Chris Moore’s investigative book claims Lord Louis Mountbatten was involved in a paedophile ring linked to the notorious Kincora Boys’ Home, raising questions over alleged cover-ups by British intelligence and the royal family’s role in historic child abuse scandals.

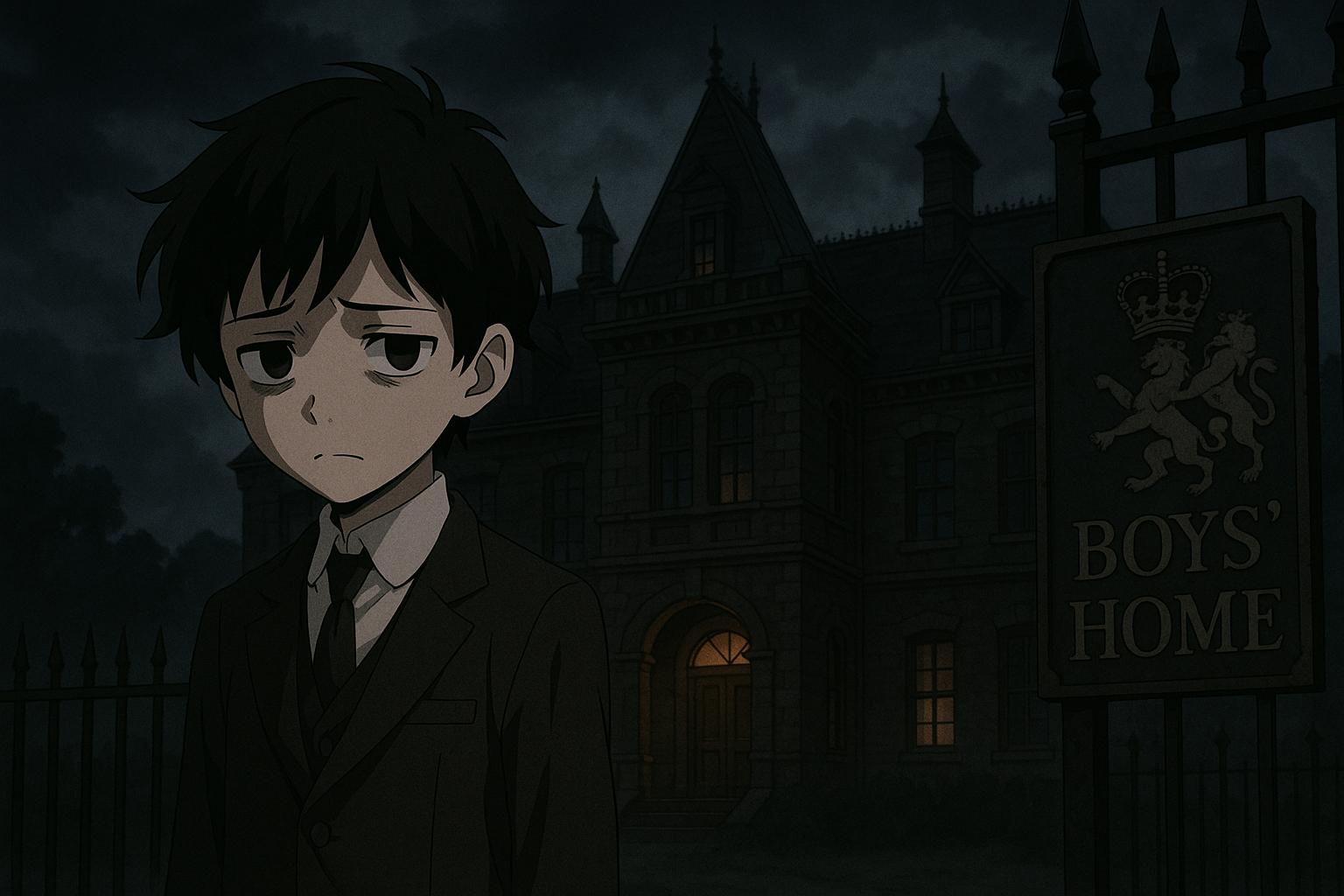

New allegations concerning Lord Louis Mountbatten, a notable figure in British royal history, have surfaced through an investigative book by Chris Moore, which asserts that he was involved in a paedophile ring connected to the infamous Kincora Boys’ Home in Northern Ireland. According to Moore’s publication, Kincora: Britain’s Shame, the deceased royal allegedly abused at least five boys, with some accounts revealing horrific details of their experiences including rape.

The narrative surrounding Mountbatten, who was assassinated by the IRA in 1979, intertwines with longstanding claims of a cover-up involving British intelligence agencies. The book contends that children were trafficked from Kincora, a place notorious for systematic abuse, to Mountbatten’s estate at Mullaghmore, where the alleged abuses took place. This claim raises serious questions about the role intelligence bodies may have played in either facilitating or overlooking such heinous acts. Moore provocatively asks whether these allegations had reached MI5 prior to their publication and whether officialdom is still engaged in protective measures concerning members of the royal family.

The Kincora Boys’ Home, where many of Mountbatten’s alleged victims resided, became a focal point for scandal and outrage following revelations of sexual abuse that first came to light in 1980. Investigations led to the conviction of three staff members, but deeper allegations of state collusion persisted, suggesting that MI5 may have used information from the scandals to further intelligence operations. Amnesty International has labelled the Kincora scandal as one of the most significant of its time, demanding a comprehensive inquiry capable of examining sensitive records that might shed light on the full extent of the abuses and the supposed complicity of state agencies.

Critics of the various inquiries into Kincora maintain that the denial of state collusion is untenable, given the historical context of the Troubles and the intelligence operations during that tumultuous period. Former army information officer Colin Wallace, for instance, has claimed that MI5 and other state entities were not only aware of the abuse but exploited it for their own purposes, using the perpetrators as informants to gather intelligence on loyalist factions. This narrative points toward a disturbing possibility that the protection of the monarchy could have taken precedence over the welfare of vulnerable children.

Amidst this tumult, one former Kincora resident, Arthur Smyth, has recently taken a landmark legal step by suing several Northern Irish state institutions, alleging Mountbatten’s sexual abuse in the 1970s. This legal action marks a noteworthy moment as it challenges the long-held notion of royal immunity from accountability concerning such grave accusations.

In light of the additional evidence and testimonies presented in Moore’s work, the public response has been one of renewed indignation and calls for transparency. Lord Mountbatten’s legacy, once characterised by his close ties to the royal family and military service, is now being overshadowed by these grave allegations. As the inquiry continues, there remains a pressing need for a thorough and unbiased examination of the past, with many demanding that the truth, however uncomfortable, be unearthed.

The impact of these allegations extends beyond historical reflection; they call into question the integrity of institutions that are meant to protect children and the complicity of those in power. As society continues to grapple with the legacy of such abuse, it will be essential to maintain a commitment to seeking justice for victims and holding accountable those who may have shielded abusers under the guise of authority.

Reference Map

- Paragraph 1: [1], [7]

- Paragraph 2: [1], [2], [4]

- Paragraph 3: [3], [2], [4]

- Paragraph 4: [2], [6]

- Paragraph 5: [5], [7]

- Paragraph 6: [1], [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.irishnews.com/news/northern-ireland/lord-louis-mountbatten-abused-children-trafficked-to-his-mullaghmore-estate-C5PL5Z5DHBAQTPUWGVBHQPJTNY/ – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/feb/15/mi5-kincora-childrens-home-northwen-ireland-sexual-abuse – This article discusses allegations that MI5 covered up sexual abuse at Kincora Boys’ Home in Northern Ireland. Victims claim that MI5 blocked police investigations to protect intelligence operations, leading to prolonged abuse. Amnesty International describes the scandal as one of the biggest of its age and calls for a full public inquiry with powers to compel witnesses and access to sensitive documents. The article also highlights the involvement of former army information officer Colin Wallace, who alleges that MI5 was complicit in the abuses and interfered with investigations.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kincora_Boys%27_Home – The Kincora Boys’ Home was a boys’ home in Belfast, Northern Ireland, that became notorious for serious organized child sexual abuse. The abuse first came to public attention in 1980, leading to the conviction of three staff members. Allegations of state collusion emerged, with claims that MI5 and other intelligence agencies were aware of the abuse and may have used it for intelligence purposes. Various inquiries have been conducted, with the 2017 Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry concluding that the abuse was limited to the actions of three staff members and did not involve state collusion.

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/may/30/n-ireland-child-abuse-inquiry-turns-to-kincora-home-and-claims-of-mi5-blackmail – This article reports on the Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry’s examination of Kincora Boys’ Home and allegations of MI5 blackmail. Victims allege that perpetrators were protected because they were state agents spying on fellow Ulster loyalists. The article highlights the involvement of former army intelligence officer Colin Wallace, who claims that MI5, RUC Special Branch, and military intelligence knew about the abuse and used it to blackmail the paedophile ring to spy on hardline loyalists. The inquiry’s chairman, Sir Anthony Hart, has insisted on full access to government and intelligence files related to Kincora.

- https://www.irishtimes.com/crime-law/courts/2022/10/19/mountbatten-accuser-launches-legal-action-against-northern-ireland-state-institutions/ – This article reports on Arthur Smyth, a former resident of Kincora Boys’ Home, who has launched legal action against state institutions in Northern Ireland, alleging that Lord Mountbatten sexually abused him in the 1970s. Smyth is suing the Department of Health, the Secretary of State, the Police Service of Northern Ireland, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, and the Business Services Organisation. The article notes that this is the first time someone has taken legal action against Lord Mountbatten over such allegations.

- https://www.irishnews.com/news/northernirelandnews/2022/10/17/news/former_kincora_resident_claims_he_was_sexually_abused_by_lord_louis_mountbatten-2862939/ – This article reports on a former resident of Kincora Boys’ Home who claims he was sexually abused by Lord Louis Mountbatten. The man alleges that the abuse occurred in 1977 when he was 11 years old. The article notes that this is the first time someone has come forward with such allegations against Lord Mountbatten. The solicitor representing the man emphasizes the importance of exposing perpetrators and institutions that suppressed the truth.

- https://www.irishnews.com/news/northern-ireland/lord-louis-mountbatten-abused-children-trafficked-to-his-mullaghmore-estate-C5PL5Z5DHBAQTPUWGVBHQPJTNY/ – This article reports on fresh claims that Lord Louis Mountbatten was involved in the sexual abuse of children at his Mullaghmore estate in County Sligo. The claims are detailed in a new book by investigative journalist Chris Moore, which alleges that Mountbatten was part of a paedophile ring linked to MI5 and involving children trafficked from Kincora Boys’ Home. The article also mentions previous allegations against Mountbatten, including reports from the FBI and testimonies from former residents of Kincora Boys’ Home.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative mentions recent developments, such as legal actions and an investigative book, which are timely and relevant. However, the underlying allegations refer to historical events, which do not necessarily detract from the freshness but indicate a mixture of new and old information.

Quotes check

Score:

6

Notes:

There are no direct quotes from primary sources that could be verified. The text does include quotes from Chris Moore’s book, but without specific references to earlier publications or interviews to confirm originality.

Source reliability

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative originates from a reputable publication, The Irish News, which lends credibility. However, the sources referenced within the text include both established news outlets like The Guardian and less detailed sources like Wikipedia.

Plausability check

Score:

5

Notes:

The claims are serious and have been part of ongoing discussions about historical abuse. While the narrative is plausible given the context of the Kincora scandal and allegations of state collusion, the lack of conclusive evidence makes it challenging to fully verify these assertions.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative presents serious allegations against Lord Louis Mountbatten, supported by recent legal actions and an investigative book. However, the historical nature of the claims and lack of direct quotes or definitive evidence leave many questions unanswered. The reliability of the source and the plausibility of the claims are moderate, warranting further investigation.