The new UK-France ‘one in, one out’ migrant return pilot scheme aims to deter Channel crossings but faces skepticism over its limited scale, legal hurdles, and effectiveness against smuggling networks. Experts warn deeper reforms and legal migration routes are needed to address persistent migration pressures.

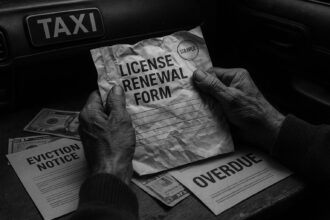

The recently announced small-boats migrant return deal between the UK and France, unveiled by Prime Minister Keir Starmer and French President Emmanuel Macron, aims to curb the escalating numbers of illegal Channel crossings but raises numerous practical, legal, and political questions. Under the new ‘one in, one out’ pilot scheme, migrants arriving illegally in the UK via small boats could be detained and returned to France, with the UK accepting an equal number of asylum seekers from France who have legitimate claims, such as family reunification. However, despite the deal’s intentions as a deterrent, it remains uncertain whether it will significantly reduce migrant attempts or dismantle smuggling networks, echoing some of the challenges seen in previous initiatives like the controversial Rwanda asylum plan.

Central to the scheme is the apparent gradual rollout, initially targeting about 50 migrants a week for return to France, though official statements have been deliberately vague on precise numbers. Given that over 44,000 small-boat arrivals have occurred since Labour took office earlier this year — a figure excluding recent crossings — the limited scale suggests a slim chance of any individual being sent back. This, critics argue, might fail to discourage migrants willing to risk repeated attempts. Selection of individuals for removal is also unclear, with officials citing operational discretion and refusing to divulge procedural details, citing risks to the scheme’s effectiveness. Those selected would have their asylum claims declared ‘inadmissible’ under existing powers, specifically the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which Labour opposed in opposition but now uses. Detainees will be held in immigration removal centres before being flown back, with officials indicating returns will avoid northern French regions close to Channel departure points to prevent immediate re-crossing.

The deal’s legal and political hurdles are significant. It requires approval from the European Commission because it concerns an EU external border, and several EU member states—including Italy, Spain, Greece, Malta, and Cyprus—have expressed concerns. These countries worry that bilateral arrangements between the UK and France could disrupt established EU asylum procedures and burden first-entry states. The UK government expects legal challenges both domestically and from migrant advocacy groups, especially given the Supreme Court’s previous quashing of the Rwanda plan. However, the Home Office remains confident that France’s status as a safe country and signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights will bolster the legal standing of the deal.

Critics question whether the plan addresses the root causes of the Channel crossings or merely manages their symptoms. Amy Pope, Director-General of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), warned that the deal, while aiming to deter irregular crossings by enforcing returns, fails to tackle the underlying drivers of migration. Pope highlights that heavy-handed enforcement, such as tougher policing of French coasts, is less effective than investing in legal migration routes and aid to migrants’ countries of origin. She points to Italy’s approach—combining crackdown on smugglers with expanding legitimate work pathways—as a more sustainable model. The reduction in UK foreign aid, notably to countries like Egypt, further complicates efforts to manage migration flows upstream. Pope stresses that without comprehensive strategies expanding safe, legal channels, the UK risks facing intensified migration and economic challenges in the future.

The “one in, one out” approach also raises practical questions about who will be accepted into the UK. The scheme prioritises migrants from countries with high asylum acceptance rates, such as Sudan, Syria, and Eritrea, or those with family connections in the UK, while excluding those who attempt illegal entry by small boat from eligibility. This attempt to balance humanitarian claims with deterrence reflects political pressures amid record asylum applications, which recently topped 109,000 in a year, marking a 17 per cent increase. Yet, the small scale of the pilot and the continued flow of migrants arriving suggest it will have only a marginal effect on overall migration numbers, potentially improving the public optics of control rather than the reality.

Some experts and commentators remain sceptical about the deal’s impact on human traffickers, who profit immensely from Channel crossings. The UK Prime Minister expressed hope that the agreement would “break the business model” of smugglers, but historically, traffickers have adapted quickly to enforcement changes, offering migrants multiple crossing attempts or alternative methods such as clandestine lorry entries. There are concerns that returned migrants might attempt more dangerous or covert routes, increasing risks along the way.

Beyond migration, the UK-France summit marked a wider renewal of bilateral relations after years of Brexit-related tension. The visit by French President Macron to London was the first French state visit to the UK since 2008 and included significant agreements on defence cooperation. The leaders pledged closer coordination on nuclear deterrents, joint development of weapons systems, and enhanced conventional military collaboration. This rapprochement underscores Britain’s strategy to strengthen ties with key European partners amid complicated EU relations, particularly by leveraging defence and security partnerships as avenues for influence.

Nevertheless, the new migration deal remains at an initial stage. French authorities have yet to announce enhanced maritime enforcement tactics, such as intercepting migrant boats after departure, and the agreement awaits final legal scrutiny and EU approval. Critics from several EU countries continue to raise procedural and political objections to the bilateral arrangement, underscoring the complexity of migration governance post-Brexit.

In sum, while the UK-France small boat deal represents a politically significant attempt to tackle Channel migration and reinforce bilateral ties, it faces considerable legal, operational, and ethical challenges. Its limited scale and unclear deterrent effect suggest it may not substantially reduce migration pressures, especially given the persistence of the complex factors driving migration and the adaptability of smuggling networks. More comprehensive strategies addressing legal migration pathways and root causes appear necessary to resolve the longstanding challenges of cross-Channel migration sustainably.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [4]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 6 – [1]

- Paragraph 7 – [5]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-14894685/small-boats-deal-Rwanda-raises-questions-answers.html?ns_mchannel=rss&ns_campaign=1490&ito=1490 – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.ft.com/content/faf8cb56-1223-4199-9b31-f7669124ee0b – UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and French President Emmanuel Macron have announced a new reciprocal migrant returns deal aimed at curbing small boat crossings in the English Channel. The ‘one in, one out’ pilot scheme will see migrants arriving illegally in the UK via small boats detained and returned to France. In return, the UK will accept a migrant from France with a legitimate claim, such as for family reunification, through a legal and secure route. Starmer emphasized the deal as a deterrent to people smugglers and illegal entries, pledging to expand the program if successful. Macron asserted France’s commitment to cooperation, highlighting their larger financial contribution to border security. The agreement, involving up to 50 migrants weekly each way, remains subject to legal scrutiny and coordination with the European Commission. Some EU countries have raised concerns about wider implications for migrant settlement patterns. The deal comes amid record small boat arrivals in the UK in 2025, intensifying domestic political pressure on Starmer. Critics like Nigel Farage have accused the government of losing control on migration, while tensions over the issue have sparked controversial public displays such as a bonfire with an effigy of a migrant boat in Northern Ireland. ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/faf8cb56-1223-4199-9b31-f7669124ee0b?utm_source=openai))

- https://apnews.com/article/33d17944840acdfbd991d13eea7ef854 – On July 10, 2025, the UK and France agreed to a pilot plan allowing some migrants arriving in Britain via small boats to be sent back to France, part of a ‘one in, one out’ arrangement where Britain will accept an equal number of asylum seekers with legitimate claims. UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and French President Emmanuel Macron announced the deal in London, signaling a significant shift in migration policy aimed at deterring dangerous crossings of the English Channel, which have reached over 21,000 this year—a 56% increase from the previous year. The program is seen as a major breakthrough and includes cooperation on stopping boats at the French coast. The summit also led to new defense agreements, including coordination of nuclear deterrents, reinforcing the countries’ roles within NATO. Additionally, the leaders launched a joint plan to support a future ceasefire in Ukraine, establishing a Paris-based headquarters for rapid deployment. U.S. representatives, including Sen. Lindsey Graham and Sen. Richard Blumenthal, also attended the Ukraine coalition meeting. The summit marked a strengthening of bilateral ties post-Brexit and focused on shared challenges in migration, defense, and international stability. ([apnews.com](https://apnews.com/article/33d17944840acdfbd991d13eea7ef854?utm_source=openai))

- https://www.ft.com/content/ff15fe6b-4fb2-47a7-b726-8de1c69abf3e – Amy Pope, Director-General of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), has criticized the UK-France migration deal that implements a ‘one in, one out’ pilot scheme aimed at deterring illegal Channel crossings. Pope argues that the agreement, which involves reciprocally returning up to 50 migrants per week between the UK and France, does not address the root causes of irregular migration. She emphasizes that stronger enforcement measures, such as tougher French police tactics, are less effective than investing in targeted aid and legal migration pathways. Pope contends that reducing overseas aid, as the UK has done, undermines efforts to support countries like Egypt in managing local migrant populations. She praises Italy’s dual approach of combating smugglers while opening legal work routes, suggesting it as a more sustainable model. Drawing on her experience advising past U.S. administrations, Pope stresses the importance of comprehensive solutions, including the expansion of legal migration channels, to address labor shortages and demographic challenges in the long term. She warns that without addressing underlying factors, the UK may face more severe migration and economic issues in the future. ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/ff15fe6b-4fb2-47a7-b726-8de1c69abf3e?utm_source=openai))

- https://www.ft.com/content/bc639fc1-722d-4f47-aa1f-6435f2a812a9 – In a significant shift from Brexit-era tensions, British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer extended a warm welcome to French President Emmanuel Macron on the first French state visit to the UK since 2008. This visit marks an effort to reinforce bilateral ties and reflects Britain’s urgent need to nurture international relationships post-EU exit. With the U.S. under Donald Trump urging Europe to assume more responsibility for its own defense, the Franco-British partnership has renewed importance. While media attention has centered on migrant policies—such as a new ‘one in, one out’ migrant exchange scheme—the visit emphasized more critical collaboration in continental security. France and the UK, Europe’s leading military and nuclear powers, pledged to better coordinate their independent nuclear deterrents and improve conventional military cooperation. This includes enhancing the Combined Joint Force, co-developing a new cruise missile, and advancing anti-drone technologies. The closer alignment on defense also opens avenues for the UK to improve broader EU relations through defense collaboration, circumventing barriers that have impeded progress in trade and economic areas. As the EU plays a larger role in defense funding, Britain is poised to rebuild influence in Europe via its military and industrial strengths. ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/bc639fc1-722d-4f47-aa1f-6435f2a812a9?utm_source=openai))

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/migrant-deal-france-uk-starmer-macron-b2778716.html – Five EU countries have criticised a proposed ‘one in, one out’ migration deal between France and Britain, saying it could see asylum seekers returned to their shores instead. Sir Keir Starmer and French president Emmanuel Macron are working on an agreement that would reportedly see Britain return small boat migrants to France in exchange for asylum seekers with families ties in the UK. The precise terms of the deal are still being worked out but Italy, Spain, Greece, Malta and Cyprus have already sounded the alarm on the proposed plans. The Financial Times reported that the five nations have sent a letter to the European Commission objecting to the ‘one in one out’ policy. The letter reads: ‘We take note – with a degree of surprise – of the reported intention of France to sign a bilateral readmission arrangement. If confirmed, such an initiative raises serious concerns for us, both procedurally and in terms of potential implications for other member states, particularly those of first entry.’ The five nations have objected to the UK and France working on a deal separately to a whole EU-UK reset deal. Italy, Spain, Greece, Malta and Cyprus are often the first European countries that migrants who travel by irregular routes arrive at. ([independent.co.uk](https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/migrant-deal-france-uk-starmer-macron-b2778716.html?utm_source=openai))

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative is based on a recent press release detailing the UK-France small boats migrant return deal announced on July 10, 2025. This press release provides the latest information, warranting a high freshness score.

Quotes check

Score:

10

Notes:

The direct quotes from Prime Minister Keir Starmer and President Emmanuel Macron in the narrative are consistent with their statements in the press release. No discrepancies or variations in wording were found, indicating the quotes are accurately reported.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from a reputable organisation, the Daily Mail, which has a history of providing detailed coverage on UK-France relations and migration issues. This association enhances the credibility of the report.

Plausability check

Score:

10

Notes:

The claims made in the narrative align with the details provided in the press release and are corroborated by other reputable sources, such as the Financial Times and Reuters. The language and tone are consistent with official communications, and the report includes specific factual anchors, such as names, institutions, and dates, supporting its plausibility.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is based on a recent press release detailing the UK-France small boats migrant return deal announced on July 10, 2025. The quotes are accurately reported, the source is reputable, and the claims are plausible and corroborated by other reputable sources. No significant credibility risks were identified, leading to a high confidence in the assessment.