As climate impacts intensify and debt burdens tighten, low-income nations struggle to progress economically while transitioning to clean energy, hindered by limited financial support and restrictive global trade and technology policies.

Climate change, debt, and development present an intricate and intertwined challenge that severely affects low-income countries’ prospects for economic justice and national progress. These nations, burdened by heavy debts and facing escalating costs linked to climate change impacts, are often caught in a cycle that hinder their ability to advance economically while transitioning away from fossil fuels.

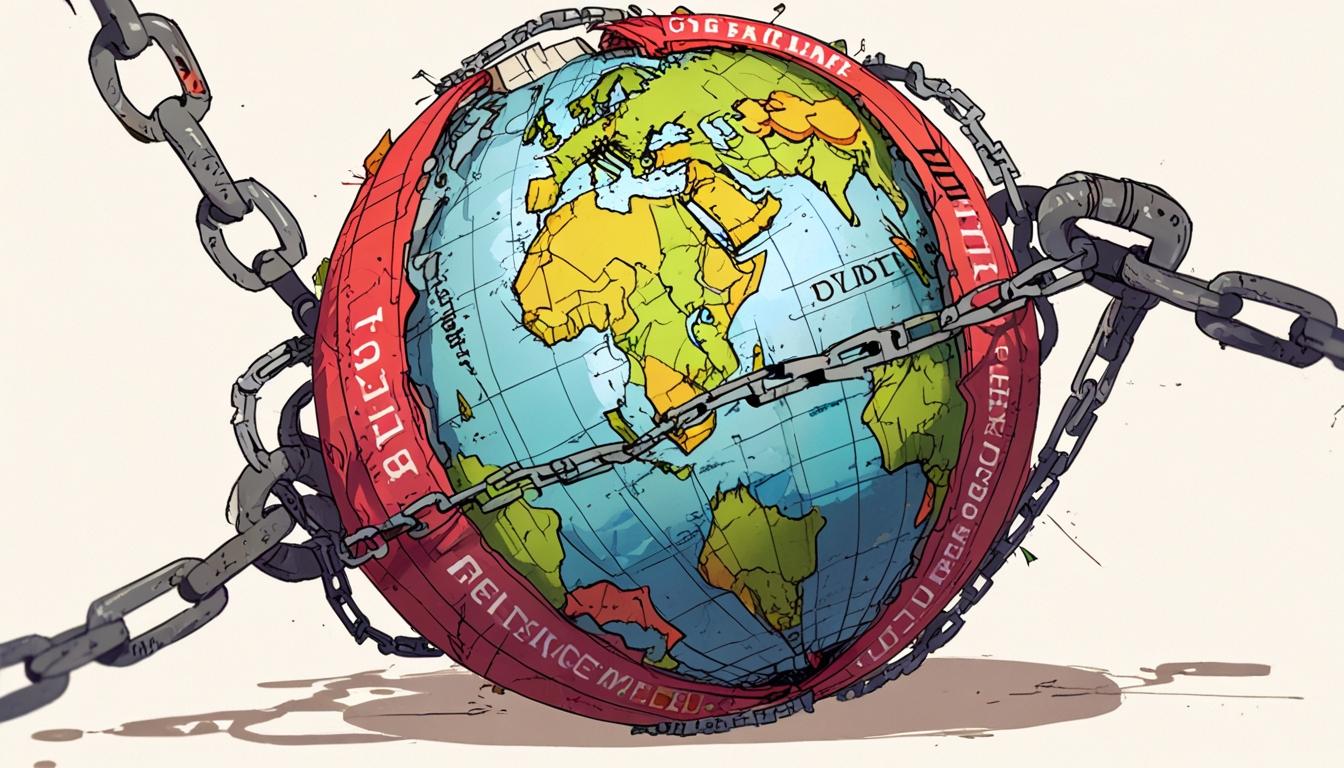

This complex issue, resembling a terrestrial “three-body problem” involving debt, development, and climate change, creates unpredictable and compounding crises for poorer nations. The wealthy world’s primary response has focused on global carbon emission reductions, driven by their own energy transitions away from fossil fuels. However, the solutions offered often fall short of addressing the core issues for poorer countries, particularly because their involvement in emissions is relatively minor compared to wealthier nations.

International efforts such as “debt-for-climate” swaps, designed to reduce emissions and debt simultaneously, have largely been limited in scope and scale, offering only modest relief for countries grappling with climate-related challenges. Furthermore, while some low-income countries hold valuable deposits of critical minerals like lithium, nickel, and cobalt essential for the clean energy shift, they remain confined largely to raw material extraction, restricting economic gains from moving higher up the value chain. Wealthier nations continue to restrain technology transfer and impose trade and intellectual property rules that inhibit these countries’ industrial growth.

As a result, many low-income countries find themselves trapped in a difficult position: unable to break into the clean energy economy beyond raw material supply and simultaneously restricted in their use of fossil fuels, which hampers traditional economic development pathways. The burden of debt servicing combined with escalating climate costs, such as flooding and extreme weather events, deepens their vulnerability.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres highlighted in June 2024 the need for wealthier countries, described as “the godfathers of the climate chaos,” to contribute financially by imposing a “windfall tax” on fossil fuel companies’ profits to help finance climate solutions. The approach targets large profits generated by oil, gas, and coal companies to fund climate initiatives, although it does not directly curb fossil fuel production and might risk incentivising increased extraction to maintain profits.

Besides taxation proposals, a range of financial instruments and initiatives have been explored. One such measure is the distribution of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which provides low- and middle-income countries with funds that can be used for various purposes, including climate adaptation and debt repayment. The IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) aims to offer concessional financing for climate-related resilience, but it still increases debt burdens since funds are dispensed as loans.

Moreover, the newly established Loss and Damage Fund, created at the 2023 COP in Dubai, seeks to provide grants to vulnerable countries impacted by climate change, thus avoiding adding to their debt. However, the fund’s financial resources, at $765 million as of March 2025, fall considerably short of the needs, exemplified by the $16 billion required by Pakistan alone following severe floods in 2022. The fund’s administration through the World Bank has stirred controversy due to the institution’s historical role in driving financial burdens on developing countries.

Climate financing commitments made in 2009, which aimed to mobilise $100 billion annually by 2020, reached $116 billion in 2022, but this sum is dwarfed by estimates suggesting a need for $2.4 trillion per year. Additionally, a significant portion of climate finance comes in the form of loans rather than grants, deepening the debt challenge.

Countries vulnerable to climate change are increasingly facing fiscal crises, as reported by African Business in March 2025, which noted that almost 60% of such developing economies are at high risk. African leaders, including former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, have called urgently for debt relief, highlighting the severity of the current crisis.

Some low-income countries have pursued alternative strategies to improve their economic standing amid these difficulties. Indonesia, for example, a major coal user and the world’s largest nickel producer, has sought to add value domestically by banning raw nickel exports and investing in processing capacity with foreign capital. This strategy aims to move beyond raw material exports to producing higher-value clean energy components like lithium-ion batteries. However, these efforts face international trade disputes, such as an EU challenge at the World Trade Organization, and global market forces that have depressed nickel prices.

Other nations with critical minerals, such as Argentina with lithium and Chile with copper, are exploring similar approaches. These moves reflect attempts at “resource nationalism” that seek to retain more value from natural resources despite international resistance and environmental concerns regarding mining impacts.

In addition to state-level strategies, grassroots and community initiatives offer alternative visions, such as Ecuador’s 2023 referendum to preserve oil reserves in Yasuní National Park, opposing fossil fuel extraction. Movements advocating “buen vivir” promote sustainable lifestyles and challenge conventional growth and energy consumption models prevalent in rich countries as well as in poorer ones.

Financial remittances from migrant workers, amounting to nearly $860 billion in 2023, represent a significant resource that surpasses funding by global financial institutions. Ideas to leverage these funds for sustainable development, such as establishing green reconstruction funds that promote climate-friendly investment while avoiding debt, have been suggested as bottom-up approaches to energy transition.

Debt cancellation remains a fundamental element discussed in efforts to resolve the debt, development, and climate nexus. Historical precedents, like the 1953 London Debt Agreement for West Germany, offer valuable lessons in how debt relief combined with investment can support national rebuilding and economic strength, framed then as a geopolitical strategy against communism. Today, this approach could be reframed to position low-income countries as key defenders in the global fight against climate change.

The complex relationship among climate change, debt burden, and development underscores the critical necessity for coordinated and innovative solutions that address these intertwined challenges. While various international proposals and financial instruments exist, their current scale and implementation often fall short, leaving many vulnerable nations in precarious economic and environmental conditions. The discourse continues to evolve around striking a balance between effective climate action, economic development, and financial sustainability for the world’s poorest countries.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.energymonitor.ai/finance/are-debt-for-climate-swaps-finally-taking-off/ – This article discusses the challenges and limitations of debt-for-climate swaps, including complex governance structures and high transaction costs, which have hindered their widespread adoption.

- https://www.ft.com/content/0bbbe7c7-12a1-43ba-8bef-c5c546367a0e – This piece highlights Indonesia’s emergence as a dominant force in the global nickel market, detailing its export ban and the resulting investments from Chinese companies, which have transformed areas like Bahodopi into major nickel processing hubs.

- https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/lme-brand-approval-cements-indonesian-nickel-ascendancy-2024-05-29/ – This article reports on the London Metal Exchange’s approval of Indonesia’s refined nickel brand, marking a significant shift in the global nickel industry and underscoring Indonesia’s growing market power.

- https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/debt-for-nature-swaps-could-give-100-billion-boost-climate-fight-says-report-2024-04-15/ – This report discusses the potential of debt-for-nature swaps to generate up to $100 billion to aid in the battle against climate change, emphasizing their potential in countries facing both debt crises and severe climate threats.

- https://www.ft.com/content/98bfb674-03d9-4b1f-9e02-024aedd2b208 – This article addresses the growing call for reforming sovereign debt relief to address both fiscal and environmental challenges in low-income countries, advocating for ‘greening’ debt restructurings to support climate and nature-positive investments.

- https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2022/162/article-A001-en.xml – This IMF working paper analyzes the economic case for debt-climate swaps, discussing their narrow applicability and the conditions under which they might be more efficient than alternative forms of climate financing.

- https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMi4gFBVV95cUxNYkVteXZvaTFGOHZILTZDZGZFS2VyaXFmU21qM2NZRTdaRWYxX3lWYXhnTlpmdDAwNXF3VWc3aFJoVEFjYmtXSF9halZ6SmhiaTBkWFlpVXl2b1lVdGU3OUZwMF9UWDJ1S1JjR2NrMmt6SFFpdmRtSVdKS3A4SWdjbGgzeUhyN1dEMlVHUTRZUmJjUkpremd3YjBWNUotWlJ2UXJuOUZsbUJRcGFsQ0JCWjhwQjFueXFJaWQxT2ZfZHRhMDFxRk5qLUtrbGFaaFc2QjNlYWJ4b3p6UUFoRGprUEN3?oc=5&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en – Please view link – unable to able to access data

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative includes recent events, such as the 2023 COP in Dubai and mentions of UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ comments from June 2024, indicating it is relatively up to date, although the issue itself is ongoing and involves historical challenges.

Quotes check

Score:

6

Notes:

No direct quotes are explicitly identified in the narrative, but it refers to UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ call for a ‘windfall tax.’ However, no earliest known reference or original source for this specific quote was found, although his stance on climate action is well-documented.

Source reliability

Score:

5

Notes:

The narrative does not specify its origin from a well-known reputable publication. It discusses complex issues using global perspectives and data points, suggesting a structured approach but without clear attribution to a trusted source.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative aligns well with known challenges and discussions surrounding climate change, debt, and development. The issues described, such as the debt-for-climate swaps and the role of critical minerals, are plausible and supported by current global trends.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative addresses timely and significant global issues, incorporating recent events and well-documented challenges. While it presents a plausible analysis, the lack of specific source attribution and direct quotes reduces confidence in its overall reliability.