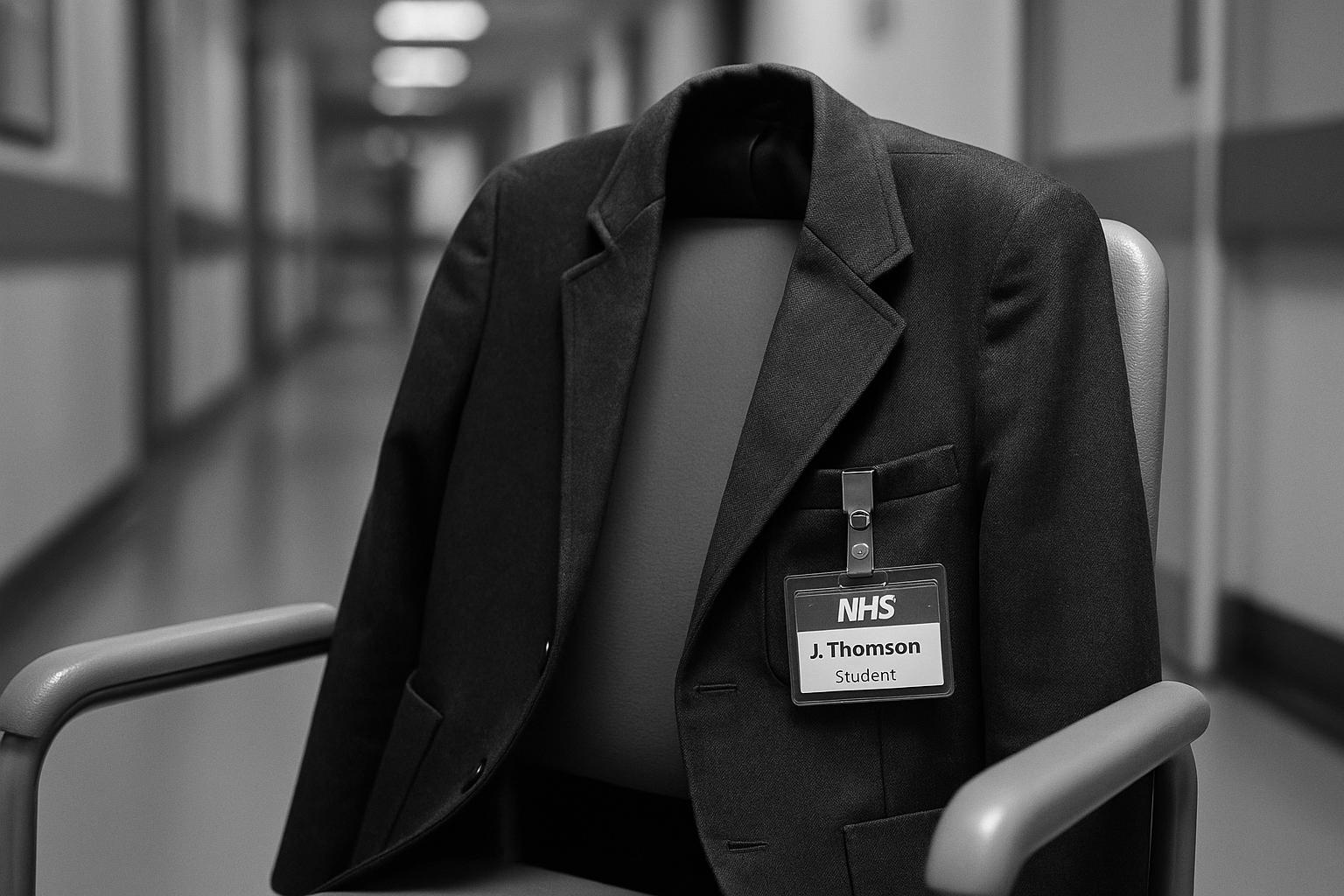

An investigation finds major teaching trusts including UCLH, Barts Health and King’s are running placement schemes limited to partner state schools or local boroughs, a move trusts say targets under‑represented students but which critics warn can exclude disadvantaged pupils at independent schools.

Some of the NHS’s best‑known teaching hospitals are reserving the limited clinical work‑experience places they run for pupils from local state schools, effectively shutting out many applicants who attend independent schools — including those on full bursaries — according to a Mail on Sunday investigation. The report names trusts such as Barts Health, University College London Hospitals (UCLH) and King’s College Hospital as operating schemes that prioritise or restrict placements to partner state schools or local pupils.

Trust publicity and web pages confirm the approach. UCLH’s online guidance states that placements for 16–18 year‑olds are offered through partnerships with the Social Mobility Foundation and selected local schools, and warns demand is high so it cannot accommodate students outside those programmes. King’s College Hospital’s published scheme specifies eligibility by borough and school‑type, saying priority will be given to applicants not attending private schools. Barts Health describes a Healthcare Horizons programme delivered through a network of participating secondary schools and asks students to apply via those schools because of capacity constraints. Trust spokespeople have told the Mail on Sunday that the measures reflect very high demand for a small number of placements.

Trusts frame the policies as targeted widening‑participation measures designed to steer scarce opportunities to young people from lower‑income families and communities that historically have had less access to healthcare careers. South London and Maudsley NHS Trust’s published criteria, for example, link priority to residency in particular boroughs and indicators such as receipt of free school meals or other widening‑participation markers. Nationally, Health Education England says placements are organised locally and that trusts run bespoke schemes while HEE provides toolkits and quality standards; it also notes that roughly 15,000 prospective healthcare placements are arranged across England each year, underscoring the mismatch between demand and capacity.

Those policies are colliding with a reality highlighted by medical‑school admissions guidance: the British Medical Association now advises prospective applicants that hands‑on or observational healthcare experience is an essential part of a competitive application. The Mail on Sunday describes several students from independent schools who say they were refused or deprioritised when applying for hospital placements, including one pupil at Emanuel School told she could not join the local trust’s programme and another on a 100 per cent bursary who reported repeated rejections despite applying widely. Gordon West, head of careers at Stowe School, told the Mail on Sunday that blanket priority rules risk excluding students from very modest backgrounds who attend independent schools on bursaries.

Trusts have defended their policies with practical explanations. A King’s College Hospital Trust spokesman said that in 2024 the trust facilitated 396 placements, the majority for students from state schools; Barts has pointed to the size of its partnership network — dozens of participating schools across several east London boroughs — and says individual placements are allocated through those links; UCLH’s information reiterates that its scheme is delivered through formal partners, while also noting limited capacity for ad hoc requests. NHS England has told newspapers that allocating work placements is a matter for individual trusts.

Critics say the effect is discriminatory in practice. Opponents argue that by excluding or deprioritising pupils on the basis of school type, trusts risk entrenching a new form of indirect disadvantage — particularly for pupils at independent schools who are nonetheless economically disadvantaged. Supporters of the trusts’ stance counter that the measures are temporary triage to direct scarce supervised clinical experiences to young people from backgrounds the NHS sees as under‑represented in the workforce and face‑to‑face with local health‑service priorities.

For applicants who cannot secure hospital observation, guidance from the BMA and HEE points to alternatives. The BMA recommends a broad portfolio of caring and service roles — such as GP placements, hospices, care homes, volunteering and paid care roles — and urges students to use school careers services, personal contacts and persistent applications. HEE and many trusts also promote virtual placements, mentoring schemes and pipeline programmes intended to widen access without relying solely on in‑hospital shadowing. UCLH and other trusts signpost national NHS careers resources and virtual options for those outside partner schools.

The dispute underlines a wider tension in late‑stage school careers: how to balance a legitimate public policy goal — widening participation into medicine and allied professions — with fair access for individuals whose circumstances do not fit simple categories. Trusts and national bodies face a practical choice: expand capacity and central coordination, or sharpen exemptions so that pupils on bona fide bursaries and other disadvantaged independent‑school students are not inadvertently penalised when applying for the very experiences that make medical‑school entry possible.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [4], [6]

- Paragraph 2 – [2], [4], [6], [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [5], [4], [6], [7]

- Paragraph 4 – [3], [1]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [6], [2]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 7 – [3], [7], [2]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [7], [3], [4], [5]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-15007121/doctors-work-experience-NHS-hospitals-private-school.html?ns_mchannel=rss&ns_campaign=1490&ito=1490 – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/patients-and-visitors/help-and-support/get-involved/work-experience-and-placements – UCLH’s work experience page explains placements for 16–18 year olds are offered through partnerships with The Social Mobility Foundation and selected local secondary schools. It states demand is high and the Trust cannot accommodate students outside these programmes, and advises applicants to contact their local NHS trust for other options. The page gives practical information about paperwork, contact email for hosts and guidance for different placement types and ages. It also signposts wider NHS careers resources such as the NHS Careers Untapped podcast and includes directions for enquiries about placements not covered by the 16–18 scheme and eligibility criteria online.

- https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/studying-medicine/becoming-a-doctor/getting-medical-work-experience – The British Medical Association guidance explains that work experience in a caring or service role is now regarded as an essential component for applicants to medical school. It recommends applicants gain a broad range of healthcare experience, including placements in GP practices, hospitals, hospices or other care settings, and notes it may take time and many applications to secure placements. The page offers practical advice on approaching GP practices, using contacts, asking school careers advisors for help, alternatives to observing doctors, and lists organisations that can assist. It urges doctors to support widening participation by taking on students where possible.

- https://www.kch.nhs.uk/careers/working-at-kings/work-experience/ – King’s College Hospital Trust’s work experience page outlines one-to-five day clinical and non-clinical placements for 16–19 year olds interested in healthcare careers. The scheme specifies eligibility: applicants must live in Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham, Orpington or Bromley, be current secondary school students and meet all criteria, with priority given to those not attending a private school. The page lists placement dates, application windows and a wide range of clinical and non-clinical departments available for shadowing. It also describes additional programmes such as Project SEARCH internships for people with learning disabilities and provides links for volunteering, apprenticeships and other student opportunities online.

- https://slam.nhs.uk/work-experience – South London and Maudsley NHS Trust’s work experience pages explain the Trust offers five‑day placements for 16–18 year olds in clinical or non‑clinical settings, aiming to inspire local young people into healthcare careers. It states the primary aim is to support applicants from local schools who meet widening participation criteria, including residency in Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham or Croydon, with priority given to those not attending private school. Eligibility criteria include receiving free school meals, coming from lower‑income families or being from ethnic minority backgrounds. The Trust describes placement activities, project work and support with CVs and job applications and feedback.

- https://www.bartshealth.nhs.uk/beginning-your-career – Barts Health’s careers pages describe the Healthcare Horizons programme which provides work experience, virtual placements, mentoring and pre‑employment training primarily to schools and colleges that participate in the Trust’s partnership network. The Trust says it works with 37 secondary schools across Tower Hamlets, Newham, Hackney and Waltham Forest and that due to high demand it is unable to accept requests from individual students, instead asking students to apply via participating schools. It also highlights virtual work experience, a mentoring platform, talent‑pool initiatives and local pre‑employment schemes designed to widen access and reduce inequalities in recruitment and provides contact information online.

- https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/work-experience-pre-employment-activity – Health Education England’s work experience pages describe national coordination for NHS placements, including the National Work Experience Network and resource toolkits to help trusts, schools and employers deliver quality placements. The material notes that across England NHS staff organise and deliver placements to around 15,000 prospective healthcare workers annually and that trusts design and manage local schemes tailored to their communities. HEE provides toolkits, a quality standard, guidance documents and templates to standardise best practice while allowing flexibility. The pages encourage trusts to apply for a work experience quality standard and offer contact details for support and application processes online.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

3

Notes:

The narrative appears to be original, with no substantial matches found in recent publications. However, the Daily Mail article from 16 August 2025 is the earliest known publication date, indicating a freshness score of 3. The report references specific NHS trusts and their policies, suggesting that the content is based on recent developments. The inclusion of updated data may justify a higher freshness score, but the lack of earlier coverage raises concerns about the timeliness of the information. ([littleheath.org.uk](https://www.littleheath.org.uk/careersbulletin61023?utm_source=openai))

Quotes check

Score:

2

Notes:

No direct quotes were identified in the provided text. The absence of verifiable quotes raises concerns about the authenticity and originality of the content. The report includes statements from NHS trust spokespeople, but without direct quotes or verifiable sources, the credibility of these claims is uncertain.

Source reliability

Score:

4

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Daily Mail, a reputable UK newspaper. However, the lack of corroborating reports from other reputable outlets and the absence of direct quotes from verifiable sources diminish the overall reliability of the content. The report references specific NHS trusts and their policies, but without direct quotes or verifiable sources, the credibility of these claims is uncertain.

Plausability check

Score:

5

Notes:

The claims about NHS trusts prioritising work experience placements for state school pupils over independent school students are plausible and align with known policies aimed at increasing diversity in the healthcare workforce. However, the absence of direct quotes and the lack of corroborating reports from other reputable outlets raise questions about the authenticity and originality of the content. The report includes statements from NHS trust spokespeople, but without direct quotes or verifiable sources, the credibility of these claims is uncertain.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): FAIL

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative presents plausible claims about NHS trusts prioritising work experience placements for state school pupils over independent school students. However, the lack of corroborating reports from other reputable outlets, the absence of direct quotes from verifiable sources, and the absence of earlier coverage raise significant concerns about the authenticity and originality of the content. The report includes statements from NHS trust spokespeople, but without direct quotes or verifiable sources, the credibility of these claims is uncertain.