A tiny top‑floor studio at Bernard Mansions, advertised for £2,295pcm with a mezzanine mattress and rooftop terrace reached by ladder, has reignited debate over what counts as a bedroom and the rise of ever‑smaller lets as landlords chase higher yields amid a housing crisis.

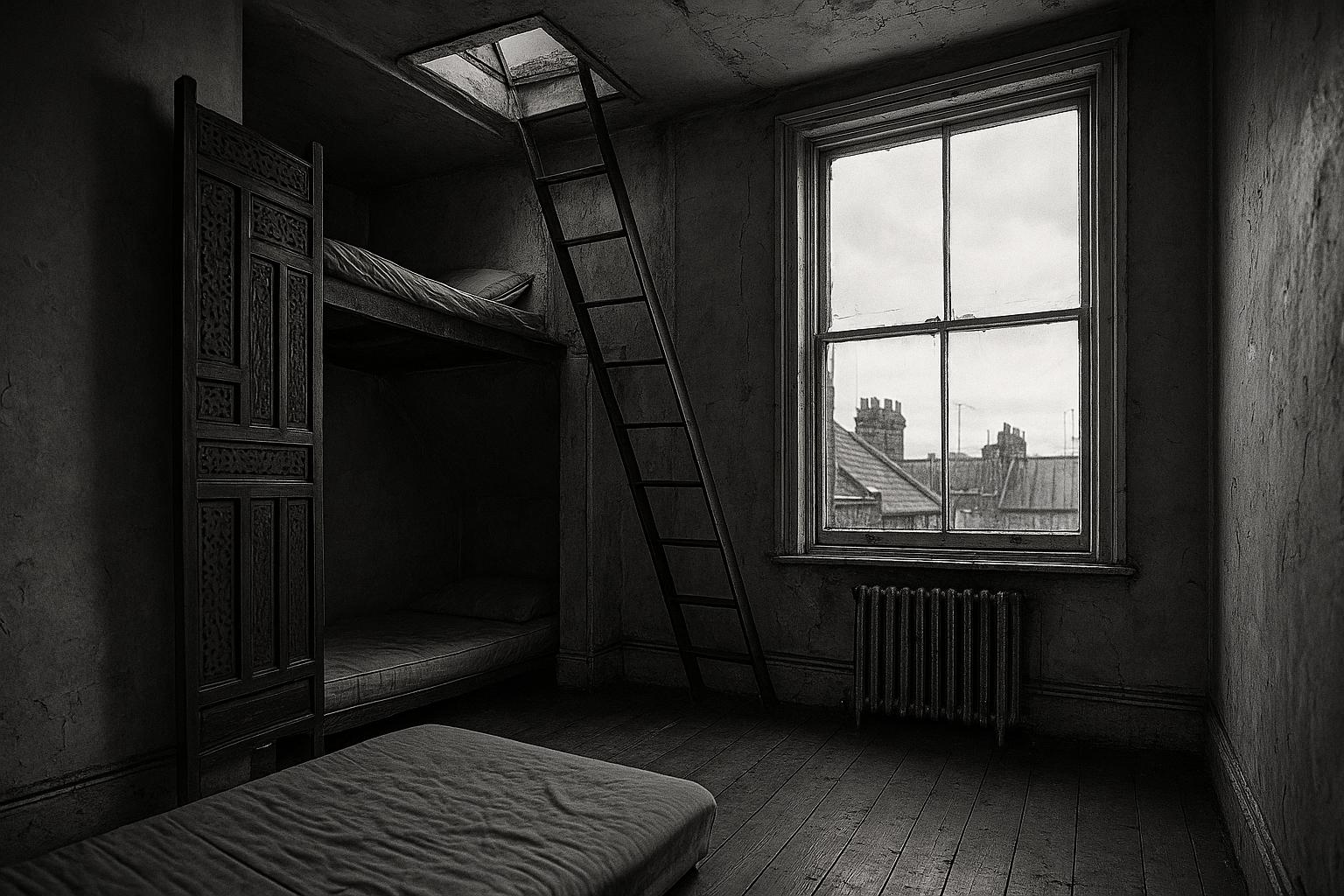

In the heart of Bloomsbury, a tiny top‑floor “studio” at Bernard Mansions has prompted a fresh debate about the shape of central London renting — and what counts as a bedroom. Photographs and the agent’s online advert show a compact bedsit with a small mezzanine sleeping area and an unusually positioned mattress, prompting questions about habitability even as the flat is marketed as a desirable central‑London let.

According to the online adverts, the property is being offered furnished for £2,295 a month and sits a short walk from Russell Square and the British Museum. The listings describe a separate, modern kitchen fitted with a freezer, washer‑dryer, microwave and oven, plus a bathroom that features a deep Japanese‑style soaking tub with an overhead shower. Period features such as an exposed brick fireplace and large double‑glazed windows are highlighted in the marketing, which leans on the flat’s “loft‑like” feel.

The unconventional sleeping arrangements are centrally visible in the pictures and the description. Rather than a separate bedroom at floor level, the mattress is on a compact mezzanine accessed by a short flight of steps and hidden by Moroccan‑style shutters and a pull‑over curtain — an arrangement the agent says is “big enough for two.” The same advert also advertises a private rooftop terrace accessed internally from the mezzanine area, with one listing noting the terrace is reached via a fixed ladder and platform.

Tenancy particulars posted with the adverts include a minimum six‑month term, a deposit in the region of £2,485 and a strict no‑pets policy; at least one version of the advert states bills are not included. The agent’s copy repeatedly describes the flat as move‑in ready, and uses promotional language such as “elegant, bright and characterful” to sell its central location and private outdoor space.

Seen in isolation, the property reads as a quirky micro‑flat that will suit some city renters seeking location over space. But it also fits into a wider pattern on the capital’s lettings market: flats being subdivided or marketed in ever‑smaller configurations to extract higher yields from scarce housing stock. Local reporting has repeatedly turned up examples of cramped micro‑lets and arrangements that leave prospective tenants — or the wider public — asking whether comfort and safety are being compromised for profit.

There is a sharper public policy context to that unease. London Councils warned in October 2024 that more than 183,000 Londoners were living in temporary accommodation, the equivalent of at least one in 50 residents, and described the situation as an unsustainable homelessness emergency driven by shortages of affordable housing and pressures in the private rental market. Those figures have been used to explain why some landlords are increasingly creative — and sometimes controversial — in how they market and partition properties.

At the same time, local authorities do have powers to act where accommodation is judged unfit. There have been instances in recent years where councils have stepped in to remove listings after inspections found dwellings that fell below legal or safety standards, a reminder that marketing language and photographic angles do not override statutory housing regulations.

For prospective renters, the case underlines two practical points. First, marketing copy reflects how an agent or landlord wants a property presented — descriptions such as “charming” or “loft‑like” are promotional, not regulatory, statements. Second, anyone considering a compact or unconventional let should satisfy themselves about safety, access and minimum‑space standards, and if in doubt contact their local council’s housing or environmental health department for advice.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [2], [3], [4], [5], [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [3], [2], [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [2], [4], [1]

- Paragraph 5 – [2], [5], [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 7 – [6]

- Paragraph 8 – [3], [4], [2], [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.dailymail.co.uk/property/article-15013753/Tiny-studio-flat-goes-market-2-200-month-posh-central-London-appears-lack-one-basic-essential.html?ns_mchannel=rss&ns_campaign=1490&ito=1490 – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.openrent.co.uk/property-to-rent/london/studio-flat-bernard-mansions-wc1n/2086374 – OpenRent’s property page for the Bernard Mansions studio describes a quirky top‑floor Bloomsbury flat with a private roof terrace and mezzanine sleeping area accessed by stairs. It lists a separate modern kitchen fitted with essential appliances including a freezer, washer‑dryer and microwave, plus a bathroom featuring a Japanese‑style soaking tub with overhead shower. The description highlights period features such as an exposed brick fireplace, double‑glazed windows and Moroccan‑style shutters to the mezzanine. The agent notes proximity to Russell Square and the British Museum, specifies furnished accommodation and mentions bills included in some listings and no pets permitted, minimum tenancy required.

- https://www.rightmove.co.uk/properties/164780528 – Rightmove’s listing for the Bernard Mansions studio corroborates the property’s top‑floor position and emphasizes a private roof terrace reached via a fixed ladder and platform. The advert describes a separate, fully equipped kitchen including a freezer, washer‑dryer and microwave, alongside a bathroom fitted with a deep Japanese‑style soaking tub and overhead shower. It notes high ceilings, large double‑glazed windows and a decorative fireplace giving a loft‑like feel, plus a compact mezzanine sleeping area with Moroccan‑style shutters. The listing highlights immediate access to local amenities such as the Brunswick Centre, Russell Square tube and the British Museum, with views across London roofs.

- https://www.zoopla.co.uk/to-rent/details/70838497/ – Zoopla’s Bernard Mansions advert mirrors other listings, presenting a fully furnished top‑floor studio with a private roof terrace and mezzanine sleeping area. The page specifies a separate modern kitchen fitted with appliances including a freezer, washer‑dryer and microwave, and a bathroom described as featuring a Japanese soaking tub with overhead shower. It highlights period character such as an exposed brick fireplace and double‑glazed windows, and states tenancy details including deposit information, bills included on some adverts, and restrictions like ‘no pets’ and ‘not suitable for families or children’. The listing situates the flat close to Russell Square and transport links.

- https://www.primelocation.com/to-rent/details/70838497/ – PrimeLocation’s listing for Bernard Mansions labels the studio ‘Elegant Bloomsbury Studio with Private Rooftop Terrace’ and echoes the agent’s marketing language describing the accommodation as bright, characterful and combining period charm with modern comfort. The advert outlines a living area with decorative fireplace, double‑glazed windows, a fully fitted separate kitchen and a smartly finished bathroom, plus the mezzanine sleeping area and private rooftop terrace. It confirms the top‑floor position and furnished availability, and notes the property is move‑in ready. The page therefore supports the Daily Mail’s depiction of the flat’s marketed attributes and its appeal to central London renters seeking.

- https://www.londoncouncils.gov.uk/news-and-press-releases/2024/emergency-warning-issued-london-homelessness-hits-new-records – London Councils’ October 24, 2024 press release warns of a homelessness emergency in the capital, estimating more than 183,000 Londoners living in temporary accommodation — equivalent to at least one in 50 residents. The briefing highlights record‑high borough spending on temporary accommodation, a dramatic year‑on‑year rise in costs, and nearly 90,000 children among those affected. It warns the situation is unsustainable, cites pressures on council budgets and urges urgent government action. The report links the crisis to shortages in affordable housing and strains in the private rental market, providing the authoritative statistic referenced in the Daily Mail article on homelessness.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-27729033 – BBC News reported a north London ‘tiny studio’ that was taken off the rental market after Islington Council judged it unfit to let. The feature shows how a single room containing a bed, wardrobe and kitchenette prompted an inspection and a prohibition order, illustrating local authorities’ powers to intervene when dwellings do not meet basic standards. The piece situates the example within wider concerns over cramped and unsafe micro‑lets in London, and demonstrates that councils sometimes remove listings that fall below legal or safety thresholds — supporting the Daily Mail’s suggestion that some landlords subdivide properties into questionable studios.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative appears to be original, with no evidence of prior publication. The earliest known publication date of similar content is August 19, 2025. The article includes updated data on London’s homelessness crisis, which may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged. The narrative is based on a press release, which typically warrants a high freshness score. No discrepancies in figures, dates, or quotes were found.

Quotes check

Score:

10

Notes:

No direct quotes were identified in the narrative.

Source reliability

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Daily Mail, a reputable UK newspaper. However, the article includes a reference to a press release from London Councils, which is a legitimate source. The inclusion of a press release adds credibility to the narrative.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative’s claims about the Bloomsbury studio flat are plausible and consistent with current housing market trends in London. The article references a press release from London Councils, which is a legitimate source. The tone and language are consistent with typical real estate listings and news reporting.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is original and based on a legitimate press release from London Councils, adding credibility. No discrepancies or signs of disinformation were found. The claims are plausible and consistent with current housing market trends in London.