Clearsprings, Serco and Mears have profited nearly £150 per minute from UK asylum accommodation contracts, raising concern amid reports of poor living conditions and a surge in refugee arrivals. Campaigners demand urgent government action to reassess these lucrative arrangements.

Private companies managing asylum seeker accommodations in the UK have come under scrutiny for their enormous profits amidst a growing crisis in refugee housing. Over the past five years, three firms—Clearsprings, Serco, and Mears—have collectively made £380 million. This staggering figure, equating to roughly £146 of profit every minute, has raised serious concerns about the quality of accommodation provided to thousands of asylum seekers, particularly as the number of individuals arriving in the UK by small boats surpasses 11,000 in just the current year.

According to a recent National Audit Office report, the companies have established a seven per cent profit margin from their Home Office contracts, which started in September 2019. These contracts involve not only housing seekers in hotels but also managing various forms of temporary accommodation that critics argue are often overpriced and inadequate. Campaign groups have advocated for an end to what they describe as the “privateering” of essential services, emphasising the urgent need for reassessment of these lucrative contracts, which are set to run until at least 2029.

As of December 2023, about 42,000 asylum seekers were residing in what the Home Office describes as “contingency accommodation,” with the majority housed in hotels. This type of arrangement appears to be more profitable for the contractors compared to other forms of accommodation. This financial incentive, however, raises ethical questions, particularly when placed against the contrasting backdrop of the poor living conditions reported by asylum seekers in some of these facilities.

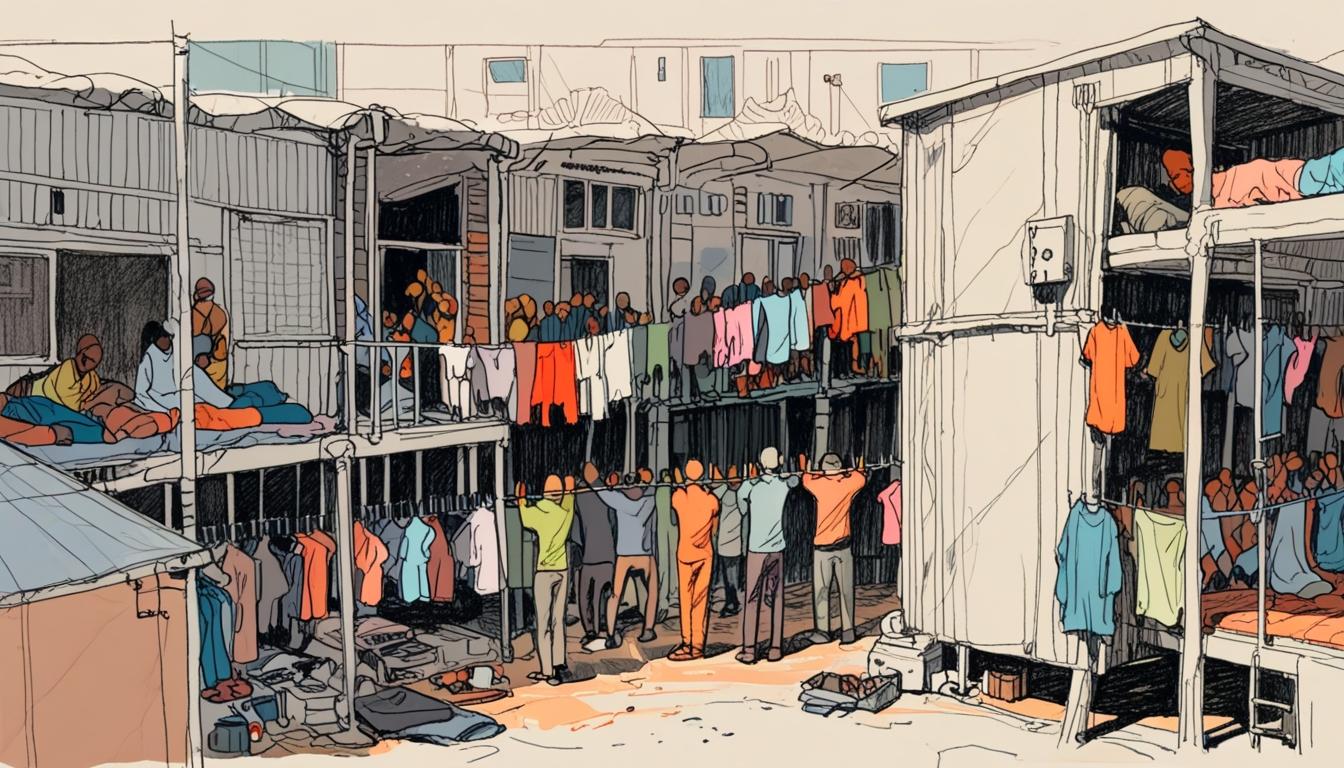

Graham King, founder of Clearsprings, epitomises the controversial relationship between private profit and public service. His company reportedly generates a daily profit of £4.8 million from its asylum contracts, leading him to feature on the Sunday Times Rich List with an estimated net worth of £750 million. Critics argue that King’s substantial earnings come at the expense of asylum seekers, who have described their living conditions as “decrepit” and “impoverished.” Evidence presented to Parliament highlighted alarming situations where multiple individuals were housed together in cramped, unsuitable conditions, leaving many suffering from significant mental distress.

Another substantial player, Mears Group, has also enjoyed soaring profits from its Home Office contract, with reported pre-tax profits jumping to £46.9 million in the latest financial year—an increase of over 83% compared to previous periods. Although the company claims to provide “safe, habitable and fit for purpose” accommodation, reports reveal that its properties often fall short, suffering from issues like bed bugs and inadequate safety measures. Mears has previously insisted on maintaining lower executive salaries compared to industry standards, yet its financial dealings suggest otherwise, with substantial bonuses being awarded to senior employees.

Serco, which manages a contract worth approximately £5.5 billion, has positioned itself as a significant player in the capitalisation of asylum accommodation. Under the leadership of CEO Anthony Kirby, the company reported total revenues of £5.29 billion last year, with a substantial portion derived from its immigration services. Despite facing severe criticism for its management practices—including significant payouts and questionable financial ethics—Serco defends its profits by claiming they represent a minimal return across government contracts.

Emerging criticisms surrounding these firms have prompted renewed calls from politicians and advocacy groups for government oversight. The ethical implications of profiting off vulnerable individuals in desperate circumstances continue to invoke wider debates about the nature of the Home Office’s contracts and their efficacy moving forward.

The escalating financial returns for these firms, juxtaposed with the persistent shortcomings in accommodation quality, underline a troubling reality where profiteering seems to overshadow the fundamental humanitarian needs of asylum seekers. As the situation evolves, the future of these contracts, and by extension the welfare of those seeking refuge, remains a pressing concern for policymakers and the public alike.

Reference Map

- Paragraph 1: 1, 6, 7

- Paragraph 2: 1, 2, 6

- Paragraph 3: 1, 6

- Paragraph 4: 1, 4

- Paragraph 5: 1, 4, 5

- Paragraph 6: 1, 3, 4

- Paragraph 7: 1, 4, 7

- Paragraph 8: 1, 6, 7

- Paragraph 9: 1, 6, 7

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-14691079/The-migrant-hotel-kings-raking-millions-asylum-seekers-Bosses-three-firms-380m-profit-providing-refugee-accommodation.html?ns_mchannel=rss&ns_campaign=1490&ito=1490 – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-essex-67217309 – Clearsprings Ready Homes, a contractor providing accommodation and services for migrants across southern England and Wales, reported a £62 million profit after tax, more than doubling its previous year’s profit of £28 million. The company’s turnover also increased from £502 million in 2022 to nearly £1.3 billion for the year ending 31 January 2023, reflecting the growth in the number of migrants. The company has been previously criticized for offering poor-quality meals to asylum seekers in the hotels.

- https://www.ft.com/content/a9de3d15-140a-44e7-8e0e-9189b69e3bd0 – Clearsprings, a company providing housing for asylum seekers, has seen a significant increase in profits due to high demand for asylum accommodations, with pre-tax profits rising 60% to £119 million. This surge in profitability has drawn the attention of new Labour ministers, who are concerned about the large sums paid to private companies for handling asylum housing, leading to calls for potential renegotiation or termination of contracts in 2026. High demand has been attributed to political and economic turmoil in various countries, causing more asylum applications in the UK.

- https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/content/2d94ebc1-86f6-5a39-a767-f9d3a487d277 – Mears Group, a provider of accommodation services, reported a record pre-tax profit of £34.9 million, more than doubling from £16.3 million the previous year. The company’s revenue reached £960 million, driven by increased volumes in the Asylum Accommodation and Support Contract (AASC). Despite the strong financial performance, Mears has faced criticism regarding the quality of its accommodation services for asylum seekers, with concerns about the condition of properties and the adequacy of support provided.

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1370734/clearsprings-ready-homes-ltd-gross-profit/ – Clearsprings Ready Homes Ltd, a company providing housing for asylum seekers under contract from the UK Home Office, recorded a gross profit of almost £84 million in 2023. This was an increase of approximately £43 million compared to the previous year, indicating significant growth in the company’s financial performance over the past decade.

- https://www.politicshome.com/thehouse/article/asylum-seekers-held-shameful-accommodation-contractors-profit-off-misery – The article discusses the substantial profits made by companies contracted to provide accommodation for asylum seekers in the UK, including Clearsprings, Mears, and Serco. It highlights the disparity between the profits of these companies and the quality of accommodation provided to asylum seekers, raising concerns about the ethics of profiting from vulnerable individuals and the adequacy of government oversight in these contracts.

- https://www.politicshome.com/news/article/private-shareholders-profits-governments-asylum-seeker-accommodation – Private companies contracted to run government-funded accommodation for asylum seekers in the UK have collectively paid £121 million in dividends to shareholders since securing the most recent contracts in 2019. Mears, Serco, and Clearsprings, the three firms awarded contracts to manage the majority of the UK’s asylum seeker accommodation, have also posted collective profits of well over £800 million during this period, raising questions about the allocation of public funds and the effectiveness of these contracts.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative mentions recent figures and ongoing contracts, indicating relatively fresh information. However, it does not provide new or particularly recent developments beyond existing reports.

Quotes check

Score:

5

Notes:

There are no direct quotes in the narrative, making it difficult to verify their origin or accuracy.

Source reliability

Score:

6

Notes:

The narrative originates from a well-known publication, the Daily Mail, which is generally perceived as having a right-leaning bias. This could affect the presentation of information.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The claims about profits and living conditions are plausible given past reports on similar issues. The narrative aligns with ongoing debates about refugee accommodation in the UK.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative appears plausible and aligns with current debates about asylum seeker accommodations in the UK. However, the lack of direct quotes and the narrative’s source bias affect the overall confidence in the information.