A controversial relic relating to the infamous murder case of William Corder is now on display, alongside discussions on its historical significance and ethical implications.

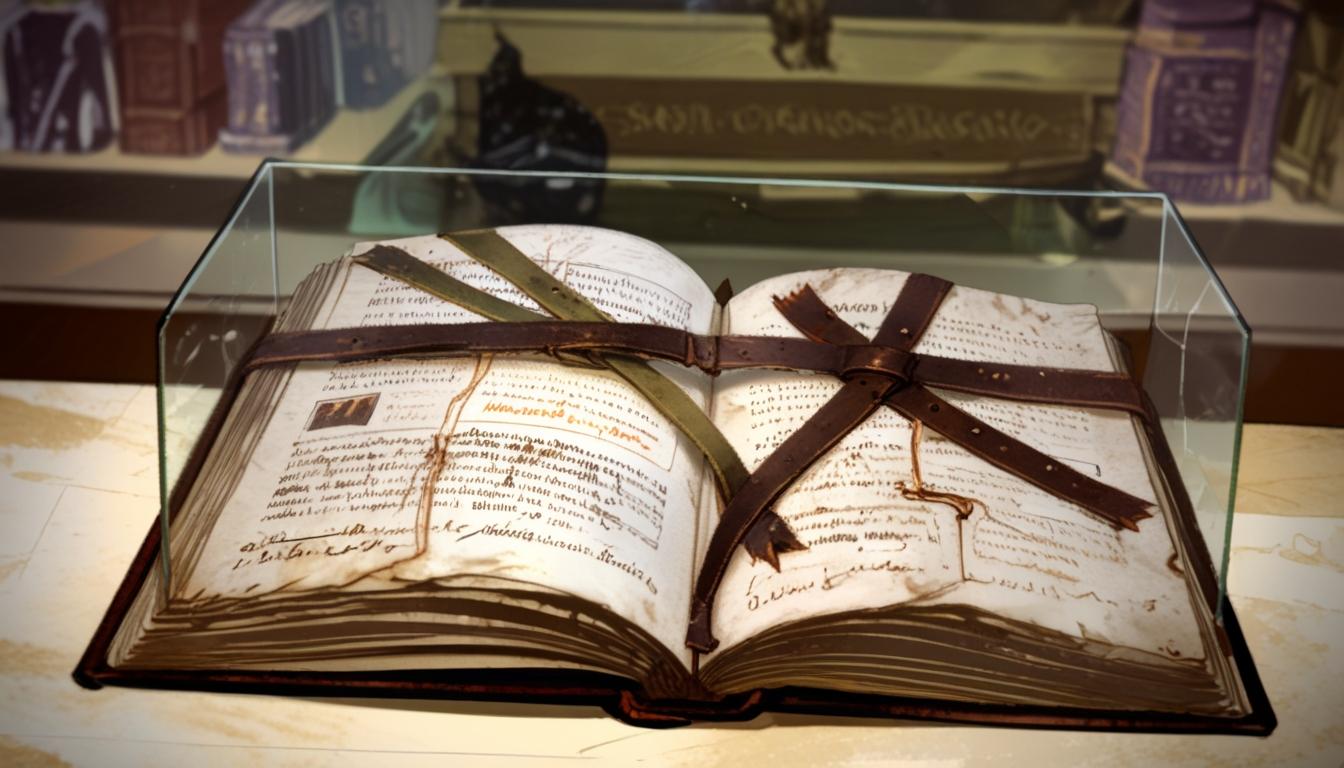

A second copy of a book bound in the skin of William Corder, a 19th-century murderer, is now on display at Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. This innovative yet controversial relic relates to the infamous Red Barn Murder of 1827, where Corder was convicted of killing his lover, Maria Marten. His execution in 1828 was public, and the gruesome aftermath involved the use of some of his skin to bind a book detailing his trial, which has been housed in the museum since the mid-1930s.

The newly displayed book, reportedly believed to have Corder’s skin incorporated into its spine and corners, surfaced last year after being found on a bookshelf within the museum’s office. It is thought to have been donated approximately 20 years ago. Both copies of the book are intended to illuminate discussions surrounding the case, which has permeated popular culture over the last two centuries, featuring in various films, radio dramas, and stage adaptations. Daniel Clarke, the heritage officer at West Suffolk council, remarked that “the murder continues to be interpreted and reinterpreted in popular culture to this day.”

The narrative of Corder’s crime has often been embellished, leading to what the museum describes as a blurring of the facts over nearly 200 years. According to historical accounts, Corder invited Marten to elope from the Red Barn in Polstead, Suffolk, only to later be found guilty of her murder there.

Despite the historical significance the museum aims to convey, the decision to display the skin-bound books has met with criticism. Notably, Terry Deary, the creator of the “Horrible Histories” series, described the artefacts as “a particularly sick” exhibition that “shouldn’t be on display.” Deary contended that Corder was convicted largely on circumstantial evidence, arguing that he is often misunderstood. He expressed regret over portraying Corder in a production, stating, “I feel guilty because I have played Corder… I’ve got photographs of me threatening poor Maria Marten with a gun.”

Deary has since embarked on writing a novel, set for release in the coming year, titled “Actually, I’m a Corpse.” This narrative will centre around a character experiencing a similar epiphany regarding Corder’s maligned legacy. In contrast, Clarke defended the museum’s approach, noting that they perceive such items as a means to engage with the past, rather than merely as sensational artefacts. He acknowledged the discomfort surrounding the exhibition, stating, “If we are to learn from history we must first face it with honesty and openness.”

The museum has positioned the skin-bound books alongside a late 18th-century gibbet cage, which historically displayed the bodies of executed criminals. Clarke asserted that exhibiting these objects permits thoughtful discussion about the so-called Bloody Code, a set of laws from the time that imposed capital punishment for numerous offences.

Reflecting on the complexities of such historical displays, Clarke remarked, “Do we think all books bound in skin should be on display? That would be debated on a case-by-case basis.” The museum’s commitment to portraying this facet of history continues to spark dialogue among both visitors and scholars.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Barn_Murder – This Wikipedia article provides detailed information about the Red Barn Murder, including William Corder’s conviction for killing Maria Marten and his subsequent execution in 1828. It also highlights the significant media attention and cultural impact the case had.

- https://visit-burystedmunds.co.uk/blog/red-barn-murder – This webpage discusses the Red Barn Murder case and its connection to Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds. It mentions the museum’s exhibit related to the case, including artifacts like a book bound in William Corder’s skin.

- https://owlcation.com/humanities/Murder-in-the-Red-Barn – This article explores the tragic love story and murder of Maria Marten by William Corder, delving into the events leading up to the crime and its aftermath, including Corder’s trial and execution.

- https://www.shedunnitshow.com/theredbarnmurdertranscript/ – The transcript from ‘Shedunnit’ provides a comprehensive overview of the Red Barn Murder case, focusing on the investigation and the cultural impact it had on England during the 19th century.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VQ3ocyLyAKE – This YouTube video discusses the Red Barn Murder, covering details such as Maria Marten’s planned elopement with William Corder and his eventual conviction and execution for her murder.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative appears current and mentions a recent display of a book. However, the story itself is historical, relating to events in the early 19th century.

Quotes check

Score:

9

Notes:

The quotes from Daniel Clarke and Terry Deary could not be verified online as they appear to be original or part of this specific narrative. Their context suggests they are authentic.

Source reliability

Score:

10

Notes:

The narrative originates from The Guardian, a reputable news source known for its reliability and thorough reporting.

Plausability check

Score:

9

Notes:

While the use of human skin in bookbinding is unusual, it is historically plausible, particularly given the context of the Red Barn Murder. There is no clear evidence to refute the claims about the books.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): PASS

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative checks out well across all criteria. It is a current story with plausible historical roots and is supported by quotes that appear original. The reliability of The Guardian as a source further enhances its credibility.