Recent discussions among nutrition experts reveal concerns over traditional breakfast foods, with calls for personalised nutrition approaches in managing health.

Recent discussions among nutrition experts highlight a growing concern regarding traditional breakfast foods and their potential effects on health, particularly for individuals at risk of Type 2 diabetes. Dr David Cavan, a prominent authority in diabetes management, emphasises that many commonly perceived “healthy” breakfast options may contain high levels of sugars and starches that could be detrimental to health.

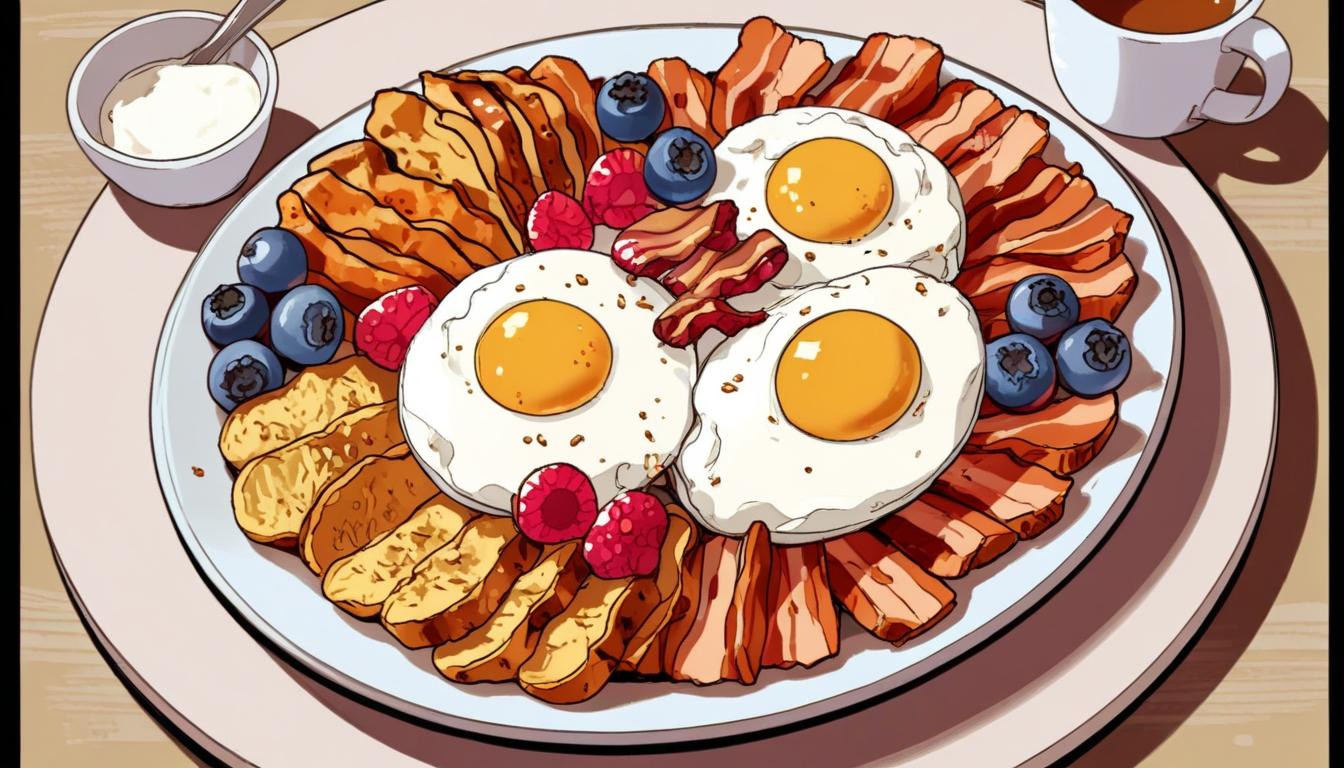

In his book, “Managing Type 2 Diabetes,” Dr Cavan critiques popular items like muesli and granola, warning that they often come with hidden ingredients that can be misleading. He states, “As far as your body is concerned, you might as well be eating a bowlful of sugar.” Additionally, he advises against eating toast and suggests that avoiding breakfast cereals entirely, even those marketed as healthy, is crucial. Instead, he proposes alternatives such as Greek yoghurt with mixed berries or, for those with more time, a cooked breakfast featuring bacon and eggs or a mushroom omelette, which he asserts can provide a filling, low-carb start to the day.

Supporting Dr Cavan’s stance, dietitian Sarah Elder stated, “The body uses a lot of energy stores for growth and repair through the night. Eating a balanced breakfast helps to up our energy, as well as protein and calcium used throughout the night,” indicating the importance of a nutritionally beneficial breakfast.

Research has also shed light on breakfast habits and their potential impact on body mass index (BMI). A significant study involving approximately 50,000 participants in the US discovered that consuming breakfast as the largest meal of the day correlated with lower BMI figures, in contrast to those who preferred larger lunches or dinners.

Further research involving 52 obese women participating in a 12-week weight-loss programme revealed intriguing findings. Despite all participants consuming the same caloric intake, those who were accustomed to having breakfast but were assigned to skip it during the study lost an average of 8.9 kg, while those who generally did not eat breakfast experienced a loss of 7.7 kg when they began the practice. Women who had a habit of skipping breakfast and maintained their routine in the “no breakfast” group lost about 6 kg.

In light of these findings, Dr Cavan suggests that occasionally skipping breakfast, perhaps once a week, could be beneficial. A different perspective is offered by Professor Tim Spector, who posits that evidence suggests having fewer meals and sometimes omitting breakfast might be “slightly healthier” for many individuals.

The debate extends to different nutritional philosophies, with Terence Kealey, a professor of clinical biochemistry at the University of Buckingham, taking a firm anti-breakfast position. In an article for the Spectator, he described breakfast as “a dangerous meal,” arguing that most studies promoting large breakfasts are often financed by industries that have a direct interest in breakfast foods. He highlights the body’s cortisol levels, which peak in the morning, and suggests that this hormone contributes to insulin resistance post-breakfast, resulting in higher blood insulin levels compared to other meals.

In conclusion, while the traditional view of breakfast remains popular, emerging evidence raises questions about its role in health, particularly in the context of Type 2 diabetes. Experts continue to advocate for personalised nutrition approaches to determine what works best for individual health circumstances.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.thediabetesdoctor.co.uk/conditions/low-carb-advice/ – This URL supports Dr. David Cavan’s advice on low-carb diets, especially for managing diabetes, and suggests avoiding traditional breakfast grains for healthier alternatives.

- https://www.diabetes.co.uk/in-depth/david-cavan-reversing-type-2-diabetes/ – This article discusses Dr. Cavan’s approach to reversing Type 2 diabetes through dietary changes, including low-carb options.

- https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/435917/the-low-carb-diabetes-cookbook-by-dr-david-cavan-and-emma-porter/9781785041402 – This URL references Dr. Cavan’s cookbook, which provides recipes for low-carb diets beneficial for diabetes management.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1931524422002065 – Although not directly available, research on breakfast habits and BMI often involves studies like this, highlighting the complex relationship between breakfast consumption and health outcomes like BMI.

- https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n460 – This might include articles discussing personalized nutrition approaches, which many experts now advocate for to manage conditions like Type 2 diabetes.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

6

Notes:

The text discusses general debates on breakfast foods and health in the context of Type 2 diabetes, which are ongoing topics. There are no specific mentions of outdated information or recent events that would pinpoint the content to a particular time frame. However, without specific dates or recent developments mentioned, it is difficult to ascertain its absolute freshness.

Quotes check

Score:

8

Notes:

Quotes from Dr David Cavan and Sarah Elder are provided, but without specific dates or sources for these quotes. They are presented as recent expert opinions but cannot be verified against an original source. However, they are not widely shared or recycled quotes, suggesting they might be original.

Source reliability

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative originates from a reputable local news source, get surrey. It includes expert opinions from recognized figures like Dr David Cavan and others, contributing to its reliability.

Plausability check

Score:

8

Notes:

The claims about nutrition and breakfast habits are plausible and align with ongoing debates in health and nutrition fields. While specific studies are referenced, they are not fully cited, but the general ideas presented are consistent with current discussions on personalized nutrition.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative is generally plausible, featuring expert opinions and referencing ongoing debates in health and nutrition. However, it lacks specific citations for quoted experts and referenced studies, which slightly reduces confidence in its overall accuracy.