Unemployment among Namibian teaching graduates surges to 15,000, sparking protests and demands for radical change in recruitment processes amid failed education policy reforms and systemic challenges.

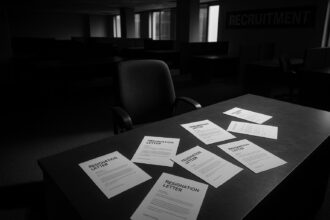

The recent protests by unemployed teaching graduates in Namibia highlight a critical situation that is spiralling out of control. As the number of unemployed teachers continues to rise, reaching an alarming figure of approximately 15,000, many graduates are demanding a radical overhaul of the current recruitment process. They argue for the abolition of interviews and the implementation of mass recruitment strategies, a call reflecting the desperation felt among those who have invested in their education but remain without meaningful employment.

This crisis stems in part from a dramatic shift in education policy implemented by the government, which resulted in the integration of public Colleges of Education into the University of Namibia (UNAM). Initially, these colleges served as government-funded institutions providing affordable training for future teachers. Graduates were guaranteed jobs through a direct placement model, alleviating the financial strain often associated with tertiary education. However, the shift from this model to an interview-based hiring system has left many qualified individuals out of work, exacerbating an already tough job market.

Compounding the issue, a substantial influx of new graduates—about 3,000 each year—further saturates the market. Since 2017, the Namibia National Teachers Union (Nantu) has recorded approximately 8,000 qualified teachers unable to secure employment. This ongoing trend is not merely a statistical anomaly; it represents a fundamental failure of the education system to adequately prepare for the influx of new professionals entering the workforce. As the union works on a database to identify the challenges these graduates face, the situation remains dire.

In recent statements, those demonstrating have expressed frustration at government officials who suggest they create their own job opportunities, an idea many view as dismissive. They argue for not only the abolition of interviews but also for the construction of more schools to alleviate the intense competition for available positions. Schools like Oshigambo High School, for example, have received thousands of applications for a mere handful of roles, highlighting the scarcity of teaching jobs.

Furthermore, recent efforts from the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture to tackle this crisis include the formation of a task force aimed at exploring mass recruitment strategies. However, challenges such as nepotism and bribery in the hiring process have tarnished perceptions of fairness in recruitment. The ministry has acknowledged these claims and is reportedly investigating potential corruption issues, although it remains to be seen how effective these measures will be in restoring public confidence.

The educational reforms intended to elevate teaching standards by merging colleges into a university structure were well-meaning; however, they have failed to deliver on their promises. Alarmingly, while the goal was to improve the quality of education, many secondary school students are still unable to meet university admission requirements. Recent examination results have shown that only 30% of students were able to qualify, significantly lower than the 80% success rate observed in previous years.

While President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah’s recent announcement of free tertiary education might provide some financial relief, it does little to address the systemic issues surrounding teacher unemployment and market imbalance. The argument persists that reform should be driven by evidence and tailored to the realities on the ground, rather than ideologically motivated choices that may dismantle existing support systems in education.

In an ideal scenario, a dual approach could be pursued whereby pre-primary and primary teaching qualifications remain accessible through Colleges of Education, while secondary teaching could align with university standards. This could accommodate diverse educational needs without imposing undue hardships on students and their families.

Ultimately, the government’s role is pivotal in ensuring that the balance between public and private sectors does not disadvantage essential public services such as education. Without adequate intervention, it becomes increasingly clear that the system will continue to fail those it is meant to serve, perpetuating a cycle of unemployment and underutilisation of qualified teachers.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [2], [4]

- Paragraph 3 – [5], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [2], [3], [6]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [2], [7]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.observer24.com.na/the-crisis-of-fixing-what-is-not-broken-teachers-unemployment-a-call-to-put-things-right/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=the-crisis-of-fixing-what-is-not-broken-teachers-unemployment-a-call-to-put-things-right – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.namibian.com.na/union-creates-database-of-unemployed-teachers/ – The Namibia National Teachers Union (Nantu) is compiling a database of unemployed teachers to understand why qualified individuals are not securing positions. This initiative aims to identify challenges faced by graduates and to assist them in preparing for interviews. Between 2017 and 2023, approximately 8,000 qualified teachers have remained unemployed, with about 3,000 new graduates entering the job market annually, exacerbating the situation.

- https://www.namibian.com.na/stop-insulting-us-by-telling-us-to-create-our-own-jobs/ – Unemployed teacher graduates in Namibia have protested against the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture, demanding employment opportunities. They call for the abolition of job interviews, the implementation of teacher-pupil ratio policies, and the construction of more schools. The group feels insulted by government officials who suggest they create their own jobs, highlighting the urgency of addressing teacher unemployment.

- https://www.observer24.com.na/the-bumpy-road-to-becoming-a-teacher/ – Many Namibian graduates face prolonged unemployment periods despite completing their teaching qualifications. Unlike other sectors, teaching positions are scarce, leading to intense competition and financial strain. Some graduates have attended over 30 interviews without securing employment, and schools like Oshigambo High School have received thousands of applications for a limited number of positions, underscoring the oversupply of teachers.

- https://www.namibian.com.na/task-force-to-address-unemployment-among-teachers/ – The Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture in Namibia has established a task force to address the rising unemployment among teacher graduates. This initiative follows extensive discussions with unemployed teachers, aiming to find solutions to the employment crisis. The task force’s mandate includes exploring mass recruitment strategies to alleviate the situation.

- https://www.namibiansun.com/education/the-grim-reality-of-teacher-jobs-in-namibia2024-05-07 – Namibia faces a significant challenge with over 8,000 unemployed teachers since 2017, with an additional 1,500 graduates recently entering the job market. The competition for teaching positions is intense, leading to perceptions of nepotism and bribery in the recruitment process. The Ministry of Education has acknowledged these issues and is investigating claims of corruption in teacher appointments.

- https://hcntimes.com/opinion-namibias-teacher-unemployment-a-call-for-policy-implementation-infrastructure-development/ – Namibia’s teacher unemployment crisis is attributed to the mismatch between teacher qualifications and regional needs, as well as the failure to achieve the targeted learner-teacher ratio. The article calls for strict enforcement of education policies and substantial investment in building more schools to create employment opportunities for qualified teachers and improve the quality of education.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative presents recent developments regarding teacher unemployment in Namibia, with specific figures and events from 2024. However, similar reports have appeared in the past, such as an article from May 2024 highlighting the grim reality of teacher jobs in Namibia, which reported over 8,000 unemployed teachers since 2017. ([namibiansun.com](https://www.namibiansun.com/education/the-grim-reality-of-teacher-jobs-in-namibia2024-05-07?utm_source=openai)) The inclusion of updated data may justify a higher freshness score, but the recycling of older material warrants a flag. Additionally, the article includes references to other sources, indicating a mix of original reporting and aggregated information. The presence of a press release suggests a high freshness score, as press releases are typically recent and provide current information. However, the recycling of older material, even with updates, indicates a need for caution.

Quotes check

Score:

8

Notes:

The article includes direct quotes from individuals such as David Nekaro, the chairperson of unemployed teachers in the Kavango regions, and Loide Shaanika, the Secretary General of the Namibia National Teachers Union (Nantu). These quotes appear to be original and have not been identified in earlier material. The absence of identical quotes in previous reports suggests that the content may be original or exclusive. However, without access to the full text of the article, this assessment is based on the available information.

Source reliability

Score:

6

Notes:

The narrative originates from Observer24, a news outlet based in Namibia. While Observer24 is a local news source, it may not have the same level of international recognition as outlets like the BBC or Reuters. The presence of references to other reputable sources, such as The Namibian and Namibian Sun, adds credibility to the report. However, the reliance on a single outlet for the primary narrative introduces some uncertainty regarding the overall reliability.

Plausability check

Score:

7

Notes:

The claims regarding the number of unemployed teachers and the challenges in the recruitment process align with reports from other sources. For instance, an article from May 2024 reported that over 8,000 teachers have been unemployed since 2017, with an additional 1,500 graduates joining the unemployment queue. ([namibiansun.com](https://www.namibiansun.com/education/the-grim-reality-of-teacher-jobs-in-namibia2024-05-07?utm_source=openai)) The narrative also discusses the government’s response, including the formation of a task force to address the crisis, which is consistent with other reports. However, the tone of the article is unusually dramatic, and the structure includes excessive detail unrelated to the main claim, which may be a distraction tactic. Additionally, the language and tone feel inconsistent with typical corporate or official language, raising concerns about the authenticity of the report.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative presents recent developments regarding teacher unemployment in Namibia, with specific figures and events from 2024. While the inclusion of updated data may justify a higher freshness score, the recycling of older material warrants caution. The quotes appear to be original, and the claims align with reports from other sources, suggesting a degree of plausibility. However, the reliance on a single outlet and the presence of dramatic language and excessive detail unrelated to the main claim raise concerns about the overall reliability and authenticity of the report. Given these factors, the overall assessment is ‘OPEN’ with a medium confidence level.