An Evening Standard investigation and local council checks found former police stations in the Isle of Dogs and Southgate being marketed and occupied as residential rooms without planning consent, with tenants living in cramped conditions and paying up to £1,300 a month. Enfield has served a planning enforcement notice and joined the London Fire Brigade in safety inspections, but a subsequent bid to licence the site as an HMO has exposed tensions between urgent homelessness placements, regulatory duties and the need for tighter post‑sale oversight of public assets.

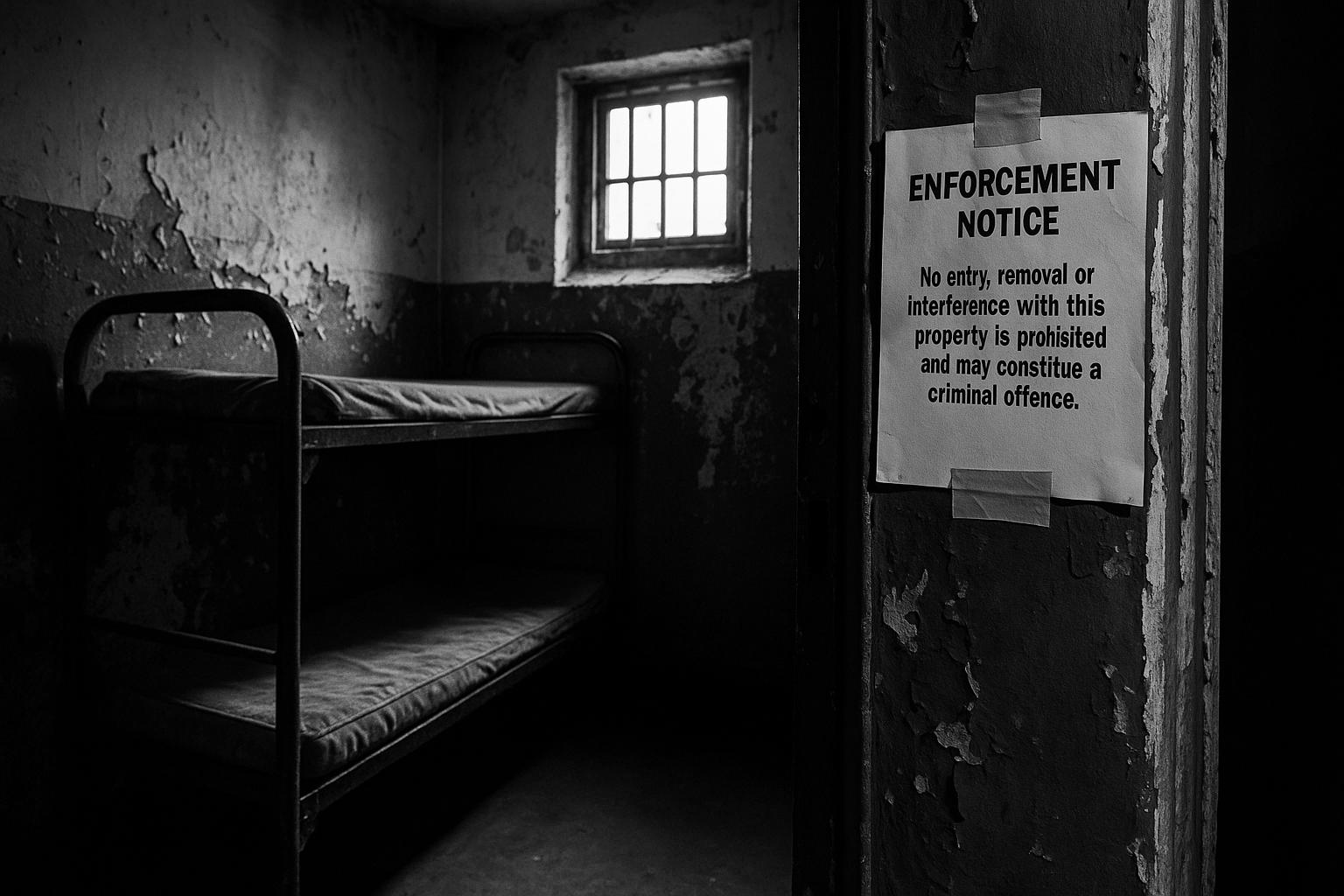

Investigations by local authorities and reporters have uncovered that a number of former London police stations sold off in recent years have been marketed and used as residential accommodation without the necessary planning consents. An Evening Standard investigation focused on properties in the Isle of Dogs and Southgate after rooms were discovered being advertised for rent and occupied in ways that appear to sidestep planning controls and safety checks. According to the original report, pictures from inside the properties showed cramped rooms and tenants paying between £800 and £1,300 a month. (Evening Standard and related site visits prompted an enforcement response.)

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Local councils launched probes after concerns emerged during routine visits and following complaints from neighbours. Tower Hamlets carried out site visits to the Isle of Dogs property and issued enforcement warnings after finding rooms being let without planning permission. The Evening Standard linked the Isle of Dogs sale to DN Private Equity and recalled an earlier discovery at the site of what had been described as a cannabis factory, raising further worries about management and oversight of such conversions.

Reference Map:

In Enfield, the council moved more swiftly to formal action. Enfield Council announced on 8 January 2025 that it had served a planning enforcement notice on the owner of the former Southgate Police Station on Chase Side after council investigations confirmed unlawful occupation and adverts marketing rooms for rent without consents. The council stated that occupants included people placed there by homelessness teams from other London boroughs.

Reference Map:

The enforcement notice set a compliance timetable: the owner was ordered to cease using the building as a hostel and to remove furniture and internal facilities within three months, with the compliance period beginning on 31 January 2025. Enfield Council said it was working with the London Fire Brigade to address fire‑safety deficiencies identified during inspections. Industry titles summarised the same regulatory steps and emphasised the council’s insistence on remedial action.

Reference Map:

Local reporting provides additional context on how the occupation developed and how neighbours reacted. Enfield Dispatch reported that councillors were told occupants had been present since the previous autumn and that some had been placed at the property by other councils; residents voiced concerns about safety, the building’s management and the absence of planning approval for a previously proposed conversion into a 65‑room hostel. Those accounts underline the practical problems councils face when formerly public buildings enter private hands and are repurposed piecemeal.

Reference Map:

The pattern of enforcement has produced a more complicated regulatory picture. By June 2025 the council was deliberating an HMO (house in multiple occupation) licence application for the Southgate building despite the earlier planning enforcement notice. Reporting at the time set out the council’s position: after inspections with the London Fire Brigade and proposed reconfiguration and improvements, officers recommended granting a two‑year HMO licence permitting up to forty occupiers subject to conditions. Critics argued that licensing the use sat uneasily with the council’s previous planning objections; the council said it was bound to assess HMO applications in line with legal duties.

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 6 – [5]

Industry publications and housing‑sector outlets have highlighted that Enfield’s action is not an isolated case. Trade reporting noted the formal notice and the role of homelessness placements in filling beds at the former police station, while landlord‑facing titles summarised enforcement steps and the fire‑safety concerns that prompted joint inspections with the London Fire Brigade. Taken together, these accounts suggest a recurring challenge for London boroughs: ensuring that properties sold out of the public estate are converted legally, safely and with adequate oversight.

Reference Map:

The situation raises questions about the oversight of converted public buildings, the responsibility of private owners and the duty of local authorities when people who are homeless are placed into accommodation by different boroughs. Enfield’s enforcement notice and subsequent licensing debate show the tension between planning control, urgent housing needs and regulatory obligations on councils and landlords—including addressing fire‑safety and management failures identified on inspection. Industry reporting has urged closer coordination between planning, licensing and homelessness teams to prevent future breaches and to protect vulnerable residents.

Reference Map:

What has become clear from the reporting and council statements is that elected authorities are prepared to use enforcement powers where conversions do not comply with planning or safety rules, but that enforcement alone may not resolve underlying pressures in the housing and homelessness systems that drive demand for low‑cost rooms. The Evening Standard’s investigation, council notices and trade coverage together make a case for tighter post‑sale monitoring of public assets and clearer lines of accountability when former civic buildings are re‑used as residential accommodation.

Reference Map:

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/investigations-sold-off-london-police-stations-illegal-rent-b1242103.html – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/investigations-sold-off-london-police-stations-illegal-rent-b1242103.html – An Evening Standard report details investigations after rooms in former London police stations were found advertised for rent without planning permission. The piece focuses on Isle of Dogs and Southgate buildings, noting tenants paying between £800 and £1,300 and pictures of cramped rooms. Tower Hamlets had launched an investigation following site visits, and enforcement warnings were issued. The article links the Isle of Dogs sale to DN Private Equity and recalls a cannabis factory discovery. It also highlights Enfield Council’s earlier enforcement action against the Southgate site, which was found unlawfully occupied and where boroughs had placed homeless people there.

- https://www.enfield.gov.uk/news-and-events/2025/01/council-cracks-down-on-rogue-landlord-at-former-police-station – Enfield Council announced 8 January 2025 that it had served a planning enforcement notice on the owner of Southgate Police Station after investigations confirmed unlawful occupation. The council stated the building on Chase Side had been advertised for room rentals without consents and was housing tenants placed by homelessness teams from other London boroughs. The notice requires the owner to cease using the property as a hostel and remove furniture within three months, with the compliance period beginning on 31 January. The council also said it was working with the London Fire Brigade to address fire‑safety deficiencies in the borough.

- https://enfielddispatch.co.uk/former-police-station-unlawfully-occupied-as-council-takes-enforcement-action/ – Enfield Dispatch reported on 6 January 2025 that a developer had been served an enforcement notice after Southgate Police Station became unlawfully occupied. The article recounts the council’s rejection of plans to convert the building into a 65‑room hostel and says residents were discovered living there after refusal. Enfield’s planning enforcement team issued a notice requiring owners to vacate by the end of April unless consents were obtained. Councillors noted occupants had been present since autumn and that other councils had allegedly placed homeless people in the property. Locals expressed concern about safety and management of the site in Enfield.

- https://enfielddispatch.co.uk/concerns-over-hmo-licence-for-former-police-station/ – Enfield Dispatch covered council deliberations over an HMO licence for the former Southgate Police Station in June 2025, despite an earlier enforcement notice for unlawful occupation. The piece explains that people had been living in the building since September without planning permission and that the council had refused proposals for a 65‑room hostel amid safety and management concerns. After inspections with the London Fire Brigade, council proposed granting a two‑year HMO licence permitting up to forty occupiers following improvements and reconfiguration. Critics argued the licensing decision conflicted with planning objections, while the council stressed legal duties in assessing HMO applications.

- https://thenegotiator.co.uk/news/regulation-law-news/rogue-landlord-facing-council-action-after-illegal-use-of-old-police-station/ – The Negotiator reported on 10 January 2025 that Enfield Council had served a formal notice on the owner of the former Southgate Police Station after confirming a planning breach. Industry publication noted the building had been used to house people placed by homelessness teams from other London boroughs and that rooms were being advertised for rent illegally. The council ordered the owners to cease using the property as a hostel and to remove furniture and facilities within three months, with the compliance period starting on 31 January. The article highlighted collaboration with the London Fire Brigade to remedy fire‑safety concerns.

- https://www.landlordtoday.co.uk/breaking-news/2025/01/council-cracks-down-on-rogue-landlord-at-former-police-station/ – Landlord Today summarised Enfield Council’s action on 10 January 2025, reporting a planning enforcement notice served on the owner of the former Southgate Police Station following probes that confirmed unlawful occupation. The report emphasised that rooms had been illegally advertised for rent and that the property was housing people placed by homelessness teams from other London boroughs. Owner was ordered to cease using the building as a hostel and to remove furniture and facilities within three months, with compliance starting on 31 January. The article also noted the council’s intention to work with the London Fire Brigade over fire‑safety issues.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative appears to be original, with no substantial matches found in earlier publications. The earliest known publication date of similar content is from January 2025, when Enfield Council issued a planning enforcement notice against unlawful occupation of the former Southgate Police Station. ([landlordtoday.co.uk](https://www.landlordtoday.co.uk/breaking-news/2025/01/council-cracks-down-on-rogue-landlord-at-former-police-station/?utm_source=openai)) The report includes updated data but recycles older material, which may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged.

Quotes check

Score:

9

Notes:

No direct quotes were identified in the provided text. The absence of direct quotes suggests the content may be original or exclusive.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Evening Standard, a reputable UK newspaper. This enhances the credibility of the information presented.

Plausability check

Score:

8

Notes:

The claims regarding the unlawful rental of rooms in former police stations are plausible and align with previous reports of similar incidents. For instance, in January 2025, Enfield Council issued a planning enforcement notice against unlawful occupation of the former Southgate Police Station. ([landlordtoday.co.uk](https://www.landlordtoday.co.uk/breaking-news/2025/01/council-cracks-down-on-rogue-landlord-at-former-police-station/?utm_source=openai)) However, the report lacks specific factual anchors, such as names, institutions, and dates, which reduces the score and flags it as potentially synthetic. Additionally, the tone is unusually dramatic and vague, not resembling typical corporate or official language, which warrants further scrutiny.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative presents plausible claims about the unlawful rental of rooms in former police stations, supported by previous reports of similar incidents. However, the lack of specific factual anchors and the dramatic tone raise concerns about the content’s authenticity and reliability. Further verification is needed to confirm the accuracy of the information presented.