A global collaboration tracking 12,000 animals across 100 species reveals critical shortfalls in protected ocean areas, highlighting the need for dynamic conservation strategies alongside human activity management.

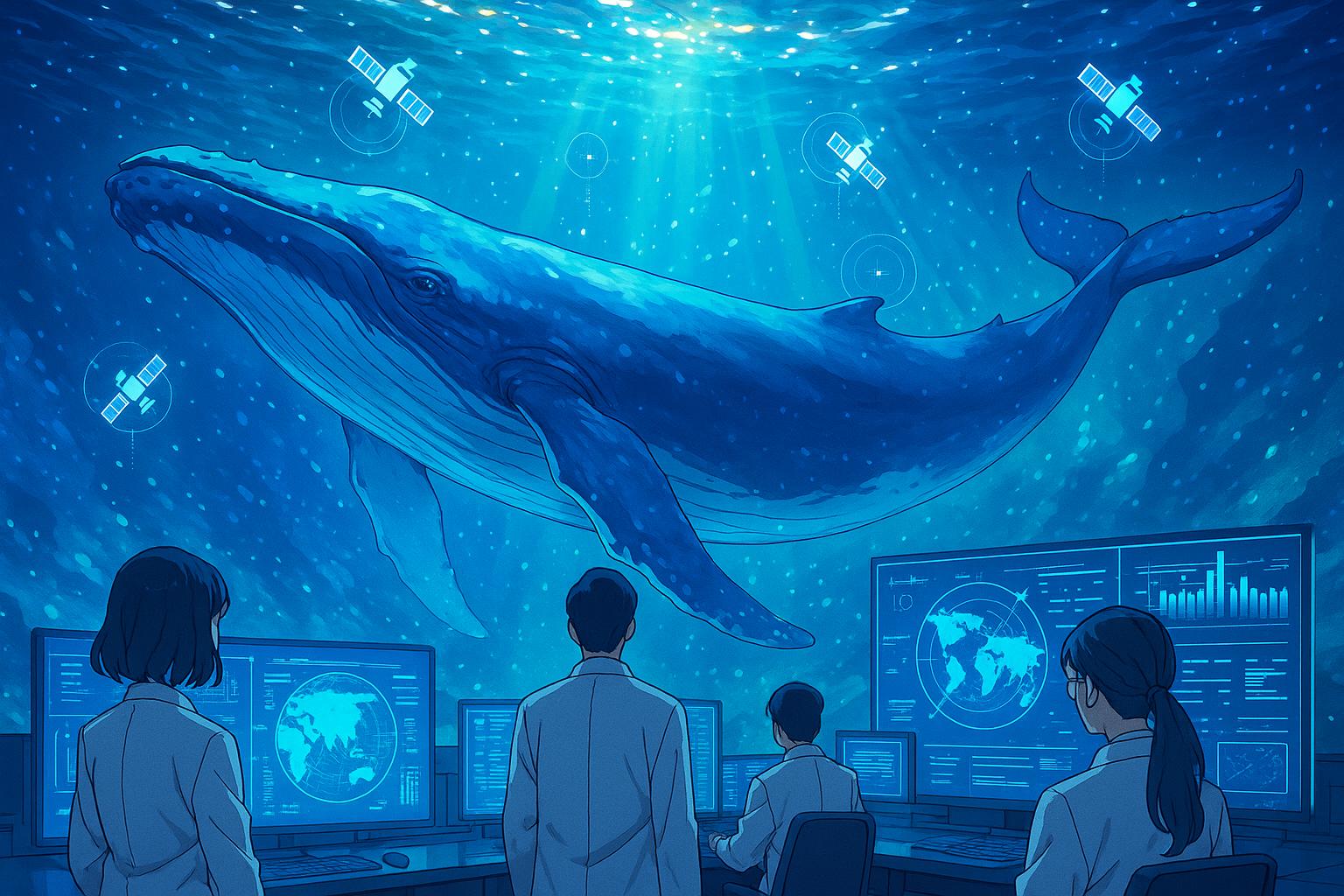

A newly published study spearheaded by Ana Sequeira at the Australian National University is shedding light on how best to protect ocean giants such as whales, sharks, and turtles. This extensive research, supported by the United Nations, synthesizes data from an impressive 12,000 satellite-tracked animals across over 100 species. The findings provide crucial insights into the migratory, feeding, and breeding behaviours of marine megafauna, as well as their interactions with human-induced threats including fishing, shipping, and pollution.

The initiative, known as MegaMove, represents a monumental collaboration involving nearly 400 scientists from more than 50 countries. Virginia Tech contributed significantly to this global effort, utilising biologging data gathered via satellite tags to formulate a comprehensive strategy for ocean conservation. Francesco Ferretti, a marine ecologist at Virginia Tech associated with the study, emphasised the necessity of understanding animal behaviour in conjunction with human activity: “It’s not just about drawing lines on a map. We need to understand animal behaviour and overlap that with human activity to find the best solutions.”

The implications of this research are particularly relevant for regions like Virginia and the wider East Coast of the United States. Ferretti pointed out that Virginia’s coastline serves as a major migratory corridor for numerous marine species. He noted the critical role of sharks in maintaining healthy marine ecosystems, which, in turn, impact local economies and fisheries. The past declines in shellfish fisheries in North Carolina serve as a stark reminder of how the loss of apex predators can destabilise entire ecosystems, affecting fisheries and, ultimately, community livelihoods.

MegaMove’s overarching goal aligns with the United Nations’ 30×30 target, which advocates for the protection of 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030. While the project proposed priority areas for protection using advanced optimization algorithms, it also highlighted a significant shortfall: “Sixty percent of the tracked animals’ critical habitats would still be outside these zones,” Ferretti stated. This underlines the necessity for additional measures beyond mere establishment of protected areas, such as amending fishing practices, adjusting shipping routes, and implementing pollution reduction strategies.

The broader relevance of Virginia Tech’s involvement in the MegaMove project reflects a growing trend to engage in international, data-driven science. Ferretti indicated that this project exemplifies a shift in marine science towards big data methodologies. As he explained, students must be equipped not only with fieldwork skills but also with expertise in data science to meet the challenges of the future. These initiatives aim to inspire the next generation of researchers while simultaneously demonstrating how local efforts can resonate on a global scale.

In addition to the technical advances in conservation strategies, the research reinforces the urgent need for dynamic marine spatial management. The MegaMove project is pivotal in enhancing understanding of how the movement of marine species fluctuates with environmental changes, thereby improving the efficacy of conservation efforts. The analysis of telemetry data from other studies further underscores the requirement for robust conservation measures adaptable to the complex behaviours of marine megafauna, reinforcing the notion that static protected areas alone may not offer adequate safeguarding against human threats.

Ultimately, the findings from the MegaMove project promise to be instrumental in reshaping our approach to marine conservation, ensuring that it is informed by rigorous scientific data and adaptable to the shifting realities of the oceans.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [3], [4]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [6], [5]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [2]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/06/250607231839.htm – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.pewtrusts.org/it/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/02/04/tracking-marine-megafauna-can-guide-more-effective-ocean-conservation – This article discusses the MegaMove project, initiated by Ana M.M. Sequeira, which brings together an international network of researchers to share data and improve understanding of marine megafauna movements, habitat use, and threats. Endorsed by the United Nations as part of the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, MegaMove aims to guide evidence-based conservation efforts for species like whales, sharks, and turtles. ([pewtrusts.org](https://www.pewtrusts.org/it/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/02/04/tracking-marine-megafauna-can-guide-more-effective-ocean-conservation?utm_source=openai))

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39116808/ – This study evaluates the effectiveness of marine protected areas (MPAs) in safeguarding important habitats for southern right whales in New Zealand. By analyzing telemetry data from 29 tagged whales, the research identifies previously unknown and currently unprotected areas used for critical behaviors such as foraging and socializing. The findings suggest that even within MPAs, whales remain vulnerable to threats like vessel traffic, highlighting the need for post-implementation assessments of MPA effectiveness. ([pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39116808/?utm_source=openai))

- https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/projects/dynamically-assess-threats-to-marine-megafauna-in-the-face-of-glo – The MegaMove project, led by Ana Sequeira, aims to develop a global approach to synthesize tracking datasets and provide near real-time diagnostics on risks for marine megafauna. By increasing understanding of how these animals’ movements vary with environmental changes, MegaMove seeks to improve conservation efforts through dynamic marine spatial management. ([researchers.mq.edu.au](https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/projects/dynamically-assess-threats-to-marine-megafauna-in-the-face-of-glo?utm_source=openai))

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/04/200417212930.htm – This article reports on research indicating that the extinction of threatened marine megafauna species could lead to significant losses in functional diversity. The study introduces the FUSE metric, identifying species like the green sea turtle and dugong as particularly important for maintaining ecological functions. The findings underscore the need for focused conservation efforts on these species to preserve marine ecosystem health. ([sciencedaily.com](https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/04/200417212930.htm?utm_source=openai))

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2019.00639/full – This article discusses the need to overhaul ocean spatial planning to improve marine megafauna conservation. It highlights the importance of integrating tracking data into conservation strategies and emphasizes the necessity of dynamic marine spatial management to address the challenges posed by the mobility of these species across multiple national jurisdictions. ([frontiersin.org](https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2019.00639/full?utm_source=openai))

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.1119428/full – This editorial highlights the role of tracking marine megafauna in conservation and marine spatial planning. It discusses the integration of animal-mounted biologging data with other technologies to improve conservation efforts, particularly for species inhabiting cryptic ecosystems. The article also mentions the MegaMove project as a global consortium focused on advancing conservation through strategic mitigation of threats guided by innovative global science efforts. ([frontiersin.org](https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.1119428/full?utm_source=openai))

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative is based on a press release from Virginia Tech dated June 7, 2025, reporting on a study published in the journal Science on June 5, 2025. This indicates high freshness, as the information is current and directly linked to recent publications.

Quotes check

Score:

10

Notes:

The direct quote from Francesco Ferretti, a marine ecologist at Virginia Tech, appears to be original, with no prior matches found online. This suggests the content is potentially exclusive.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from a reputable institution, Virginia Tech, and is supported by a peer-reviewed publication in the journal Science. This enhances the credibility of the information presented.

Plausability check

Score:

10

Notes:

The claims made in the narrative align with known scientific research on marine megafauna conservation. The involvement of nearly 400 scientists across more than 50 countries in the MegaMove project adds to the plausibility.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is based on a recent press release from Virginia Tech, reporting on a study published in the journal Science on June 5, 2025. The information is current, originates from a reputable institution, and is supported by a peer-reviewed publication, indicating high credibility and freshness.