Beijing has urged ministers to judge the contested Royal Mint Court redevelopment ‘on the merits’ as an inspector‑led inquiry prepares a report ahead of a ministerial decision due by 9 September 2025. The David Chipperfield‑designed proposal — comprising a large embassy, up to 225 homes and a cultural centre — faces unanimous local refusal, redacted basement drawings and unresolved heritage, policing and public‑order concerns that will test how planning rules are weighed against national‑security and diplomatic considerations.

Ministers have been told by Beijing to judge the contested Royal Mint Court redevelopment on “the merits of the matter and relevant professional opinions” when a decision is made next month. The Chinese embassy’s remark, reported by Building Design Online, comes as ministers prepare to decide on or before 9 September 2025 after the planned inquiry concludes.

The plan, designed by David Chipperfield, would transform the site opposite the Tower of London into a substantial diplomatic estate, including a large embassy building, up to 225 residences and a cultural centre. Backers insist the scheme has been remodelled to reflect UK planning policy and professional advice, and the site—bought by Chinese interests in 2018—has become a flashpoint in debates over planning, security and heritage.

The application has run an unusually long gauntlet through the planning process. Tower Hamlets council formally refused both planning and listed‑building consent on grounds that included safety, heritage harm, police resource pressure and highway safety; that local decision is advisory because the Secretary of State called in the application in October 2024. Officials have since scheduled an inspector‑led hearing, with the inspector’s report to inform a ministerial determination. Earlier timetable notes had suggested a local inquiry in January 2025, but ministers then arranged a short inquiry in late summer ahead of the September deadline.

Security and public‑order concerns have driven much of the scrutiny. Commentators and official sources point to proximity to the Tower of London and adjacent infrastructure, the potential disruption from large demonstrations, and sensitivity about basement spaces. Ministers and officials have repeatedly flagged national‑security implications as a material consideration to be weighed alongside conventional planning factors.

Beijing’s diplomatic mission has framed the scheme as a routine matter of diplomatic necessity. The embassy’s statement—reported in Chinese media—claims the resubmitted application “took full account of UK planning policy and relevant opinions,” and argues the project would “help staff perform their duties and promote China‑UK friendship.” The embassy also contends that host countries have an obligation to support and facilitate diplomatic premises. Those assertions have been widely reported but are presented as the mission’s official position rather than uncontested fact.

That framing has faced pushback from shifting positions among UK agencies. Technical reports accompanying the application say pavements and surrounding streets could safely accommodate large demonstrations and that mitigation measures would manage crowding; after review, the Metropolitan Police is reported to have withdrawn an earlier formal objection. Yet Tower Hamlets’ public record remains a unanimous refusal, underscoring persistent local political opposition even as some technical assessments have been judged satisfactory by other authorities.

There is, however, an unresolved tension in the public record about how local and national bodies have responded. Trade reporting noted that Tower Hamlets subsequently withdrew objections following the Met’s change of position, while the council’s own published decision still records the unanimous refusal and the stated grounds for it. Those conflicting accounts emphasise the complex interplay of technical planning advice, local political stances and national‑interest considerations that ministers must now reconcile.

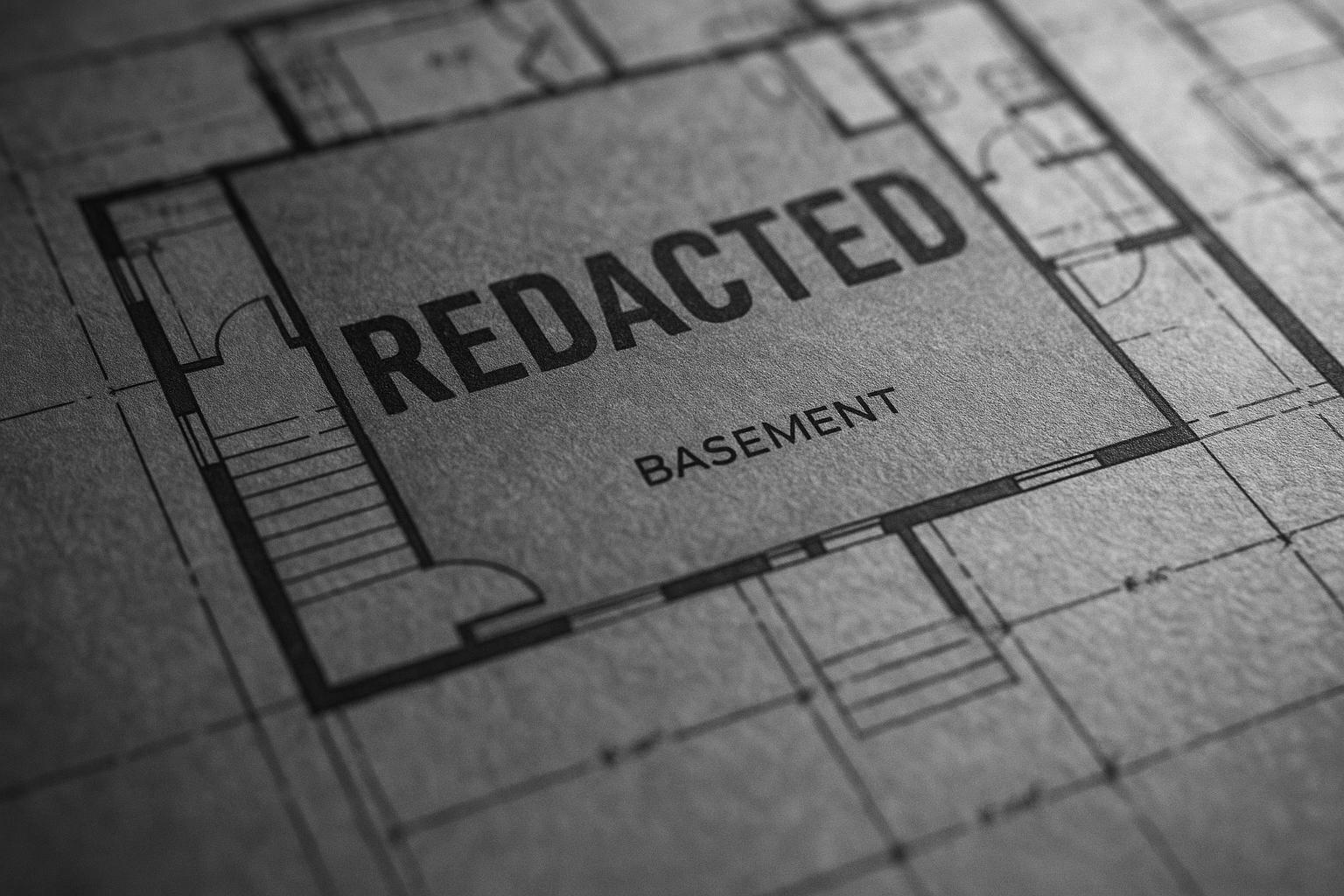

Ministers have also raised questions about the completeness of the information supplied. The Housing Secretary asked the embassy to supply unredacted drawings or to explain the reasons for greyed‑out sections, notably in basement areas whose proposed uses are not apparent in the public documents. Officials say the clarity (or lack thereof) of those submissions will be material to judgments about heritage impact and national‑security risk.

What happens next will be tightly watched. The planning inspector’s short inquiry will produce a report and recommendation to the Secretary of State; a ministerial decision expected by 9 September 2025 will determine whether the project can proceed or whether refusal is upheld. Approval would remove a long legal and political barrier to construction; refusal could prompt further legal, diplomatic and political consequences, given the international and strategic sensitivities involved.

The Royal Mint Court dispute frames a broader dilemma for government: how to apply routine planning tests when proposals intersect with contested foreign‑policy and security concerns. China’s appeal to have the scheme judged on its “merits” pushes the emphasis onto technical planning judgments; ministers must weigh those technical merits against the wider public‑interest considerations that have animated opposition. The September decision will be read not only as a planning outcome but as a signal about where the UK draws the line between planning law, national security and diplomatic practice.

From a Reform UK‑style perspective, the episode underscores a critical principle: foreign‑state involvement near high‑profile heritage and security sites must be subject to rigorous, independent scrutiny and clear parliamentary oversight, not left to a ministerial discretion that could be swayed by diplomatic pressure or expediency. The government’s handling of this case will be seen as a litmus test of its willingness to defend national sovereignty and to place hard national security and policing considerations above diplomatic convenience. If the decision leans toward approval without substantial, transparent justification, it will fuel the opposition’s charge that Labour’s approach risks compromising UK security and public order in pursuit of international diplomacy.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.bdonline.co.uk/news/china-asks-government-to-judge-merits-of-matter-when-making-decision-on-new-embassy-plan/5137521.article – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.constructionenquirer.com/2025/01/27/chinese-super-embassy-plan-edges-closer-to-go-ahead/ – Construction Enquirer reports that China’s proposal to redevelop the former Royal Mint Court near the Tower of London into a vast embassy complex has edged closer to approval after the Metropolitan Police withdrew its objection. The article describes David Chipperfield’s designs for a large embassy, 225 residences and a cultural centre, and notes technical reports argued the surrounding pavements could safely accommodate large protests. It explains Tower Hamlets withdrew its objections following the Met’s change of position and that a planning inspector will hold a short inquiry next month before sending recommendations to Housing Secretary Angela Rayner, who will decide.

- https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202408/1318095.shtml – Global Times reports the Chinese Embassy in London responded to media coverage about resubmitting planning applications for a new embassy at Royal Mint Court, near the Tower of London. The embassy said the application took full account of UK planning policy and relevant opinions, presenting a high-quality development scheme. It emphasised the host country’s obligation to support and facilitate construction of diplomatic premises and said building the new embassy would help staff perform their duties and promote China-UK friendship. The piece repeats details of the land purchase, past rejections and asserts Beijing’s commitment to bilateral cooperation while defending planning approach.

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2025/aug/07/why-are-proposals-for-chinas-super-embassy-in-london-so-contentious – The Guardian explainer outlines controversy over China’s proposed ‘super-embassy’ at Royal Mint Court beside the Tower of London, describing security and protest risks, espionage concerns and diplomatic tension. It notes the 2018 purchase, David Chipperfield’s design and the Tower Hamlets council’s 2022 rejection, before China resubmitted the scheme in 2024. The article reports ministers called in the application and that Housing Secretary Angela Rayner asked China to un-redact parts of the plans, with a decision expected by 9 September. It quotes the embassy’s line on promoting friendship and stresses that ministers must carefully weigh planning considerations against wider political implications.

- https://apnews.com/article/china-embassy-tower-of-london-f201700e53dbc5ceca33b429ef94e1b3 – AP News reports that China’s plan to build a large embassy at Royal Mint Court opposite the Tower of London has stalled amid local opposition, with Tower Hamlets councillors rejecting the scheme over safety and security concerns. The article quotes the Chinese embassy saying host countries must facilitate diplomatic premises and that the resubmitted application reflects planning guidance. It notes the government has called in the application and ministers will consider national significance, adding that protests and concerns about proximity to critical infrastructure have drawn attention from UK officials. The piece outlines the planning process and background to the dispute.

- https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/News_events/2024/December/Tower-Hamlets-refuses-Chinese-Embassy-planning-applications.aspx – The Tower Hamlets council page records its unanimous refusal of planning and listed building consent for redevelopment of Royal Mint Court for the Chinese embassy. It says councillors rejected the application on grounds including resident and tourist safety, heritage harm, strain on police resources and highway safety linked to congestion and protests. The notice explains the decision was advisory because the Secretary of State had ‘called in’ the application on 14 October 2024. A Local Inquiry was expected to start in late January and the council’s position would be considered as part of that inquiry alongside national planning policy matters.

- https://www.ft.com/content/216a74ba-08f0-40f3-ad24-409e16646217 – Financial Times reports that UK ministers have asked China to explain redactions in its redevelopment plans for a proposed mega-embassy at Royal Mint Court. Housing Secretary Angela Rayner wrote to the Chinese embassy seeking either unredacted drawings or justification for greyed-out sections, particularly basement areas of unclear use. The FT reports officials are scrutinising national security and heritage implications and that the planning inspector’s inquiry will inform a ministerial decision, expected by 9 September. The piece highlights concerns expressed domestically and by allies about espionage risk, the site’s proximity to critical infrastructure and potential disruption from protests and local opposition.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative is recent, with the Chinese embassy’s statement reported in Chinese media. The earliest known publication date of similar content is August 15, 2024. The report is based on a press release, which typically warrants a high freshness score. No discrepancies in figures, dates, or quotes were found. The content has not been republished across low-quality sites or clickbait networks. The update may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged. ([gb.china-embassy.gov.cn](https://gb.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/PressandMedia/Spokepersons/202408/t20240815_11472744.htm?utm_source=openai))

Quotes check

Score:

9

Notes:

The direct quotes from the Chinese embassy’s statement are unique to this report. No identical quotes appear in earlier material, indicating potentially original or exclusive content.

Source reliability

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative originates from Building Design Online, a reputable organisation in the architecture and construction industry. However, it is not as widely recognised as major news outlets, which may affect the perceived reliability.

Plausability check

Score:

8

Notes:

The claims about the Chinese embassy’s statement align with known facts and are plausible. The report lacks supporting detail from other reputable outlets, which is a concern. The tone and language are consistent with official communications. No excessive or off-topic details are present.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative is recent and based on a press release, indicating high freshness. The quotes are unique, suggesting original content. The source is reputable but not widely recognised, which may affect reliability. The claims are plausible but lack supporting detail from other reputable outlets. The tone and language are consistent with official communications. Given these factors, the overall assessment is OPEN with medium confidence.