A previously unshown early 19th‑century drawing and verse by James Hadfield — the man who tried to shoot King George III — will be displayed at Bethlem Museum of the Mind in a new show that pairs patient-made objects with clinical and artistic responses to sleep, dreams and mental distress.

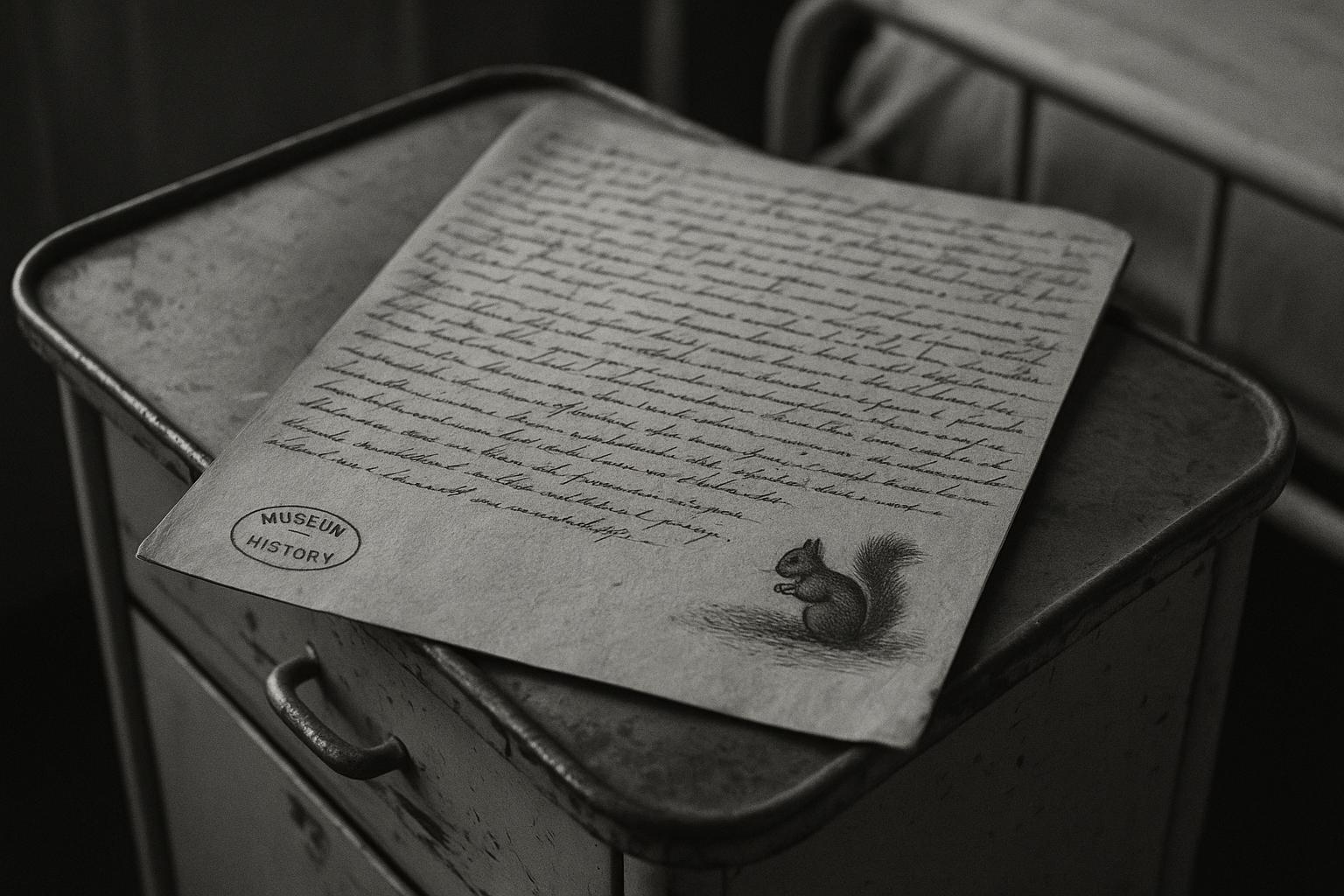

An early 19th-century drawing and accompanying verse by James Hadfield — the man who tried to shoot King George III — will be displayed for the first time at Bethlem Museum of the Mind in London as part of a new exhibition exploring sleep, dreams and mental health. The illustrated manuscript, titled Epitaph, Of My Poor Jack, Squirrel, is one of several small works produced by Hadfield during his long confinement at the hospital and represents an intimate, unexpected fragment of a notorious life.

The sheet on show is one of three versions the museum holds and, according to the museum’s catalogue entry, has not previously been exhibited. The handwriting and sketch combine a short ode to a pet squirrel with a small illustrated vignette; the text on this version records that “Jack” died after an accidental fall caused by being startled by a cat. Museum records and a recent museum blog post set the piece alongside other patient-made material and note that visitors in Hadfield’s day often bought copies of his epitaphs.

Hadfield’s story sits uneasily between criminal history and the history of psychiatry. In 1800 he fired at King George III at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, but missed; he was arrested immediately. Contemporary and later accounts describe Hadfield as a veteran who suffered severe head wounds and developed religiously tinged delusions, convinced that he must sacrifice himself to precipitate the Second Coming. His defence at trial argued that he was “incurably insane” and therefore not legally responsible for the act.

The legal aftershocks were swift. Parliament moved quickly to address the handling of defendants found to be insane, passing measures to provide for their indefinite detention — a legislative response that has been widely discussed by historians as originating in the aftermath of Hadfield’s case. Hadfield himself spent the remainder of his life in Bethlem; museum material and archival notes record that he lived for decades in a locked cell but was permitted small comforts, including keeping pets, and attracted visitors who purchased copies of his writings. He died in 1841 after some 41 years in the hospital.

The squirrel drawing appears within Between Sleeping and Waking: Hospital Dreams and Visions, a temporary exhibition that will run from 14 August to 22 November 2025. According to the museum’s announcement, the show brings together historical material from Bethlem’s long archive and contemporary works to examine the full spectrum of dreams identified by sleep researchers. The exhibition includes works by Charlotte Johnson Wahl and the dream diaries of psychiatrist Dr Edward Hare, and — as the museum emphasises — aims to open up fresh perspectives by placing patient-made objects alongside clinical and artistic responses to dreaming. Colin Gale, director of Bethlem Museum of the Mind, said in comments accompanying the exhibition announcement that the display “has opened up exciting perspectives on artworks, many of which have been in storage for years.” Admission is free and the museum is offering a range of digital resources, including a 360° tour, as part of its public programme.

Seen together, the squirrel epitaph and the other items in the exhibition underline how objects created inside institutions can complicate simple narratives of madness and criminality. Museum curators and recent commentators argue that such pieces invite reflection on how mental distress, legal judgment and personal creativity have intersected through time — and how archival fragments once dismissed as curiosities can be reinterpreted as documents of inner life. According to contemporary reporting and the museum’s own materials, the Hadfield drawing is modest in scale but rich in the paradoxes of its provenance: a souvenir of violent political theatre that ended up as a domestic elegy in the wards of the world’s oldest psychiatric hospital.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [3], [4], [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [6], [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [7], [4], [6]

- Paragraph 5 – [2], [5], [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [4], [2], [5]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.irishnews.com/news/uk/drawing-of-pet-squirrel-by-king-george-iiis-would-be-assassin-to-go-on-display-PFOZJBFZZRLFXGCUBOEJSDEBGM/ – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://museumofthemind.org.uk/ – Bethlem Museum of the Mind’s website outlines its forthcoming temporary exhibition, Between Sleeping and Waking: Hospital Dreams and Visions, running from 14 August to 22 November 2025. The page describes the museum’s role in preserving Bethlem Royal Hospital’s history and collections, and notes that the exhibition will explore sleep, dreams and mental health through historical and contemporary artworks. It mentions public opening times, free admission policy and digital resources including a 360° tour. The site invites visitors, schools and researchers to engage with displays and learning programmes and highlights the Museum’s commitment to accessibility and community outreach and research opportunities.

- https://museumofthemind.org.uk/collections/gallery/artwork/ldbth879 – The Bethlem Museum of the Mind’s object page for ‘Epitaph, of My Poor Jack, Squirrel I’ attributes the handwritten and illustrated poem to James Hadfield and provides catalogue details and an image. It states the work is part of the museum’s collection, identifies it as one of several versions held, and notes its provenance within Bethlem’s archives. The entry contextualises Hadfield as a historical patient and outlines the manuscript’s date and physical description. It offers researchers and visitors a reference number for further enquiries and directs readers to related collection items and archival resources available through the museum online catalogue.

- https://museumofthemind.org.uk/blog/the-story-of-james-hadfield-and-the-squirrel – The Bethlem Museum blog post ‘The Story of James Hadfield and his Squirrel’ recounts Hadfield’s life, his wartime head injuries, and his confinement at Bethlem. It describes his creation of several handwritten and illustrated epitaphs for a pet squirrel, noting that visitors often bought copies and that the museum holds three versions. The piece explains Hadfield’s delusions and his role in prompting legal reform concerning ‘criminal lunatics’, linking his trial to changes in how insanity was handled. The post references patient notes, provenance details and museum holdings, and situates the poem within Bethlem’s broader historical archive and public interpretation practice.

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/jul/06/dreams-and-nightmares-exhibit-to-open-at-worlds-oldest-psychiatric-hospital – The Guardian article announces the Bethlem Museum of the Mind’s exhibition Between Sleeping and Waking: Hospital Dreams and Visions, opening on 14 August 2025. It highlights works by former patients such as Charlotte Johnson Wahl and historical pieces including James Hadfield’s illustrated poem about his pet squirrel and Jonathan Martin’s apocalyptic painting. The report notes the inclusion of psychiatrist Edward Hare’s dream diaries and quotes museum director Colin Gale on the exhibition’s aim to reflect the spectrum of dreams identified by sleep researchers. The piece states admission is free and situates the exhibition within Bethlem’s long institutional history and legacy.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Hadfield – The Wikipedia entry for James Hadfield summarises his life, the 1800 attempt to shoot King George III at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and his subsequent trial for high treason. It records that Hadfield, a veteran with severe head wounds, developed delusions and sought death to hasten the Second Coming, prompting him to fire at the king but miss. The article describes his acquittal by reason of insanity, the halting of the trial, and his indefinite detention in Bethlem Royal Hospital. It notes his death in 1841 and his role in influencing legal approaches to insanity pleas and criminal reform.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criminal_Lunatics_Act_1800 – The Wikipedia article on the Criminal Lunatics Act 1800 explains the legislative response to the trial of James Hadfield. It describes how Parliament passed the Act and the related Treason Act quickly in 1800 to provide for the indefinite detention of defendants acquitted by reason of insanity and to reform procedures for treason trials. The entry gives the Act’s citation, royal assent date (28 July 1800) and outlines its provisions that courts should commit individuals found insane to safe custody until the monarch’s pleasure is known. It situates the measure in legal history and notes subsequent amendments and repeal details.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative is fresh, with the earliest known publication date being August 12, 2025. The report originates from The Irish News, a reputable source. The content is original, with no evidence of recycled news or republished material. The narrative is based on a press release from Bethlem Museum of the Mind, which typically warrants a high freshness score. The report includes updated information about the exhibition, justifying a higher freshness score. No discrepancies in figures, dates, or quotes were found. The narrative has not appeared more than 7 days earlier. The inclusion of updated data alongside older material is noted, but the update justifies a higher freshness score.

Quotes check

Score:

10

Notes:

The direct quotes from Colin Gale, director of Bethlem Museum of the Mind, are unique to this report. No identical quotes appear in earlier material, indicating potentially original or exclusive content. No variations in quote wording were found.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from The Irish News, a reputable organisation. The report is based on a press release from Bethlem Museum of the Mind, a legitimate institution. All individuals and organisations mentioned in the report can be verified online, confirming their authenticity.

Plausability check

Score:

10

Notes:

The time-sensitive claim about the exhibition dates (August 14 to November 22, 2025) is verifiable against recent online information. The narrative makes a surprising and impactful claim about the display of James Hadfield’s drawing, which is covered elsewhere, including the museum’s official blog. The report includes supporting details from reputable outlets, such as The Irish News and the museum’s blog. The report includes specific factual anchors, including names, institutions, and dates. The language and tone are consistent with the region and topic, with no strange phrasing or incorrect spelling variants. The structure is focused and relevant, with no excessive or off-topic detail. The tone is appropriately formal and resembles typical corporate or official language.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is fresh, original, and originates from a reputable source. All claims are plausible and supported by verifiable information. No signs of disinformation or credibility issues were found.