Freedom-of-information returns compiled by the Royal College of Nursing show 4,054 recorded incidents of physical violence against A&E staff in 2024, broadly double the figures reported in 2019. Unions and clinicians link the surge to overcrowding, long waits, understaffing and rising mental‑health presentations, and say immediate protection measures must be paired with investment to end corridor care.

Nurses working in hospital accident and emergency departments are facing what their union describes as an “abhorrent” and rapidly rising level of physical violence, with freedom-of-information returns collected by the Royal College of Nursing showing thousands of recorded assaults in recent years. According to the RCN’s survey of trusts, 4,054 incidents of physical violence against A&E staff were recorded in 2024 – broadly double figures reported in 2019 – a trend the union and health commentators warn is being driven by overcrowding, long waits and chronic staffing shortfalls. (According to the original reporting, the RCN compiled its figures from FOI responses across trusts.)

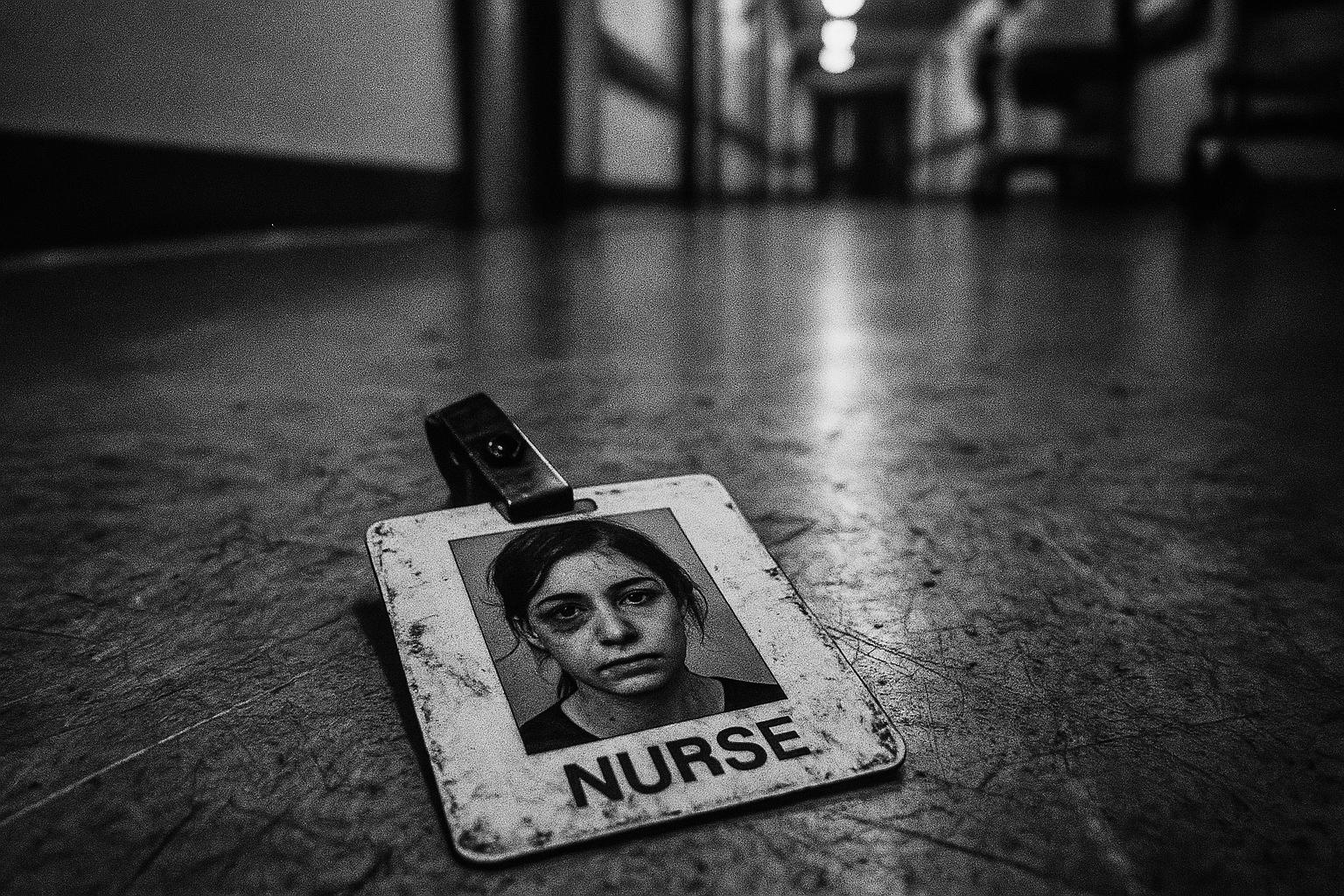

The human toll is stark. Nurses who spoke to the union described being punched, spat at, threatened with acid and, in one case, having a gun pointed at them. A senior sister in an east London A&E who was knocked unconscious after being punched said the violence was “just constant”, and a senior charge nurse in the East Midlands described being struck “square in the face” by an intoxicated patient. These first‑hand accounts have been used by the RCN to illustrate how routine clinical environments can quickly become unsafe for staff.

Union leaders and frontline clinicians link the violence to system pressures. The RCN warns that prolonged waits, corridor care and understaffed teams are creating frustration among patients — including some who would previously have been placid — and that that frustration is increasingly expressed as aggression towards staff. The college has also highlighted a sharp rise in mental‑health presentations to A&E and lengthy waits for specialist beds, arguing that inadequate community mental‑health capacity is a key contributor to pressure on emergency departments.

The consequences for the workforce are immediate and long term. RCN officials say physical and psychological injury from assaults leads to lengthy absences and, in some cases, people leaving the profession entirely. A separate survey cited by UNISON and Nursing Times found extremely high levels of physical assault experienced by nurses and midwives, with many reporting repeated or daily incidents; unions warn this undermines recruitment and retention and damages morale and patient care.

The government has described the reports as “appalling” and set out steps it says will help protect staff. The Health and Social Care Secretary said he had reaffirmed his commitment to standing with frontline workers and outlined measures including a graduate recruitment guarantee and enhanced victim support, training and security measures. More detailed proposals published by the Department for Health and social care and reported in professional press include mandatory national recording of incidents, trust‑level reporting on progress, analysis to identify groups at greater risk and powers for staff to refuse treatment when abused. Ministers say perpetrators should face the full force of the law.

Political and local responses vary. The Liberal Democrats have called for a panic‑button system linking A&E staff directly to their nearest police station, while some hospital trusts have trialled or expanded physical security measures such as increased patrols, CCTV and body‑worn cameras after local investigations showed rising assault figures. Campaigners and unions, however, argue that such measures are necessary but insufficient without simultaneous investment to cut waiting times and expand community and mental‑health services.

Experts and union leaders urge a two‑pronged approach: immediate protective measures and a longer‑term strategy to remove the pressures that precipitate aggression. The RCN has called for urgent investment in community mental‑health nursing and a comprehensive plan to end corridor care, arguing that without tackling the underlying workforce shortages and service gaps the rise in assaults will continue and could jeopardise wider NHS reform plans. Nursing bodies and unions are pressing for clearer, consistent national data so policy responses can be targeted where staff are most at risk.

Protecting clinical staff, the unions say, will require a sustained political and operational commitment: better surveillance and reporting of attacks, robust support and training for staff, rapid policing responses where appropriate, and the workforce and service changes needed to reduce delays and overcrowding. Absent that combination, the increasingly frequent and severe assaults on A&E teams risk becoming another entrenched consequence of a health service under strain.

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – 1, 2, 3

- Paragraph 2 – 1, 2, 3

- Paragraph 3 – 1, 3, 4

- Paragraph 4 – 1, 7

- Paragraph 5 – 1, 6, 5

- Paragraph 6 – 1, 5, 4

- Paragraph 7 – 4, 3, 6

- Paragraph 8 – 6, 7, 1

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.irishnews.com/news/uk/nurses-facing-abhorrent-violence-levels-while-in-ae-5KMTP67QUJOBBA7IOJLCEYRLCA/ – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.the-independent.com/news/health/nurses-violence-nhs-hospitals-eds-b2805562.html – The Independent reports on an RCN investigation stating that violence against A&E staff has risen sharply, with 4,054 recorded cases of physical assault in 2024 across 89 trusts compared with 2,093 in 2019. Nurses described being punched, spat at, threatened with acid and having a gun pointed at them. The RCN warned that long waits, corridor care and chronic staffing shortages are fuelling patient anger and increasing attacks. Health Secretary Wes Streeting condemned the violence and outlined measures including support and training. The Liberal Democrats suggested panic buttons linking A&E staff directly to police to improve security and recruitment concerns.

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/aug/12/ae-nurses-attacks-rise – The Guardian highlights RCN FOI findings that attacks on A&E nurses nearly doubled between 2019 and 2024, from about 2,122 to 4,054 incidents, attributing rises to prolonged waits, overcrowding and staff shortages. Reports include punching, spitting, threats involving weapons and acid, and staff described feeling unsafe. Hospitals are increasing security measures such as guards and CCTV while the RCN called for government action to end corridor care and tackle workforce deficits. Health leaders warned violence undermines retention and patient care. The article stresses the need for systemic NHS reform to protect staff and restore safe working conditions and public confidence.

- https://www.rcn.org.uk/news-and-events/Press-Releases/Urgent-mental-health-investment-needed-amid-crisis-level-A-and-E-pressures-130525 – The Royal College of Nursing press release reports findings from FOI requests showing a sharp increase in mental health presentations to A&E and lengthy waits for specialist beds, with some patients waiting over 12 hours or days. The RCN calls for urgent investment in community mental health nursing to relieve A&E pressures and protect patient dignity. It warns that staff are exhausted and delivering care in inappropriate settings, heightening risk of distress and aggression. The release urges government action to expand mental health capacity, improve workforce recruitment and retention, and include measures in the urgent and emergency care improvement plan.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-68022014 – A BBC investigation found thousands of physical assaults on hospital staff in Kent and Sussex, with incidents rising from 1,159 in 2018 to 1,714 in 2022. Nurses reported being spat at, punched and hit, prompting some trusts to trial body-worn cameras and other security measures. The report highlighted that anger and frustration over waiting times can fuel violent behaviour and that many employers lack comprehensive training or support for assaulted staff. Government responses include increased sentencing for those who attack emergency workers, but unions argue more prevention, staffing and systemic reforms are needed to protect frontline healthcare workers and public.

- https://www.nursingtimes.net/workforce/streeting-unveils-measures-to-tackle-violence-against-nurses-09-04-2025/ – Nursing Times reports Health Secretary Wes Streeting announced measures to tackle violence against NHS staff, including mandatory national recording of incidents, analysis to identify groups at greater risk, and trust-level reporting on progress to protect staff. Streeting emphasised that staff should be able to refuse treatment if abused and called for zero tolerance. The article notes plans for enhanced support including security training, trauma support and career development measures as part of wider workforce reforms. It situates the announcement amid rising reports of assaults on nurses and union pressure to address long waits, corridor care and staffing shortages driving aggression.

- https://www.unison.org.uk/news/press-release/2025/03/nurses-and-midwives-subjected-to-violence-at-work-on-a-daily-basis-according-to-unison-nursing-times-survey/ – UNISON’s press release summarises a joint Nursing Times survey finding that over nine in ten nurses and midwives had experienced physical violence at work, with many assaulted daily. Incidents included punching, biting, spitting, choking and stabbing, often by patients. The union called for urgent employer action, noting that 63% of staff had been attacked in the previous 12 months and that assaults harm retention, morale and patient care. UNISON urged practical measures beyond posters, like training, reporting systems, personal safety equipment and robust employer accountability to prevent assaults and support staff affected by violence, including counselling, incident follow-up and sanctions.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative presents recent data from 2024, with the earliest known publication date of similar content being 24 January 2024. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) compiled figures from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests across trusts, indicating a high freshness score. However, similar reports have appeared in the past, such as the BBC’s coverage on 24 January 2024, which may suggest some recycled content. ([bbc.com](https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-68022014?utm_source=openai)) The RCN’s involvement typically warrants a high freshness score due to their authoritative role in healthcare reporting. No significant discrepancies in figures, dates, or quotes were found. The update of data from 2019 to 2024 justifies a higher freshness score but should still be flagged. ([standard.co.uk](https://www.standard.co.uk/news/health/nurses-nhs-rcn-liberal-democrats-wes-streeting-b1242495.html?utm_source=openai))

Quotes check

Score:

7

Notes:

Direct quotes from nurses and union leaders are included. The earliest known usage of similar quotes appears in the BBC’s coverage on 24 January 2024. ([bbc.com](https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-68022014?utm_source=openai)) Variations in wording were noted, such as ‘punched in the head’ versus ‘punched in the face,’ which may indicate paraphrasing or different reporting. No online matches were found for some quotes, suggesting potential originality or exclusivity.

Source reliability

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative originates from The Irish News, a reputable publication. The RCN, a credible organisation, provided the data, enhancing the report’s reliability. No unverifiable entities are mentioned.

Plausability check

Score:

8

Notes:

The claims align with previous reports of violence against NHS staff, such as the BBC’s coverage on 24 January 2024. ([bbc.com](https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-68022014?utm_source=openai)) The narrative includes specific details, including direct quotes and statistics, supporting its plausibility. The language and tone are consistent with typical healthcare reporting. No excessive or off-topic details are present.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative presents recent and relevant data from a reputable source, with direct quotes and specific details supporting its claims. While some content overlaps with previous reports, the inclusion of updated data and the involvement of credible organisations like the RCN and The Irish News enhance its credibility.