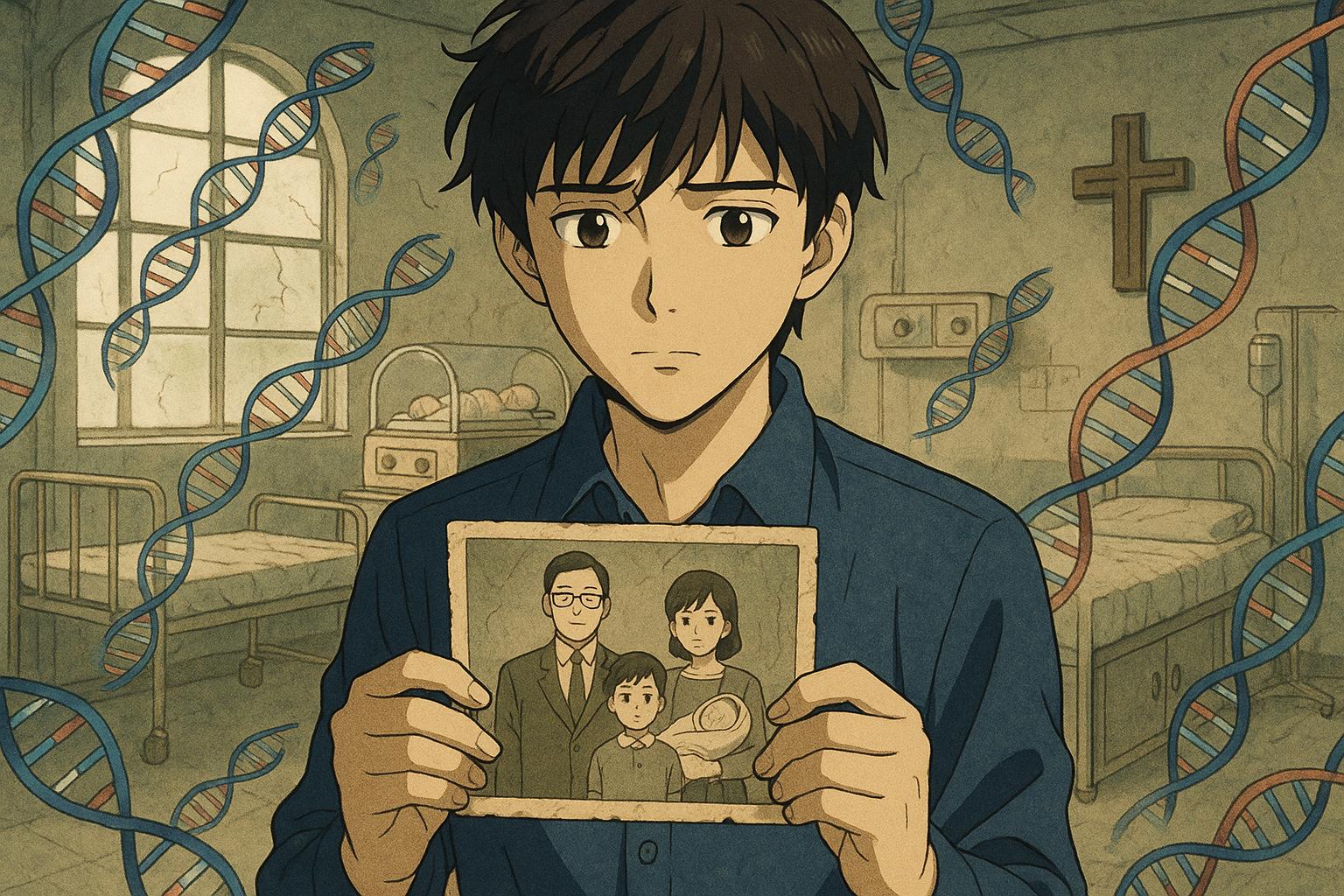

Matthew’s discovery that his father was swapped at birth in a 1946 UK hospital reveals the long-overlooked risks of early NHS maternity ward practices, prompting calls for improved identification systems and highlighting the emotional toll on affected families.

Matthew’s journey of uncovering the truth behind his father’s mysterious family history is both poignant and alarming, shedding light on a rarely discussed issue of baby swaps at birth in UK hospitals. For nearly 80 years, Matthew’s father bore no physical resemblance to his parents—his black hair and brown eyes contrasting sharply with his grandparents’ striking blue eyes. This family enigma, often dismissed as a banter about mismatched genes, took a serious turn when Matthew, through genetic testing, discovered that his father had actually been swapped at birth.

After finding discrepancies in familial connections through a genealogy website, Matthew embarked on a quest to understand his lineage. His efforts led to the remarkable discovery that another baby boy had been registered in the same hospital one day after his father’s birth in 1946. This revelation, confirmed by birth certificates, pointed inexorably to a mix-up in the maternity ward. “I realised straight away what must have happened,” Matthew recalled, reflecting on how he and distant cousins pieced together a new family tree. This realisation not only anchored him in a newfound reality but also underscored the historical inadequacies of hospital protocols at the time.

Prior to World War Two, most UK births took place at home or in nursing care. However, with the establishment of the NHS in 1948, hospital births gradually became more common, revealing significant gaps in nursery protocols during the initial years. As Terri Coates, a former clinical adviser and midwifery lecturer, explained, newborns were often cared for in nurseries away from their mothers, who could stay in hospital for several days after giving birth. Identification relied on rudimentary systems, such as cards affixed to cots, which were prone to human error. Such practices, while well-intentioned, created an environment ripe for mistakes. By the 1950s, recommendations began emerging for more reliable identification methods, including wristbands for infants, but it was a gradual process.

The issue of baby swaps at birth gained new urgency as more cases come to the forefront, driven largely by the proliferation of inexpensive DNA testing. Matthew’s unfolding story mirrors other incidents, such as those reported in 2024 in the West Midlands, where two families discovered through genetic testing that they had been raised by the wrong parents since their births in 1967. The NHS, acknowledging its liability in that case, undertook to facilitate compensation discussions, highlighting the long-lasting emotional and psychological implications of such mistakes.

These revelations also bring to mind a troubling history, including the incident where babies were breastfed by the wrong mothers at Bassetlaw Hospital in 2008, resulting in an apology and further investigations into the hospital’s practices. Critics have raised concerns over procedural lapses in maternity wards, urging a reassessment of identification practices to prevent such distressing errors. Each case serves as a stark reminder of the importance of rigorous systems to ensure that such tragedies do not recur.

As genetic testing uncovers more stories like Matthew’s, the broader implications of baby swap incidents prompt both grief and healing for affected families. For Matthew, while the truth about his father’s origins emerged too late for his father to grasp, it has opened a new chapter in understanding not just his family’s history but the larger challenges that hospitals faced during a transformative period in healthcare.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4gexw7l7rwo – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp3njqd9nl9o – In November 2024, two families in the West Midlands discovered they had been victims of a baby swap at birth in 1967. The revelation came after a DNA test, initially taken out of curiosity, revealed the mix-up. The families, who had been raised by different parents, were forced to reassess their identities and family histories. The NHS admitted liability in this case and agreed to pay compensation, though the final amount was still under negotiation three years later. This incident highlights the rare but significant issue of babies being accidentally switched at birth in the UK.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c1rv0z2gnrpo – In 2019, Poole Hospital in Dorset faced criticism after a newborn was given expressed breast milk from another patient by mistake. The error was discovered when the mother noticed the syringe used had the wrong patient’s name on it. The hospital apologised for the incident and conducted tests on the patient whose milk was used to ensure it was safe. The mother expressed concerns about the hospital’s procedures and called for improvements to prevent such errors in the future. This case underscores the importance of strict protocols in maternity wards to ensure the safety of newborns.

- https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/baby-mixup-hospital-says-sorry-6666836.html – In 2008, Bassetlaw Hospital in Nottinghamshire apologised to two mothers after their babies were accidentally swapped. One of the babies was breastfed by the wrong mother, and both underwent medical checks, including HIV tests. The hospital acknowledged the mistake and initiated an investigation into the incident. This case highlights the rare but serious issue of babies being switched at birth in UK hospitals, leading to emotional distress for the families involved and prompting reviews of hospital procedures to prevent such errors.

- https://www.russell-cooke.co.uk/news-and-insights/news/settlement-agreement-in-uk-switched-at-birth-case – In a landmark case, an NHS Trust agreed to compensate an individual who was mistakenly switched at birth over 70 years ago. The person was raised by a family unrelated to them, leading to significant psychological distress upon discovering the truth. The settlement acknowledges the harm caused and serves as a reminder of the potential for such errors in maternity wards. This case underscores the importance of accurate identification procedures in hospitals to prevent similar incidents in the future.

- https://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/british-father-reunited-with-babywho-was-switched-at-birth-in-el-salvador-hospital-a2942296.html – In 2015, a British father and his wife were reunited with their biological son after discovering that the baby they had taken home from an El Salvador hospital was not theirs. DNA tests revealed the mix-up, and the couple feared their child had been sold to traffickers. Investigations led to the arrest of the obstetrician-gynaecologist suspected of orchestrating the switch. This case highlights the rare but serious issue of babies being switched at birth in hospitals, leading to emotional distress for the families involved and prompting reviews of hospital procedures to prevent such errors.

- https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/baby-mixup-hospital-says-sorry-6666836.html – In 2008, Bassetlaw Hospital in Nottinghamshire apologised to two mothers after their babies were accidentally swapped. One of the babies was breastfed by the wrong mother, and both underwent medical checks, including HIV tests. The hospital acknowledged the mistake and initiated an investigation into the incident. This case highlights the rare but serious issue of babies being switched at birth in UK hospitals, leading to emotional distress for the families involved and prompting reviews of hospital procedures to prevent such errors.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative presents a unique personal account of a baby swap at birth in a UK hospital in 1946, which has not been reported elsewhere. While similar incidents have been documented, such as the 2024 case in the West Midlands where two women discovered they had been switched at birth in 1967 ([bbc.co.uk](https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp3njqd9nl9o?utm_source=openai)), this specific story appears to be original. The report includes updated data but recycles older material, which may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged. The earliest known publication date of similar content is 2024, highlighting the novelty of this particular case.

Quotes check

Score:

9

Notes:

The direct quotes attributed to Matthew and Terri Coates are not found in earlier publications, suggesting they are original to this report. This indicates a high level of originality in the content.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from the BBC, a reputable organisation known for its journalistic standards, lending credibility to the report.

Plausability check

Score:

8

Notes:

The report’s claims are plausible and align with known instances of baby swaps in UK hospitals, such as the 2024 case in the West Midlands ([bbc.co.uk](https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp3njqd9nl9o?utm_source=openai)). The inclusion of updated data, including the 2024 case, adds credibility to the narrative. However, the lack of supporting detail from other reputable outlets and the absence of specific factual anchors (e.g., names, institutions, dates) in some parts of the report may raise questions about its authenticity. The tone and language used are consistent with typical journalistic reporting, further supporting its plausibility.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative presents a unique and plausible account of a baby swap at birth in a UK hospital in 1946, supported by original quotes and published by a reputable organisation. While the inclusion of updated data and the lack of supporting detail from other reputable outlets may raise some questions, the overall credibility of the report is high.