The Accademia’s new exhibition ‘Corpi moderni’ explores Renaissance portrayals of the human body, highlighting iconic works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Giorgione while addressing enduring themes of identity, gender, and mortality.

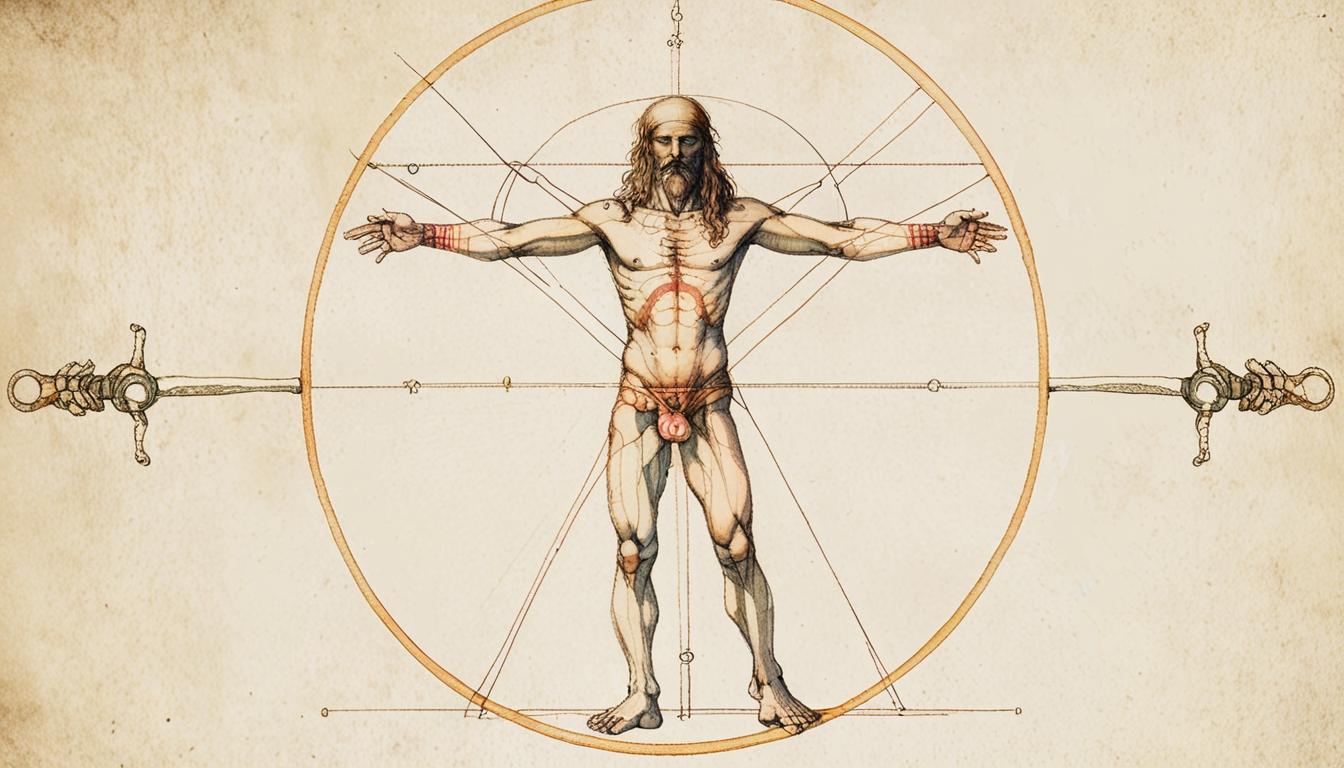

The Accademia in Venice is home to some of the most iconic works of art from the Renaissance, including Giorgione’s enigmatic painting “The Tempest” and Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man”. Both pieces serve as the backbone for the exhibition “Corpi moderni” (“Modern Bodies”), which examines the portrayal of the human body in Renaissance art through diverse lenses—social, aesthetic, and cultural.

This unique exhibition opens with the foremost figures of the Renaissance, showcasing how the body became a focal point for artists as they navigated complex ideas about identity, society, and aesthetics. The first section features masterpieces by Michelangelo, Dürer, and Piero della Francesca—an exploration that culminates in the live presentation of “Vitruvian Man”, a depiction that has transcended time. Originally a mere diagram of proportions illustrating ideal human anatomy, the drawing is transformed here into an artwork of delicate beauty, with Leonardo’s vivacious ink lines and soft watercolours capturing the life and spirit of its subject. This image not only symbolizes humanism but embodies Leonardo’s eternal quest for perfection in art and science.

Moving into the exhibition’s second part, viewers are immersed in the bustling artistic milieu of 16th-century Venice, marked by a confluence of commerce, intellect, and sensory experience. Bellini, Titian, and Giorgione emerge as pivotal figures with their vibrant works entangled in a social fabric woven from literature, fashion, and changing mores regarding gender. This section prompts reflections on natural and social identities. The exhibition boldly claims that the pressing questions of contemporary society began their journey during the Renaissance—a time of profound transformation.

Under the watchful gaze of Antonio Rizzo’s statue “Adam”, the exhibition introduces significant smaller works, including Piero della Francesca’s “Projection of the Human Head”, a geometric study that laid the foundations for understanding perspective. Dürer’s “Self-portrait Nude” also gains particular attention for being the first known nude self-portrait in Western art. The work captures both vulnerability and mastery, contrasting with Dürer’s other notable creation, “An African Man”, marking a pioneering representation of Black identity in European art—a compelling juxtaposition that highlights the multicultural exchanges prevalent in Venice at the time.

An important highlight is the return of Michelangelo’s “Libyan Sibyl,” a grand anatomical study from the Sistine Chapel that exemplifies the fluidity between male and female forms in his work. The drawing, hailed as one of his finest, illustrates a youthful model twisting in contrapposto, showcasing an ideal of strength and beauty that transcends gender norms, as emphasised by contemporary commentator Pietro Aretino.

Androgyny and transgression are recurring motifs, from Liberale da Verona’s “St Sebastian” to Jacopo Colonna’s “Cristo Redentore”, which invites dialogue on gender representation in art—a conversation that resonates today. The exhibition notes the significance of clothing styles, such as the braghesse worn by courtesans, paired with flamboyant footwear that enhanced their stature and challenged traditional gender expectations.

In stark contrast to earlier nudes, which primarily depicted religious figures, the later part of the exhibition demonstrates how Giorgione and Titian embraced sensuality. “The Tempest”, featuring a nude mother and a clothed youth within an atmospheric setting, exemplifies this liberation of the female form from traditional mythological confines. Titian’s “Venus and Adonis”, painted with such fervour that over 30 versions were produced, encapsulates the visual and emotional richness of desire and mortality.

As the exhibition reaches its conclusion, it reflects on the physicality of mortality with works like Bernardino Licinio’s “The Nude”, which offers an unapologetic celebration of the female form and presence. This transition from the vibrancy of youth to the stark reality of aging is poignantly illustrated through Giorgione’s “The Old Woman”, a raw representation that encourages a moment of introspection for viewers.

“Corpi moderni” threads historical significance with contemporary dialogues, allowing visitors to contemplate the echoes of Renaissance ideals within modernity. The Accademia thus becomes a crucible of artistic evolution, inviting us to reassess our perspectives on body, identity, and the enduring questions of existence.

To July 27, gallerieaccademia.it

Reference Map

- Paragraphs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

- Paragraph 1.

- Paragraphs 4, 7, 10.

- Paragraphs 4, 7.

- Paragraph 1.

- Paragraph 2.

- Paragraphs 4, 10.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.ft.com/content/07ccf0eb-4d21-4126-953a-fa1b6967207e – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/mostra-venezia-uomo-vitruviano-corpi-moderni-2025 – The ‘Corpi moderni’ exhibition at Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia, running from April 4 to July 27, 2025, explores the evolution of the human body’s representation in Renaissance Venice. Featuring works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer, Titian, Giorgione, and Giovanni Bellini, the exhibition delves into how the body was perceived as a field of scientific investigation, an object of desire, and a means of self-expression during the Renaissance. Highlights include Leonardo’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ and Giorgione’s ‘The Tempest’.

- https://www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/tempest – Giorgione’s ‘The Tempest’ (c. 1508) is a Renaissance painting housed in Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia. Commissioned by the Venetian noble Gabriele Vendramin, the painting features a mysterious scene with a young soldier and a nursing woman, set against a stormy landscape. The work is notable for its enigmatic iconography and is considered a significant example of early landscape painting in Western art history.

- https://smarthistory.org/giorgione-the-tempest/ – Giorgione’s ‘The Tempest’ (c. 1508) is among the first paintings to be labeled a ‘landscape’ in Western art history. The work features a young soldier and a nursing woman in a stormy setting, with interpretations of its meaning remaining elusive. The painting is notable for its innovative use of oil paint and its role in elevating the status of landscape painting during the early sixteenth century.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitruvian_Man – Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ (c. 1490) is a pen and ink drawing that illustrates the proportions of the human body, based on the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. The drawing is housed in Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia and is rarely displayed due to its fragility. It is considered one of the most iconic images of the Renaissance, symbolizing the blend of art and science during that period.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tempest_(Giorgione) – Giorgione’s ‘The Tempest’ (c. 1508) is a Renaissance painting housed in Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia. Commissioned by the Venetian noble Gabriele Vendramin, the painting features a mysterious scene with a young soldier and a nursing woman, set against a stormy landscape. The work is notable for its enigmatic iconography and is considered a significant example of early landscape painting in Western art history.

- https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/SmartHistory_of_Art/07%3A_Europe_1300_-_1800/7.07%3A_Italy_in_the_16th_century-_High_Renaissance_and_Mannerism_%28II%29 – This article discusses the rise of landscape painting in early sixteenth-century Italy and northern Europe, highlighting Giorgione’s ‘The Tempest’ as one of the first paintings to be labeled a ‘landscape’. The work features a young soldier and a nursing woman in a stormy setting, with interpretations of its meaning remaining elusive. The painting is notable for its innovative use of oil paint and its role in elevating the status of landscape painting during the early sixteenth century.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The article appears recent, focusing on an exhibition that runs until July 27, with no indication of outdated information. However, specific details about the exhibition’s opening date are not provided.

Quotes check

Score:

10

Notes:

There are no direct quotes in the article that need verification.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Financial Times, a well-established and reputable publication.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

Claims about the exhibition are plausible, focusing on historical artworks and their significance, though specific details about the exhibition’s impact or visitor numbers are not provided.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The article is well-researched and originates from a reputable source, with no major red flags in terms of freshness or plausibility. The lack of direct quotes and the focus on historical information further support its reliability.