca.com.au/trending/music/the-war-on-ai-music-how-artists-are-taking-a-stand/ – Discusses technical countermeasures like Benn Jordan’s ‘Poisonify’ tool to disrupt AI training processes.

- https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMihgFBVV95cUxQODZfRzVOTl9VbG1oWFVWVERxSFNhRDVVdVdnUFowX04ySnNFQ2d5NzhQNVNVVFlPVFNtaHgwNlgtWmd2S3hUdWhWSHNjTzRZbUI4NUY1a3RST0dVZTRlQnRwM2ZxM2ktR012QzhwSHo2WDBoeEhDWnMxRFd1YmNNbGJyV2JXZw?oc=5&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en – Please view link – unable to able to access data

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative discusses recent protests and legal challenges related to AI and music, indicating current relevance. However, specific legislative and legal developments could imply that some information is based on recent events, though detailed timelines are not provided.

Quotes check

Score:

5

Notes:

There are no direct quotes provided in the narrative. Without specific quotes to verify, it’s difficult to assess originality or sources.

Source reliability

Score:

6

Notes:

The information is drawn from an analysis by Mondaq, which suggests a level of credibility. However, the lack of direct citation from primary sources and the absence of well-known media outlets (e.g., Financial Times, BBC) limits the confidence in its reliability.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The claims about musicians protesting the use of their music in AI training and the legal challenges related to copyright are plausible and align with ongoing technological and legal debates. The narrative also highlights practical responses by musicians, such as using tools like ‘Poisonify’, which add to its credibility.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative is generally plausible, discussing current and relevant issues related to AI and music copyright. However, the lack of specific quotes and the reliance on secondary analysis limit the confidence in its overall reliability.