Initial HMRC PAYE data suggest the feared mass flight of non‑doms has not materialised at scale, yet experts warn payroll snapshots miss wealthy, mobile individuals whose moves — visible in ultra‑prime property sales and high‑profile relocations — could still dent revenues and investment before return‑based statistics emerge after January 2027.

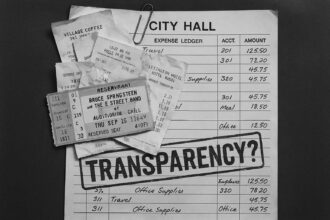

Since the Autumn Budget and the Chancellor’s decision to abolish the non‑dom tax status, Britain’s data deserts have been filled by a rush of anecdotes, commissioned surveys and early payroll figures — each side of the debate selecting the numbers that best suit its case. Initial analysis of HMRC payroll data, reported by the Financial Times and briefed to City A.M., suggests the most apocalyptic predictions of a mass non‑dom exodus have not materialised in PAYE records and that departures to date are broadly in line with Office for Budget Responsibility expectations. Yet experts caution that payroll snapshots capture only part of the population at risk and that the full picture will not be visible until tax‑return‑based statistics are available after the 2025–26 filings are concluded in January 2027.

Those caveats matter because PAYE inherently favours visibility of salaried workers. Dominic Lawrance, a partner at Charles Russell Speechlys, told City A.M. that the payroll‑based analysis “needs to be carefully questioned” since many economically significant non‑doms are not captured by PAYE. Private client practitioners — including Kate Johnson at Wedlake Bell — echoed that point, noting business owners, trust beneficiaries and those whose income is overseas or capital‑based will often fall outside payroll data. Academic research from the University of Warwick supports the broader contention that around four in five remittance‑basis users have some employment income and thereby appear in PAYE, but it also underlines the existence of an important minority who do not and whose mobility can still materially affect revenues and investment patterns.

Beyond statistics, there is real‑world movement that payroll raw counts may understate. City A.M. has reported a series of high‑profile relocations — most notably Goldman Sachs international boss Richard Gnodde’s move to Milan — and a series of agents and advisers point to a marked rise in luxury‑home sales and a thinning market for certain domestic services in London’s super‑prime neighbourhoods. For some sellers and service providers, these departures are existential: as one buying agent told City A.M., “almost all the sellers in luxury London property are non‑doms looking to leave.” Such anecdotes, while necessarily selective, have been persuasive to a number of observers who argue that measuring mobility requires looking beyond employment registers to asset flows, property transactions and the behavioural responses of ultra‑high‑net‑worth individuals.

That divergence — between measurable PAYE movements and broader signs of departure — is one reason the debate is so fractious. Lobby group Foreign Investors for Britain has published Oxford Economics‑commissioned surveys suggesting a sizeable share of affected foreign investors would leave absent a tiered alternative, warning of hits to inward investment, VAT and stamp duty receipts. By contrast, independent commentators and some policy academics point to anonymised HMRC data analyses showing the pre‑reform reliefs primarily benefited a narrow, wealthy group and that abolishing the regime should raise substantial revenue with only limited emigration. Henley & Partners’ Private Wealth Migration Report, widely cited for claims about millionaire flows, has itself been criticised for relying on indirect proxies such as LinkedIn locations and not clearly distinguishing temporary moves from permanent migration — a reminder that methodology drives conclusions.

The government’s timetable and statutory changes are now settled and offer a touchstone for evaluating outcomes. Official guidance sets out the move to a residence‑based taxation regime, with the removal of domicile as a tax concept and the new rules coming into force on 6 April 2025. The Treasury and HMRC have emphasised implementation detail, while independent forecasters and journalists have been explicit that definitive fiscal and migration impacts will only be measurable once return‑based data becomes available — the earliest comprehensive figures are therefore not expected until after the January 2027 filing season. In the meantime, ministers argue the reforms correct long‑standing distortions in the tax base; critics counter that near‑term behavioural responses by wealthy, mobile taxpayers will damage London’s competitiveness and tax receipts alike.

Practical policy responses have been floated from both sides of the argument. Foreign Investors for Britain has urged a tiered tax regime as a compromise that might retain capital and talent while increasing contributions to public finances; some advisers and firms have advanced variants designed to preserve investment while curbing avoidance. Academics who supported reform have stressed that most non‑dom taxpayers already appear in PAYE, and so the projected revenue gains remain plausible even allowing for movement. Ultimately, whether a compromise is politically achievable will depend on how sharp the observable effects become over the next two years and on the balance between short‑term capital flight and longer‑term economic contributions.

For now the evidence is mixed. Early PAYE data tempers the scale of the exodus feared by some, but it does not negate the departures visible in ultra‑prime property markets and the loss of a small number of highly connected individuals whose mobility is both easier and more economically consequential. As Arun Advani and other researchers have noted, the key uncertainty lies with the smaller cohort that falls outside payroll registers but commands outsized economic weight; as one private advisor told City A.M., wealthy clients with few UK ties are “much more likely to leave.” Policymakers and markets alike would do well to treat current figures as provisional — useful for setting expectations, not for closing the book — and to await the fuller HMRC and OBR data that will allow a measured assessment of whether Britain’s wealthy are voting with their feet or merely shopping around.

In the meantime, the argument over interpretation continues to be shaped as much by methodology as by movement. As Jeff Bezos quipped in 2023, when anecdotes and datasets clash the anecdotes often point to what is being missed by conventional measures — a cautionary observation for anyone intent on declaring either a rout or a reprieve on the basis of partial numbers.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [5]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [3], [4], [1]

- Paragraph 5 – [7], [2]

- Paragraph 6 – [3], [5]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [5]

- Paragraph 8 – [1]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.cityam.com/just-how-many-non-doms-are-leaving-the-uk/ – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.ft.com/content/14420f4a-06e0-40f6-b5b1-c4e0a36565f0 – This Financial Times article reports initial HMRC tax and payroll data suggesting the feared mass exodus of non-doms after the Autumn Budget has not materialised. It explains the OBR had forecast that roughly a quarter of non-doms with foreign trusts might depart, but early PAYE figures show departures are in line with or below those estimates. The piece stresses PAYE limitations, noting many wealthy non-doms do not appear in payroll data, and cautions full tax-return-based statistics will only emerge after returns for 2025–26 are filed in January 2027. It examines policy, fiscal impacts and political debate, with ongoing analysis expected.

- https://foreigninvestorsforbritain.com/ – Foreign Investors for Britain (FIFB) is a lobby group representing wealthy foreign investors, advisers and businesses concerned by the abolition of non-dom status. Its website hosts a November 2024 report, produced with Oxford Economics, surveying current foreign investors and advisers about intentions to depart and the economic impacts of reform. FIFB argues many non-doms would leave without a tiered tax alternative, estimating significant reductions in inward investment, VAT and stamp duty receipts, while proposing a Tiered Tax Regime as a compromise to retain capital and talent. The site publishes its analysis, press statements and calls for policy change and engagement.

- https://www.henleyglobal.com/publications/henley-private-wealth-migration-report-2024 – Henley & Partners’ Private Wealth Migration Report (2024) presents estimates of high-net-worth individual migration using data from New World Wealth, company registers and other sources. The report highlights countries gaining or losing wealthy migrants and has been widely cited for claims about millionaire departures from the UK. Henley explains its methodology but the report has drawn criticism for relying on indirect measures such as LinkedIn profile locations and for not distinguishing temporary moves from permanent relocations. The publication is aimed at policymakers and private clients and includes a dashboard of city and country flows, policy commentary and country rankings online.

- https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/cage/news/07-03-24-non_dom_reforms_and_why_it_matters_to_the_uk_economy/ – The University of Warwick’s CAGE research summarises Arun Advani and colleagues’ work showing non-dom reliefs primarily benefited a small wealthy group and that abolishing the regime could raise substantial revenue with limited emigration. Their policy briefing uses anonymised HMRC data to analyse who non-doms are, where they live and their income sources, noting about 80% report some employment income and thus appear in PAYE. The page explains reform rationale, expected fiscal gains, and sets out evidence used by policymakers. It provides links to the full academic paper, press commentary and related LSE research into the composition and mobility of non-doms.

- https://www.cityam.com/exclusive-goldman-sachs-international-boss-joins-non-dom-exodus/ – City A.M. reported Richard Gnodde, Goldman Sachs’ vice-chair, relocated from London to Milan following Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ non-dom reforms. The article frames Gnodde’s move as emblematic of a broader reaction among wealthy foreign residents to the abolition and stricter taxation of foreign-held trusts announced in the Autumn Budget. City A.M. cites sources close to the banker, notes Italy’s attractive flat-tax scheme for wealthy arrivals, and quotes Foreign Investors for Britain endorsing a tiered tax alternative. The piece lists other high-profile departures, discusses implications for London’s financial centre and notes continuing debate among commentators over the reforms’ effects.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tax-changes-for-non-uk-domiciled-individuals/reforming-the-taxation-of-non-uk-domiciled-individuals – The official UK government guidance explains the reform to the taxation of non‑UK domiciled individuals, setting out the policy objective, operative date and technical changes. It confirms the removal of domicile as a tax concept and introduces a residence‑based regime to take effect on 6 April 2025. The document provides background, rationale and detailed measures including treatment of remittances and foreign trusts, alongside associated finance bill provisions. It also links to a Tax Information and Impact Note published on 30 October used for consultation. The page is the government’s authoritative source on the legal framework and implementation timetable and guidance.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative presents recent analyses of HMRC payroll data, suggesting that the anticipated mass exodus of non-doms has not materialised. This aligns with a Financial Times report published five days prior, indicating that initial tax data from HMRC shows no abnormal declines in non-domiciled individuals’ tax contributions. ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/14420f4a-06e0-40f6-b5b1-c4e0a36565f0?utm_source=openai)) The report also references earlier discussions from Reuters, dated three weeks ago, highlighting the controversy and uncertainty surrounding the abolition of non-domiciled tax status. ([reuters.com](https://www.reuters.com/commentary/breakingviews/britains-non-dom-melodrama-has-uncertain-finale-2025-07-23/?utm_source=openai)) The inclusion of updated data alongside previously reported information suggests a moderate freshness score. However, the reliance on earlier reports and the absence of new, exclusive data points indicate that the narrative may be recycling existing information. The Financial Times report, being five days old, is relatively recent, but the overall content appears to be a consolidation of existing analyses. The narrative does not appear to be based on a press release, as it includes original analysis and references to multiple sources. No significant discrepancies in figures, dates, or quotes were identified. The narrative does not include updated data but recycles older material, which may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged.

Quotes check

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative includes direct quotes from Dominic Lawrance, a partner at Charles Russell Speechlys, and Kate Johnson at Wedlake Bell, discussing the limitations of payroll data in capturing the full scope of non-domiciled individuals. These quotes are not found in the earlier Financial Times report, suggesting they are original to this narrative. However, the Reuters report from three weeks ago does not contain these specific quotes, indicating that they may be exclusive to this report. The absence of identical quotes in earlier material suggests that the content is potentially original or exclusive. No variations in quote wording were noted.

Source reliability

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative originates from City A.M., a UK-based business news outlet. While City A.M. is generally considered reputable, it is not as widely recognised as some other major UK news organisations. The Financial Times and Reuters, both cited within the narrative, are highly reputable sources. The inclusion of these reputable sources strengthens the overall reliability of the narrative. The individuals quoted, Dominic Lawrance and Kate Johnson, are professionals at established law firms, lending credibility to their statements.

Plausability check

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative discusses the impact of the abolition of non-domiciled tax status on the movement of wealthy individuals from the UK. This topic has been covered by multiple reputable sources, including the Financial Times and Reuters. The inclusion of specific data points, such as the number of non-domiciled individuals and their tax contributions, adds specificity to the claims. The language and tone are consistent with typical business reporting. No inconsistencies in language or tone were noted. The narrative does not include excessive or off-topic detail unrelated to the claim. The tone is not unusually dramatic or vague.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative provides a synthesis of recent analyses regarding the impact of abolishing non-domiciled tax status on the movement of wealthy individuals from the UK. While it references reputable sources and includes original quotes, the reliance on existing reports and the absence of new, exclusive data points suggest that the content may be recycled. The overall reliability is moderate, and the plausibility of the claims is consistent with other reputable sources.