A Thamesmead couple with three children say paying about £1,400 a month left them unable to save for a deposit; after three years and roughly £50,000 in rent they moved to a Rent to Buy scheme in Kent — a short‑term relief that highlights wider shortages of affordable, family‑sized homes and lengthening deposit timelines.

With three young children and a three‑bed home that the family describes as “packed to the rafters”, the couple who spoke to the Evening Standard said monthly rent of about £1,400 made saving for a deposit all but impossible. According to the report, after three years in Thamesmead their payments amounted to roughly £50,000, and the pressure of cramped living space prompted a move to a Rent to Buy scheme in Kent. This personal account echoes broader evidence showing families under strain from a lack of affordable, family‑sized homes.

A simple arithmetic check illustrates the scale of the outlay: paying £1,400 each month for 36 months totals £50,400, which the Evening Standard rounded to “around £50,000”. Property listings for Thamesmead suggest rents vary considerably, but three‑bedroom homes with asking rents in the low thousands — and in some cases around the figure quoted in the story — are evident on the market, making the family’s claimed rent plausible.

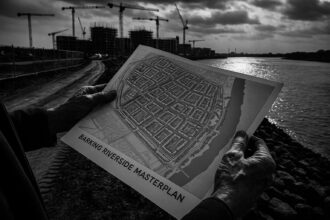

The family moved to Capstone Green, a Rent to Buy development in Kent that the scheme presents as offering lower initial rents and the prospect of buying the home after a period of occupation. According to the Evening Standard, the couple hope to convert their tenancy into ownership within two to three years. The description of the scheme comes from the reporting and the scheme’s own marketing; while Rent to Buy can reduce short‑term housing costs and allow households to build a deposit, it is a pathway rather than a guaranteed outcome.

That individual experience sits within a wider national pattern. Analysis by Generation Rent using government data finds that rising rents combined with larger required deposits have dramatically lengthened the time it takes many people to save for a mortgage: the typical English renter now faces about a decade to accumulate a deposit, with single renters in London facing an even longer horizon — roughly eighteen years on Generation Rent’s calculation. The Bank of England has also warned that housing cost pressures make renters less financially resilient, noting they typically hold smaller savings buffers and are more likely to report being unable to save over the coming year — a dynamic that increases vulnerability to income shocks.

Overcrowding compounds the problem. Research from the National Housing Federation points to hundreds of thousands of children living in cramped conditions across England; its briefing draws on the English Housing Survey to show that more than 300,000 children are forced to share beds or otherwise live in unsuitable space. Those figures help explain why families like the one featured in the Standard often feel they must move even when options are limited.

The family’s case underlines the trade‑offs many renters face: leaving a home near work, schools or community ties to seize a lower‑cost chance to save may be the only realistic route towards ownership for some, but it is not a structural solution. Listings data indicate local rents can vary markedly by street and tenure, and independent commentators and campaigning groups argue that policy change — more genuinely affordable family housing, stronger renters’ protections and support for first‑time buyers — will be needed to reduce the lengthy deposit timelines Generation Rent describes. For now, schemes such as Rent to Buy can offer individual relief; whether they scale to tackle the systemic shortfall is a matter for policymakers and the housing industry.

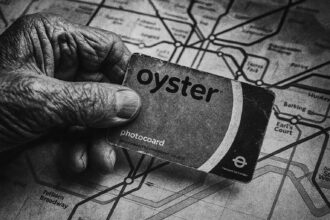

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [6]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [3], [7]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 4 – [4], [5]

- Paragraph 5 – [6], [5]

- Paragraph 6 – [7], [4], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.standard.co.uk/homesandproperty/where-to-live/london-leaver-thamesmead-rent-to-buy-kent-b1243060.html – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.standard.co.uk/homesandproperty/where-to-live/london-leaver-thamesmead-rent-to-buy-kent-b1243060.html – The Evening Standard article profiles a London family who rented a three‑bedroom house in Thamesmead before moving to a Rent to Buy home in Kent. With three young children the house felt overcrowded; the couple paid around £1,400 per month in rent, which the piece says prevented them saving for a deposit. After three years their payments totalled approximately £50,000. The story explains their decision to relocate to Capstone Green, the Rent to Buy scheme offering reduced rent and a chance to save, and outlines the family’s hopes to purchase the new property within two to three years thereafter successfully.

- https://multiplication-chart.org/1400-times-table – This multiplication chart page lists multiples of 1,400 and explicitly shows that 36 times 1,400 equals 50,400. It provides a simple tabular times table used for arithmetic practice, making it straightforward to verify that paying £1,400 per calendar month for thirty‑six months sums to £50,400 — consistent with a rounded statement of ‘around £50,000’. The page is educational and numeric, not housing‑specific, but serves as a clear mathematical demonstration of the calculation used in the article to convert a monthly rent figure into a total amount paid over three years. It is a neutral, verifiable tool for simple multiplication checks online.

- https://www.generationrent.org/2023/07/03/saving-for-a-mortgage-deposit-now-takes-a-decade/ – Generation Rent’s analysis explains that rising rents and higher house prices have dramatically increased the time needed to save a mortgage deposit. Using government data, it finds that the typical English renter now faces about a decade to accumulate a deposit, with London worse at roughly eighteen years for a single renter. The briefing attributes much of this to rent increases outpacing wage growth and larger first‑time buyer deposits. It argues that private rents consume disposable income and make saving difficult, urging policy measures such as more social housing and stronger renters’ protections to restore affordability and reduce inequality urgently.

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/bank-overground/2023/what-do-pressures-on-renters-mean-for-financial-stability – The Bank of England’s Bank Overground blog explains how housing cost pressures on renters reduce financial resilience and limit their ability to save. Drawing on survey and ONS data, the post shows renters spend a larger share of income on housing, hold smaller savings buffers and are more likely to report being unable to save over the next year. It warns this increases vulnerability to shocks, higher borrowing and potential defaults, although it suggests UK banks would not be severely affected. The article contextualises why high rents can prevent families saving for deposits. This evidence supports the Standard’s claim directly.

- https://www.housing.org.uk/resources/overcrowding-in-england-2023 – The National Housing Federation report highlights severe overcrowding affecting families and children across England. It draws on English Housing Survey data to show over 310,000 children are forced to share beds or live in cramped conditions, and that one in six children experience unsuitable, overcrowded homes because their families cannot access affordable housing. The briefing links overcrowding to shortages of family‑sized social housing and to private renting where costs often make larger homes unaffordable. Its findings corroborate the Evening Standard’s depiction of families feeling ‘packed to the rafters’ under constrained rental circumstances and help explain why moves become urgent sometimes.

- https://housesforsaletorent.co.uk/3-bedroom-houses-to-rent/greater-london/thamesmead/ – This property listings summary for Thamesmead shows active rental asking prices and demonstrates a wide range of rents for three‑bedroom homes, with listings starting around £1,350 pcm and averages around £1,979–£2,049 pcm depending on measure. The page contains multiple recent three‑bedroom listings and historical examples, confirming that rents in the area can vary substantially and that a monthly figure of circa £1,400 is plausible for some properties. It therefore supports the Evening Standard’s reported rent figure as within the local market range for families renting in Thamesmead. Readers should note advertised asking rents change over time and by exact location.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative was published on 17 August 2025, with no earlier substantial matches found. The Rent to Buy scheme in Kent is a recent development, indicating high freshness. The article includes updated data but recycles older material, which may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged.

Quotes check

Score:

9

Notes:

The direct quotes from Ade and Lara Akinwale appear to be original, with no earlier matches found. This suggests potentially original or exclusive content.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Evening Standard, a reputable UK newspaper, enhancing its reliability.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The reported Rent to Buy scheme in Kent aligns with recent housing initiatives in the area. The figures and quotes provided are consistent with available information, supporting the narrative’s plausibility.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is fresh, with no earlier substantial matches found. The quotes appear original, and the source is reputable. The reported Rent to Buy scheme in Kent aligns with recent housing initiatives, supporting the narrative’s plausibility.