The No Mow May campaign, encouraging reduced grass mowing to support pollinators, is gaining momentum across 56 UK councils in 2024 despite financial and ecological debates. Advocates argue it fosters vital habitats in urban green spaces, while critics highlight cost overruns and uncertain long-term impacts.

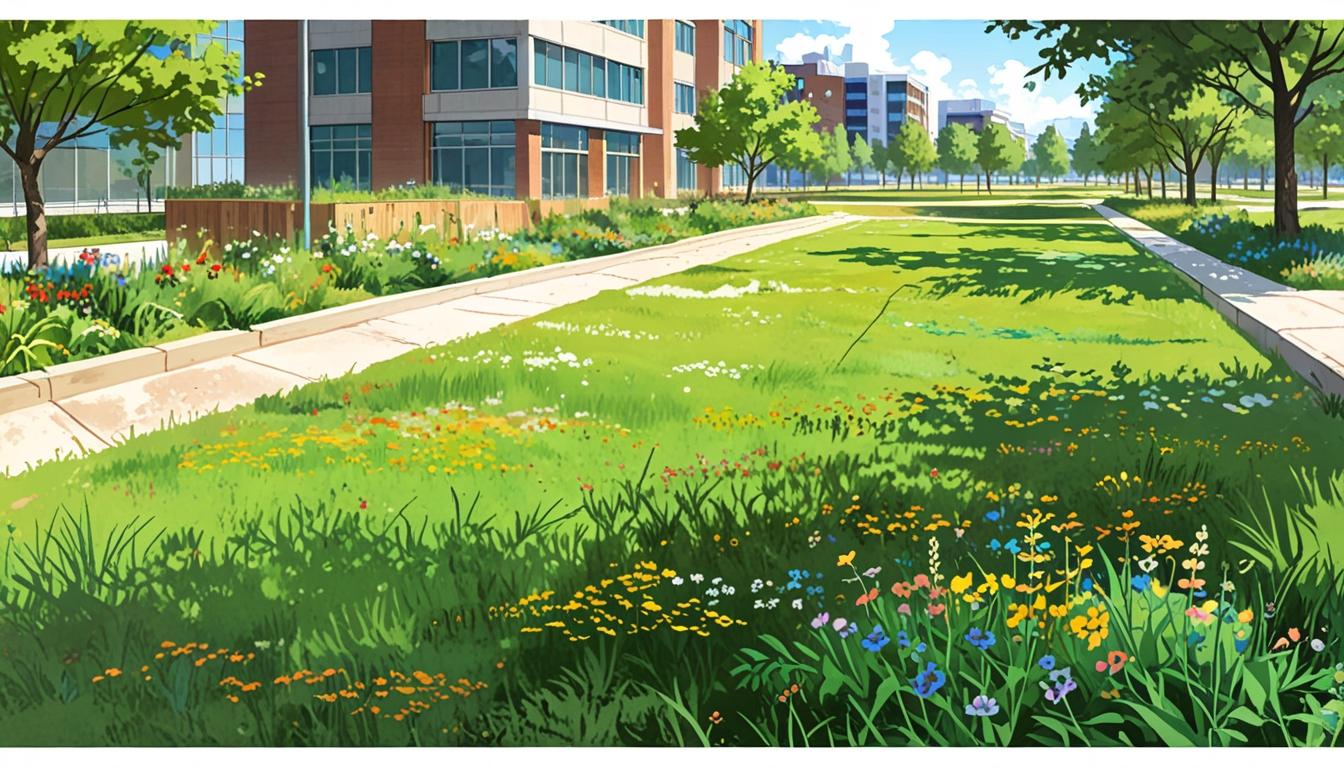

In recent years, a movement known as “No Mow May” has gained traction in parts of the UK, encouraging individuals, councils, and organisations to pause mowing during the month of May to benefit urban biodiversity. The campaign, which began in 2019 through the efforts of the conservation group Plantlife, aims to provide early spring pollinators such as bees with vital food sources found in daisy, buttercup, dandelion, and other wildflowers that flourish when grass is left uncut.

The idea has been embraced by numerous UK local authorities, including the London borough of Lambeth and 54 other councils, as well as some communities in the United States. It encourages letting council-managed green spaces grow wild during May. Local residents have observed the effects, with wildflowers like red clover carpeting green areas in some urban settings. However, once May ends, many councils resume mowing, as was the case in Lambeth, raising questions about the lasting impact of the initiative.

Critics of No Mow May point to limited evidence supporting sustained biodiversity benefits beyond the initial growth period. Some may also cite financial implications; for example, Warwick District Council reported a £29,000 budget overspend associated with the heavier grass cutting required after a month of longer growth. Additionally, a 2020 American study previously used to support No Mow May was found to contain significant errors, causing major media outlets such as the New York Times to retract related stories. Debate continues surrounding the campaign’s claims regarding carbon reduction and cost savings.

Despite these concerns, numerous reports highlight a sharp decline in the UK’s flying insect populations, with a Buglife and wildlife trust study in 2021 noting a decrease of up to 60% over two decades. Urbanisation is cited as a key factor contributing to this decline in the 2019 State of Nature Report. Groups like Nature 2030 stress the potential of the UK’s 85,000 hectares of publicly accessible green spaces to serve as interconnected wildlife corridors, aiding pollinator recovery efforts. The Wildlife Trust has noted that pollinators contribute to the productivity of UK crops valued at around £690 million annually.

Surprisingly, public grass verges cover approximately 1.2% of UK land. An ecological newsletter, Inkcap, published a 2021 report on verge cutting, revealing unintended consequences of changing mowing practices. Reduced mowing frequencies, sometimes adopted for budget reasons—as seen in Sheffield—require different grass clipping management, which can affect soil nutrient levels. Wildflowers tend to thrive in poorer soils, and road verges now host nearly half of the UK’s wildflower species, including rare varieties such as harebell, tower mustard, spiked rampion, and multiple types of orchids. These rich habitats provide abundant nectar for millions of pollinators.

Frequent mowing has been shown to negatively impact biodiversity while presenting financial challenges. Tower Hamlets, one of London’s less affluent boroughs, reportedly spends £10,000 annually on mowing just 0.12 miles of grass verge every fortnight over six months, costing around £52 per square metre.

Despite the mixed evidence, No Mow May continues to expand. According to Plantlife’s Mark Schofield, 56 UK councils have registered to participate in 2024. Some councils claim longer-term cost savings and ecological benefits; Dorset council reports a reduction in mowing expenses by nearly half after seven years of involvement. Schofield explained that the primary goal of the initiative is to “depart from tradition and manage areas so they flower and provide shelter for wildlife throughout the summer.” He also emphasised the potential of utilising margins of publicly owned football pitches, which currently are typically fully mown, saying that creating 10-metre unmown margins around pitches could create significant wildlife habitats equivalent in size to 100 football pitches per county.

Visitors to these spaces, such as families in London, have been prompted to reconsider aesthetic expectations of urban greenery. Rather than viewing uncut lawns as neglected or untidy, advocates encourage seeing them as vibrant habitats supporting an array of wildlife. This shift in perspective aligns with the thoughts of American writer Michael Pollan, who described conventional mowing as “nature purged of sex and death.”

Some areas are further extending the duration of growth pauses beyond May. For instance, Ealing Council has initiated a “Let It Bloom June” campaign, signalling a continuing evolution of urban ecological management strategies.

The Financial Times is reporting these developments as part of the broader emerging conversation around urban biodiversity and green space management.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.ft.com/content/83299d51-e17a-478f-b917-0f6d6c36b1c3 – This article discusses the origins of ‘No Mow May’ in 2019 by Plantlife, its adoption by UK councils, and the observed effects on urban biodiversity, including the growth of wildflowers like red clover in urban areas.

- https://www.plantlife.org.uk/campaigns/nomowmay/ – Plantlife’s official page on ‘No Mow May’ provides details on how individuals and councils can participate, emphasizing the initiative’s goal to support pollinators by allowing wildflowers to flourish.

- https://www.plantlife.org.uk/our-work/local-councils-and-no-mow-may/ – This page highlights the involvement of various UK councils in ‘No Mow May’, including Lincolnshire County Council’s partnership with the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust to protect road verges as Roadside Nature Reserves.

- https://www.plantlife.org.uk/this-is-what-a-no-mow-may-lawn-looks-like-your-results/ – Plantlife showcases participant-submitted photos of ‘No Mow May’ lawns, illustrating the transformation of urban green spaces into vibrant habitats supporting a variety of wildflowers and pollinators.

- https://www.plantlife.org.uk/campaigns/your-no-mow-may-lawn-guide/ – Plantlife offers guidance on preparing and maintaining a ‘No Mow May’ lawn, including tips on mowing practices and selecting suitable wildflowers to enhance biodiversity.

- https://www.ft.com/content/10b2fef4-49ab-48db-9c32-a30a44b686cf – An article reflecting on the author’s experience participating in ‘No Mow May’ in Ann Arbor, Michigan, discussing the initiative’s impact on pollinator habitats and the author’s personal observations.

- https://www.ft.com/content/83299d51-e17a-478f-b917-0f6d6c36b1c3 – Please view link – unable to able to access data

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative references current events like the participation of UK councils in 2024 and a 2021 report, suggesting it is relatively fresh. However, some details and studies mentioned date back a few years.

Quotes check

Score:

9

Notes:

A quote from Mark Schofield highlights specific details about the campaign, but no direct evidence of earlier references to this quote could be found. The non-specific nature of Michael Pollan’s referenced statement, ‘nature purged of sex and death,’ makes it difficult to verify its first appearance.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Financial Times, a well-known reputable publication.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

Claims about biodiversity benefits and specific council actions are plausible, though both critics’ concerns and limited lasting impacts are noted. The involvement of multiple councils and the expansion of the initiative support its plausibility.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative is deemed reliable due to its origins from the Financial Times, while the recent participation figures and expansion of the ‘No Mow May’ initiative support its freshness and plausibility.