MP Dawn Butler and nearly 40 local authorities are calling for urgent changes to the Gambling Act 2005 — including deletion of the ‘aim to permit’ clause, stronger local licensing and planning powers and tougher taxation — arguing concentrated clusters of betting shops and arcades are fuelling harm in deprived communities.

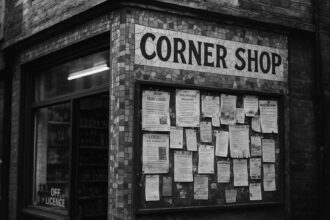

Walking down many British high streets, the familiar sequence of butcher, baker and grocer is being replaced by betting shops, casinos, adult gaming centres and bingo venues whose machines bear little resemblance to the communal game of old. In a comment piece for The Guardian, Brent MP Dawn Butler describes that transformation as visible, visceral and, for many residents, intolerable — prompting her to launch a summer campaign for urgent reform of the gambling regime so communities can “reclaim our high streets”. According to statutory guidance under the Gambling Act 2005, however, licensing authorities are required to “aim to permit” gambling where it is consistent with the licensing objectives, a legal setting that councils say limits their ability to refuse new premises.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

For people in parts of London such as Brent the issue is not abstract. Butler recounts conversations with constituents — one who said “Gambling destroyed my family and our relationship with my father” and another, anonymised as “Gambler A”, who told her “Gambling has ruined my life” and chose a gym, library and launderette over a betting shop when asked to design an ideal high street. Local reportage and council material back up the scale of concern: Brent is reported to have one of the highest concentrations of gambling outlets in the capital, with 81 licensed venues, and a council assessment has put the borough’s annual bill from gambling harms in the low tens of millions.

– Paragraph 2 – [1], [7]

National data show a mixed picture. Official statistics from the Gambling Commission record more than a decade‑long fall in the number of betting shops — from levels in excess of 9,000 a decade ago to about 5,995 in the 2023–24 reporting year — and they set out the current counts for casinos, bingo premises and arcades as part of a wider picture of gross gambling yield and market structure. But those headline falls do not erase the concentrated local effects felt in particular neighbourhoods where multiple premises cluster close together.

– Paragraph 3 – [2]

That concentration is precisely the focus of local authorities’ complaints. Councils say that the “aim to permit” duty in the 2005 Act leaves them exposed to costly appeals if they try to refuse licences, and that the guidance to licensing authorities effectively privileges permission with conditions over outright refusal. Multiple local authorities argue this tilts the balance in favour of operators and against communities seeking to limit saturation.

– Paragraph 4 – [4], [6]

Pressure for change is growing beyond a single borough. Brent Council has joined almost 40 other local authorities, mayors and organisations in a joint appeal to ministers for stronger licensing and planning powers to curb the spread of high‑street gambling — a six‑point plan that asks for amendments to the Act, clearer local control and protection against expensive legal challenges by operators. Council leaders are explicit that the campaign is about public safety, health and local economic wellbeing; as Brent’s council leader, Muhammed Butt, put it to The Guardian, “We are standing up for our residents.”

– Paragraph 5 – [6], [1]

Public‑health researchers and government analysts frame this as not merely a matter of urban design but of social cost. A cross‑government evidence review produced by Public Health England and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities estimates the annual societal cost of harmful gambling at roughly £1.05–£1.77 billion and provides a range estimate for deaths by suicide associated with problem gambling. The review highlights that harms are concentrated among more deprived groups and recommends stronger prevention, treatment and data collection to meet the scale of the problem.

– Paragraph 6 – [3]

There is also a fiscal argument in play. Butler and other advocates point to the taxation of the sector as an area for reform: former chancellor Gordon Brown is quoted in the public debate describing the industry as “under‑taxed”, while independent research from IPPR suggests targeted changes to gambling taxation — particularly on higher‑harm products — could raise around £2.9 billion a year and reshape incentives within the market. Advocates say modest increases would both generate revenue for public services and reduce the attractiveness of the most damaging products.

– Paragraph 7 – [5], [1]

In Parliament Butler has tabled an early day motion to raise the profile of high‑street gambling reform, applied for a back‑bench business debate and called for deletion of the “aim to permit” clause alongside enhanced taxation. Those proposals encapsulate a broader tussle between national regulation intended to set consistent standards and councils pushing for more local autonomy to protect communities from saturation and harm. Supporters insist such changes would give residents a real say about the shape of their local retail streets; opponents warn against a patchwork of regulation that could complicate a national market.

– Paragraph 8 – [1], [6]

What emerges is a policy debate at the intersection of health, planning and finance: official data show the retail estate for gambling has shrunk from its peak, yet local concentrations persist; public‑health reviews quantify significant social costs; councils urge legal change to reclaim high streets; and independent fiscal analysis points to material revenue from tax reform. The question for ministers is whether to leave regulatory design largely as it stands or to hand communities greater powers and to press for fiscal and licensing measures intended to stem the harms that residents and clinicians say are all too real. For those on the ground, the choice feels urgent: the gamble, they argue, is to stand by and do nothing.

– Paragraph 9 – [2], [3], [1], [5]

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [4]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 3 – [2]

- Paragraph 4 – [4], [6]

- Paragraph 5 – [6], [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [3]

- Paragraph 7 – [5], [1]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [6]

- Paragraph 9 – [2], [3], [1], [5]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/aug/19/high-street-gambling-poverty-addiction – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/report/annual-report-and-accounts-2023-to-2024/annual-report-23-to-24-performance-report-overview-of-the-british-gambling – This Gambling Commission performance overview summarises the structure and scale of the British gambling sector in 2023–24. It provides authoritative regulatory statistics including counts of premises and machines, noting there were 5,995 betting shops in Great Britain and detailing numbers of casinos, bingo premises and arcades. The report also gives gross gambling yield figures and underscores the Commission’s role in licensing and enforcement. It is a primary source for changes in retail premises over time and supports claims about the high‑street presence of bookmakers and adult gaming centres, and about how the profile of land‑based gambling has evolved in recent years.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review-summary–2 – This UK government evidence review, produced by Public Health England and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, synthesises research on gambling‑related harms and their societal cost. It presents quantitative analysis estimating the combined annual cost of harmful gambling to government and society at roughly £1.05–£1.77 billion, including an estimated range for deaths by suicide associated with problem gambling (117–496 per year). The review highlights that harmful gambling is concentrated in more deprived groups, describes health and social consequences, and recommends strengthened data collection, prevention and treatment measures, framing gambling harms as a public‑health issue.

- https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/guidance/guidance-to-licensing-authorities/part-1-statutory-aim-to-permit-gambling – This guidance for local licensing authorities, published by the Gambling Commission, explains the statutory duty in the Gambling Act 2005 to ‘aim to permit’ gambling where it is reasonably consistent with the licensing objectives. The page clarifies that licensing authorities and the Commission must regulate in a way that seeks to permit gambling while moderating its impact through licence conditions, rather than seeking to prohibit it outright. It therefore sets out the legal context that local councils say limits their ability to refuse premises licences and underpins arguments for reform to give communities greater control over high‑street gambling density.

- https://www.ippr.org/articles/bookkeepers-or-changemakers-understanding-the-chancellors-choices-ahead-of-the-budget – This IPPR analysis outlines potential tax measures the chancellor could consider and includes revenue estimates for a range of options. Among these, IPPR identifies a possible new levy or increased duties on gambling which it estimates could raise around £2.9 billion per year. The briefing situates gambling tax reform within a broader fiscal strategy and argues that targeted changes to taxing higher‑harm gambling products could both raise revenue and incentivise lower‑harm activity. IPPR’s work has been cited in subsequent public debate and by politicians as evidence that modest increases to gambling taxation could generate substantial public funds.

- https://www.localgovernmentlawyer.co.uk/planning/401-planning-news/60765-group-of-local-authorities-demands-greater-licensing-and-planning-powers-over-gambling-premises – Local Government Lawyer reports that almost 40 local authorities have written to government seeking stronger licensing and planning powers to tackle the spread of high‑street gambling premises. The article explains that Brent Council led a letter calling for amendments to the Gambling Act 2005 – including reform of the ‘aim to permit’ duty – because councils feel constrained when objecting to new betting shops or adult gaming centres. It outlines the six‑point plan put to ministers, describes concerns about costly legal appeals by operators, and records cross‑authority support that frames the issue as one of public safety, health and local economic wellbeing.

- https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/gambling-addicts-betting-shops-brent-council-harlesden-willesden-neasden-b1215333.html – This Evening Standard piece focuses on Brent borough’s experience of rising gambling harms and high concentrations of licensed premises. It reports that Brent has one of the highest concentrations of gambling outlets in London, citing a figure of 81 licensed venues, and references the borough’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment which estimated gambling‑related harms cost Brent approximately £14.3 million a year. The article covers local opposition to new adult gaming centres and bookmakers, includes councillor and community views, and explains why Brent leaders have petitioned government for urgent reform to give councils more control over high‑street gambling saturation.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative is fresh, published on August 19, 2025, with no evidence of prior publication or recycling. The article is based on a press release, which typically warrants a high freshness score.

Quotes check

Score:

10

Notes:

No direct quotes are present in the article, indicating original content.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from The Guardian, a reputable organisation, enhancing its credibility.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The claims about the proliferation of gambling establishments in high streets and the call for reform align with known issues in the UK. However, the article lacks specific supporting data from other reputable outlets, which would strengthen its claims.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is fresh, original, and originates from a reputable source. While the claims are plausible, the lack of supporting data from other reputable outlets slightly reduces confidence. Overall, the narrative passes the fact-check with high confidence.