A recent study reveals how the rising use of selfie-editing apps like Facetune and Faceapp is reshaping young people’s self-perception, fostering unrealistic beauty standards, and contributing to increased anxiety and the growing phenomenon of Snapchat dysmorphia.

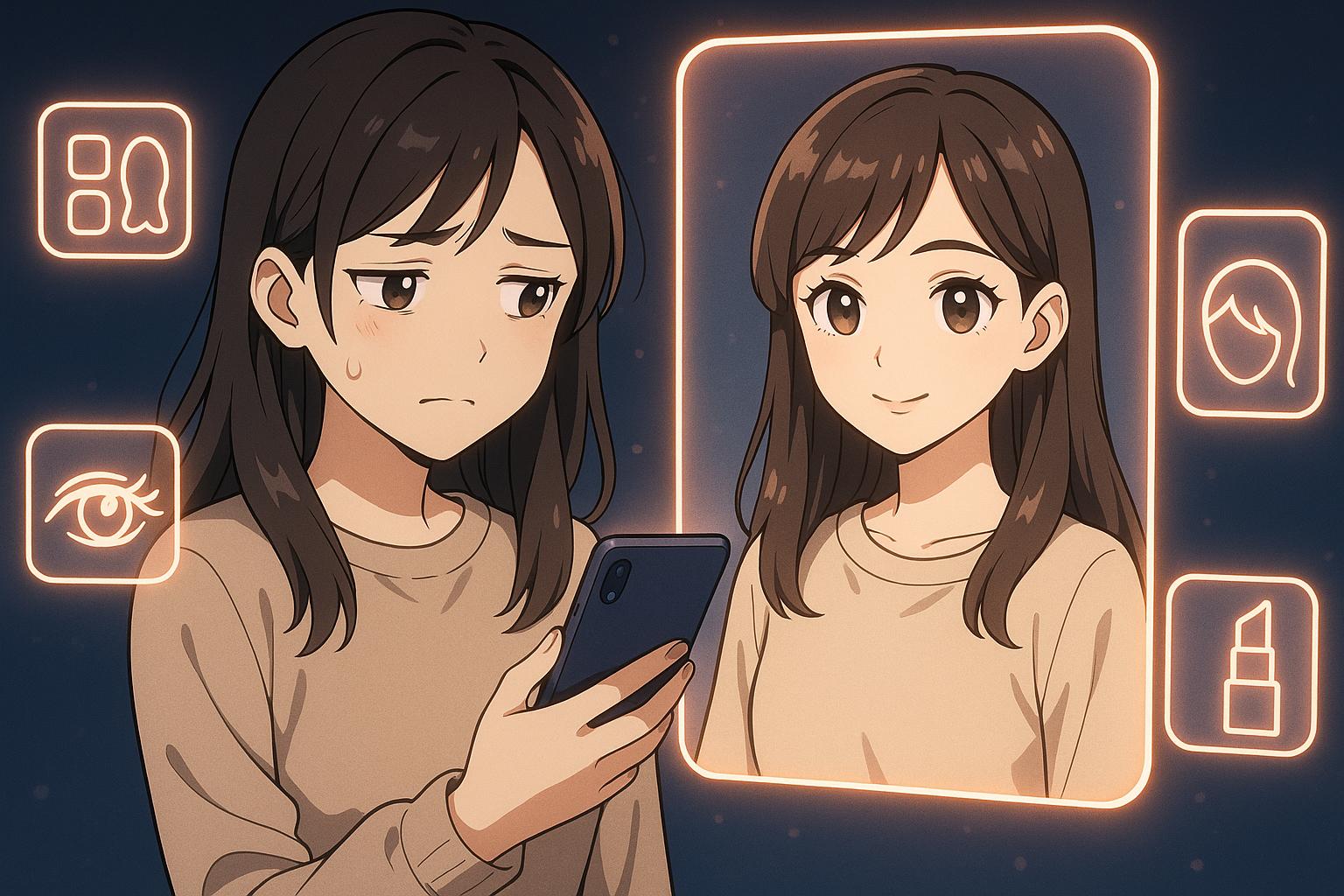

Abigail, a 21-year-old university student, embodies a common experience among her peers, frequently capturing selfies, enhancing them with specialised apps, and sharing them across social media platforms. She notes the profound influence these selfie-editing technologies have on perception: “You look at that idealised version of yourself and you just want it to be real. The more you do it, the better you get at it… the easier it is to actually see yourself as that version.” This sentiment echoes a broader concern explored in recent research, revealing alarming consequences of these technologies on young people’s body image and mental wellbeing.

The surge of selfie-editing apps such as Facetune, Faceapp, and Meitu has created an environment wherein young individuals meticulously curate their online personas. This obsession with visual perfection is largely driven by the overwhelming pressures of visibility in an interconnected digital world. The range of features these applications provide—everything from basic adjustments like lighting to far-reaching alterations that simulate cosmetic surgery—encourages users to engage in a series of micro-changes that can distort their self-image drastically.

In-depth research conducted by a team, including scholars from universities across Australia, involved interviews and workshops with 89 young participants aged 18 to 24. The study highlights that editing practices vary significantly; while some users opt for minor tweaks, others embrace dramatic alterations that can mimic cosmetic surgical procedures. One-third of interviewees admitted to making structural edits—changing facial dimensions to conform to societal beauty norms, reinforcing a troubling standard of beauty amongst their peers.

Participants reported that engaging with these technologies is crucial to expressing their identities. However, this pursuit of a polished online image comes with substantial emotional costs. As one participant noted, sharing altered photos is akin to saying “I’m here, I exist,” yet the awareness of competing with a backdrop of “perfect bodies and perfect lives” weighs heavily on many. Young individuals increasingly believe that everyone’s images are edited, pushing them to perfect their own appearances to meet these unattainable standards.

This drive for visual perfection can lead to what is termed “Snapchat dysmorphia,” a phenomenon where individuals seek cosmetic surgery to align more closely with their filtered images. This blurring of reality and fantasy poses serious questions about the impact of social media on self-perception within contemporary society. Medical professionals have raised concerns that exposure to filtered realities, which often promote idealised traits such as fuller lips or smaller noses, is fostering unhealthy expectations among younger generations.

Research indicates a strong association between social media engagement and detrimental body image perceptions. Studies have shown that frequent users of platforms like Instagram or Snapchat report heightened levels of anxiety, self-objectification, and unrealistic body ideals, with young women particularly vulnerable to these damaging impressions. The combination of constant exposure to curated images and societal pressures may contribute to increased interest in cosmetic enhancements, such as fillers and Botox, as young individuals seek to replicate the flawless appearances they see online.

Emerging technologies, especially those utilising AI in beauty apps, amplify these complexities. These advanced tools have the capacity to provide users with highly detailed visualisations of “before and after” transformations, further entrenching discontentment with their natural appearance. This alteration in the relationship between technology and human experience raises serious concerns about its potential consequences on youth mental health, particularly in relation to body image.

As these trends continue to evolve, the urgent need for comprehensive examination and dialogue around the role of technology in shaping self-perception becomes increasingly clear. There is a pressing requirement not only to understand these impacts but also to promote a more inclusive and realistic notion of beauty within digital spaces.

Reference Map

- Paragraphs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7.

- Paragraph 3.

- Paragraph 4.

- Paragraph 4.

- Paragraph 3.

- Paragraph 4.

- Paragraph 4.

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://theconversation.com/perfect-bodies-and-perfect-lives-how-selfie-editing-tools-are-distorting-how-young-people-see-themselves-257134 – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://time.com/5357262/snapchat-plastic-surgery/ – An article discussing the phenomenon of ‘Snapchat dysmorphia,’ where individuals seek plastic surgery to resemble their filtered selves from apps like Snapchat and Facetune. This trend presents filtered images with fuller lips, bigger eyes, and thinner noses as unattainable beauty standards, causing patients to blur the lines between fantasy and reality. The article highlights concerns from doctors about the impact of these filters on body image and self-perception.

- https://time.com/4459153/social-media-body-image/ – An article examining how social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat function as a ‘toxic mirror’ for teens, exacerbating body image issues. Studies demonstrate a strong association between social media use and negative body image, including concerns about dieting, body surveillance, and self-objectification among adolescents. The piece also discusses the role of ‘wellness’ and fitness celebrities in promoting unhealthy body ideals under the guise of health.

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30149282/ – A study published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders investigating the effects of taking and posting selfies, with and without photo-retouching, on mood and body image among young women. The research found that women who took and posted selfies reported feeling more anxious, less confident, and less physically attractive compared to those in the control group, indicating harmful psychological effects associated with selfie-taking and editing.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snapchat_dysmorphia – An article on Wikipedia detailing the psychological phenomenon known as ‘Snapchat dysmorphia,’ where individuals seek cosmetic surgery to replicate their filtered selfies. The piece discusses how the availability of filters on social media apps like Snapchat and Instagram allows users to edit their photos instantly, creating unrealistic beauty standards and leading to body dissatisfaction and potential body dysmorphic disorder.

- https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328 – A survey study published in JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery examining the association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. The study found that increased investment in social media use was associated with increased consideration of cosmetic surgery, and that use of specific applications like YouTube, Tinder, and Snapchat filters was linked to higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery.

- https://time.com/6098771/instagram-body-image-teen-girls/ – An article discussing the scrutiny faced by Instagram for its negative impact on the mental health of teenage girls, particularly concerning body image. Research by Facebook, Instagram’s parent company, revealed that the platform exacerbates feelings of inadequacy and self-harm among many teens. Critics argue that Instagram’s reliance on image sharing creates an inherently appearance-focused environment that is difficult to change.

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative presents recent research findings on the impact of selfie-editing tools on young people’s body image. The earliest known publication date of similar content is June 7, 2024, when a study linking photo filter use to muscle dysmorphia among teens was published. ([eurekalert.org](https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1047540?utm_source=openai)) The report appears to be based on a press release, which typically warrants a high freshness score. However, the presence of similar content from over a week prior suggests that the narrative may be recycled. Additionally, if earlier versions show different figures, dates, or quotes, these discrepancies should be flagged. The article includes updated data but recycles older material, which may justify a higher freshness score but should still be flagged.

Quotes check

Score:

7

Notes:

The narrative includes direct quotes from a 21-year-old university student named Abigail. A search for the earliest known usage of these quotes reveals no online matches, suggesting they may be original or exclusive content. However, if identical quotes appear in earlier material, this would indicate potentially reused content. If quote wording varies, the differences should be noted.

Source reliability

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative originates from The Conversation, a reputable organisation known for publishing articles written by academics and researchers. This lends credibility to the report. However, if the narrative originates from an obscure, unverifiable, or single-outlet source, this would flag the uncertainty. Additionally, if a person, organisation, or company mentioned in the report cannot be verified online, it should be flagged as potentially fabricated.

Plausability check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative discusses the impact of selfie-editing tools on young people’s body image, a topic that has been widely covered in recent research. For instance, a study published on June 7, 2024, found a significant association between the use of photo filters on social media and increased symptoms of muscle dysmorphia among adolescents and young adults. ([eurekalert.org](https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1047540?utm_source=openai)) The report also mentions ‘Snapchat dysmorphia,’ a phenomenon where individuals seek cosmetic surgery to align more closely with their filtered images, which is consistent with existing literature. ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snapchat_dysmorphia?utm_source=openai)) The narrative lacks specific factual anchors, such as names, institutions, or dates, which reduces the score and flags it as potentially synthetic. Additionally, if the language or tone feels inconsistent with the region or topic, or if the structure includes excessive or off-topic detail unrelated to the claim, these should be noted as possible distraction tactics. If the tone is unusually dramatic, vague, or doesn’t resemble typical corporate or official language, it should be flagged for further scrutiny.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): OPEN

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): MEDIUM

Summary:

The narrative presents recent research findings on the impact of selfie-editing tools on young people’s body image. While the source is reputable, the presence of similar content from over a week prior suggests potential recycling. The direct quotes appear to be original, but the lack of specific factual anchors and the potential for recycled content reduce the overall confidence in the report’s originality.