The UK government’s decision to reject a proposed amendment requiring AI companies to reveal when they use copyrighted content for training fuels a heated conflict with artists and copyright holders, highlighting tensions between pioneering AI innovation and protecting creators’ rights.

The United Kingdom is navigating a pivotal moment in its approach to the intersection of copyright law and artificial intelligence (AI). Recent developments signal a contentious stance by UK ministers as they look to block an amendment that would require AI firms to disclose when they utilise copyrighted materials in training their models. This move underscores the government’s ambition to establish the UK as a trailblazer in AI innovation but simultaneously raises significant concerns among content creators and copyright holders.

At the core of this debate lies a proposal introduced in December 2024, which seeks to create a notable exception within the copyright framework. This exception would allow generative AI companies to train their models on a wide array of internet content without obtaining prior consent from the original creators. Such a shift represents a radical departure from traditional copyright practices and has ignited fierce discourse regarding the rights of content creators. According to the government’s consultation document, the initiative aims to strike a balance between enabling the development of “world-leading AI models” and safeguarding the rights of content holders, offering an opt-out mechanism for creators who wish to retain control over their works.

However, the reaction from the creative community has been overwhelmingly negative. Musicians and other artists have articulated their concerns, asserting that the proposal is not only disproportionate but also undermines both UK and international copyright frameworks. The nature of these objections reflects broader fears that the legislation, as proposed, could erode the exclusive rights granted to creators under existing laws, particularly those outlined in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Legal clarity within this complex landscape remains elusive. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has recently issued a response to the government’s consultation, emphasising a need to provide support for AI developers while also striving to uphold the rights of creators. Despite these assurances, legal experts highlight that current exceptions available for AI developers are limited, and the viability of these exceptions for AI training processes is untested in court.

Internationally, the UK’s approach sharply contrasts with that of the European Union, which is moving towards more robust protections for creators’ rights. The UK government’s decision to obstruct the transparency amendment appears to reinforce its prioritisation of AI development over the rights of existing content creators. This regulatory divergence raises concerns about the potential for a fragmented legal framework impacting the creative industries, where creators may find their works increasingly vulnerable to unconsented use.

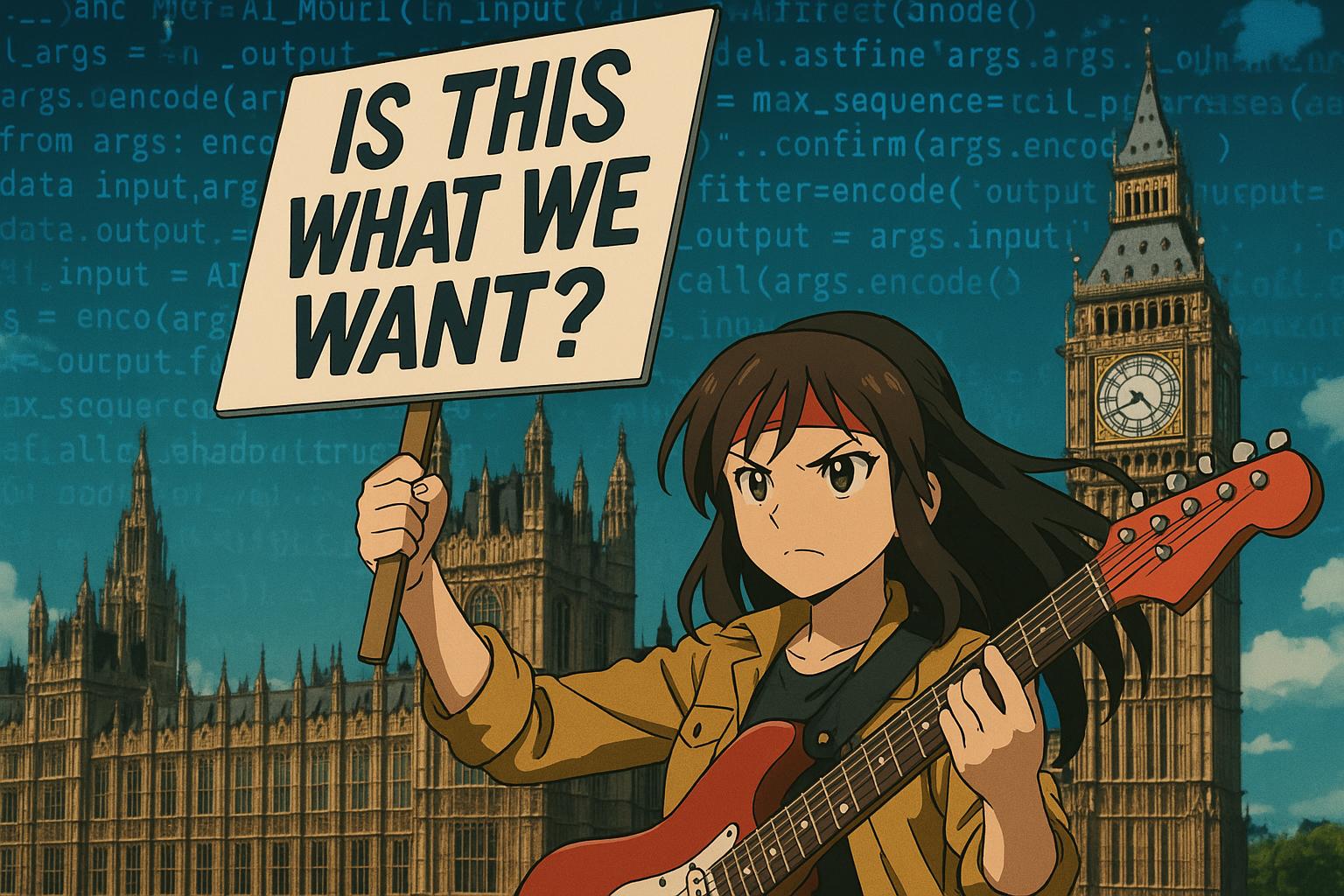

Critics, including a coalition of UK arts and media organisations, have rejected the government’s plans, highlighting that such policies threaten to diminish creators’ livelihoods and undermine the foundational tenets of copyright law. A recent protest from over 1,000 musicians, including prominent figures like Annie Lennox and Kate Bush, further highlights the depth of dissatisfaction. Their silent album, titled ‘Is This What We Want?’, serves as a poignant commentary on the proposed legislative changes.

As the consultation period drew to a close on February 25, 2025, the future of copyright in the realm of AI development hangs in the balance. The upcoming decisions from the UK government will not only shape the landscape for AI technology but also significantly influence the rights and protections afforded to creatives in the UK. The evolving dialogue underscores a crucial tension between fostering innovation and preserving the essential rights of those who contribute to the cultural fabric of society.

With a decisive impasse on the horizon, stakeholders across both industries await the government’s next steps, keenly aware that these decisions could set precedents affecting the balance of power in the creative economy for years to come.

Reference Map

- Paragraph 1: [1]

- Paragraph 2: [1], [2]

- Paragraph 3: [1], [4]

- Paragraph 4: [1], [3], [5]

- Paragraph 5: [1], [4], [6]

- Paragraph 6: [1], [7]

- Paragraph 7: [1], [5]

- Paragraph 8: [1], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.webpronews.com/uk-blocks-bill-requiring-ai-firms-disclose-use-of-copyrighted-material/ – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/dec/17/uk-proposes-letting-tech-firms-use-copyrighted-work-to-train-ai – The UK government has proposed allowing AI companies to use copyrighted material for training models without seeking permission from creators, unless they opt out. This move aims to balance AI development with creators’ rights but has faced criticism from the creative industry, which argues that it undermines existing copyright laws and could harm creators’ livelihoods.

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/dec/19/uk-arts-and-media-reject-plan-to-let-ai-firms-use-copyrighted-material – A coalition of UK arts and media organizations has rejected the government’s proposal to allow AI firms to use copyrighted material for training models without explicit consent. They argue that the plan undermines existing copyright laws and could negatively impact creators’ rights and the creative industry.

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/25/why-are-creatives-fighting-uk-government-ai-proposals-on-copyright – Creative professionals and industries are opposing the UK government’s proposals to allow AI companies to use copyrighted material for training models without explicit consent. They argue that the opt-out system places an unfair burden on creators and could lead to widespread unauthorized use of their work.

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/virginieberger/2025/02/28/how-the-uks-ai-copyright-exception-hands-creators-work-to-big-tech-for-free/ – Over 1,000 musicians, including Annie Lennox, Damon Albarn, and Kate Bush, released a silent album titled ‘Is This What We Want?’ to protest the UK government’s proposed changes to copyright law. The changes would allow AI companies to use copyrighted material for training models without creators’ consent, unless they opt out.

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/11/uk-copyright-law-consultation-fixed-favour-ai-firms-peer-says – A crossbench peer has criticized the UK government’s consultation on AI and copyright law, claiming it is biased in favor of AI firms. The consultation proposes allowing AI companies to use copyrighted material for training models without explicit consent, unless creators opt out, a move that has faced significant opposition from the creative industry.

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/dec/17/uk-proposes-letting-tech-firms-use-copyrighted-work-to-train-ai – The UK government has proposed allowing AI companies to use copyrighted material for training models without seeking permission from creators, unless they opt out. This move aims to balance AI development with creators’ rights but has faced criticism from the creative industry, which argues that it undermines existing copyright laws and could harm creators’ livelihoods.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative references recent developments and consultations, including a proposal from December 2024 and a consultation period ending in February 2025, indicating up-to-date information.

Quotes check

Score:

8

Notes:

No direct quotes are provided in the narrative, which limits the ability to verify their originality.

Source reliability

Score:

6

Notes:

The narrative originates from WebProNews, which is not as widely recognized for its fact-checking as major news outlets like The Guardian or BBC.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The claims about the UK government’s stance on AI and copyright are plausible and align with recent discussions in the technology sector.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative is generally plausible, referencing recent events and policies. However, the reliability of the source could be higher. The lack of direct quotes and the specific details about legal developments make it difficult to fully verify without additional sources.