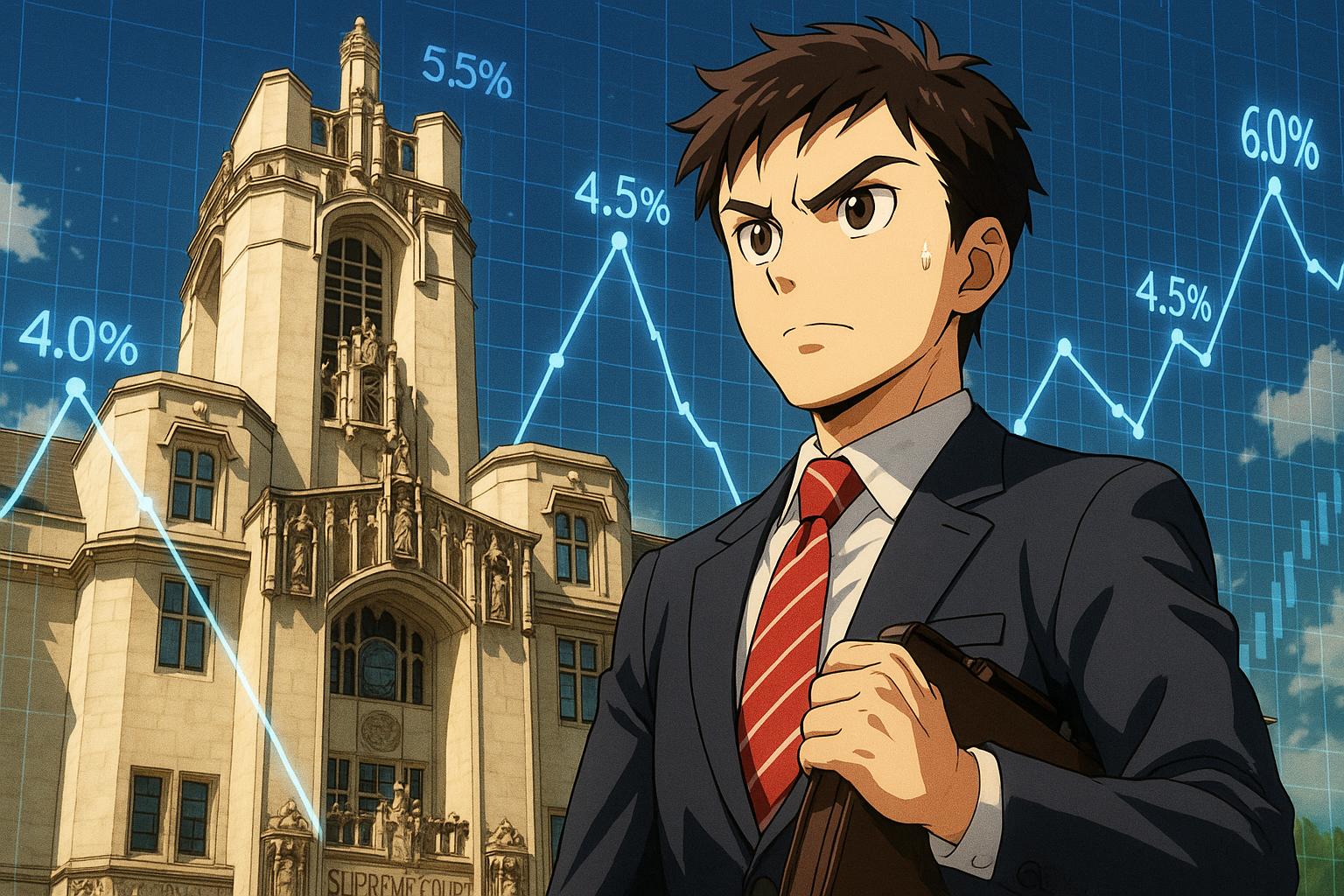

The UK Supreme Court will decide the fate of traders Tom Hayes and Carlo Palombo, whose convictions for manipulating Libor and Euribor rates are challenged amid allegations that their actions mirrored practices encouraged by top banking officials during the 2008 financial crisis.

The UK Supreme Court is set to deliberate on the cases of two former bankers, Tom Hayes and Carlo Palombo, who have been incarcerated for their involvement in the controversial rigging of interest rates tied to Libor and Euribor. This pivotal ruling carries implications not only for their individual convictions but also for the broader landscape of financial regulation and accountability. The traders assert their innocence, claiming they have been unjustly scapegoated in a scandal that has revealed significant misconduct from top banking officials and government entities.

Tom Hayes was once a trader at UBS and Citigroup, becoming the first individual to be imprisoned for manipulating the Libor rate in 2015. His conviction, handed out when he was just 35, branded him the “ringmaster” of a fraud conspiracy. He was sentenced to 14 years, though this was later reduced to 11 years in light of the intense scrutiny surrounding the case. Hayes’s conviction has been contentious, with persistent claims that the legal frameworks guiding the jury’s understanding of “dishonesty” were flawed. As both Hayes and Palombo now appeal at the Supreme Court, they argue that their actions, which involved selecting interest rates within a legitimate range, should not have been deemed criminal, especially given parallels with official banking practices encouraged amid the 2008 financial crisis.

The backdrop of this case is significant. During the financial upheaval, various central banks, including the Bank of England, reportedly urged banks to manipulate rates to create the illusion of stability in the market. This raised troubling questions about the system’s integrity when the smaller traders, like Hayes and Palombo, are prosecuted while high-level officials escape scrutiny. Evidence that emerged post-conviction suggests that the actions of Hayes and Palombo mirrored practices that were, at that time, commonplace and even tacitly endorsed by their superiors. Notably, the former shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, has voiced his concern that the traders are part of a broader narrative of unjust punishment compared to the lack of accountability faced by government officials.

The intricacies of how Libor and Euribor function add another layer of complexity to the case. Libor, crucial for shaping countless financial products globally, was based on the submissions of 16 banks about the cost of borrowing. Critics argue that Hayes and Palombo’s requests for their trading desks to report rates slightly favoured by their financial positions were not unique or unethical, yet the Serious Fraud Office asserted such actions demonstrated an intent to deceive. Hayes maintains that adjusting minor variances in rate submissions to achieve the bank’s interests was standard practice, and fundamentally different from outright manipulation.

Consequently, the ramifications of the Supreme Court’s ruling could extend far beyond the fates of these two traders. Legal experts warn that if the court finds in favour of Hayes and Palombo, it may set a precedent that could overturn numerous convictions related to similar financial misconduct. This could ignite calls for a public inquiry into the deeper issues surrounding the scandal, as many believe far more substantial misdeeds, rooted in institutional misconduct, remain unaddressed.

The appeal represents a potential turning point for not only Hayes and Palombo but also for the future of regulatory practices in the UK banking system. A ruling in their favour might compel a reevaluation of how financial improprieties are prosecuted, potentially signalling a movement towards greater accountability for those at the highest echelons of both the financial and regulatory landscapes. As the judgement is awaited, the case serves as a compelling reminder of the ongoing complexities and ethical challenges inherent in financial governance.

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [2], [4]

- Paragraph 3 – [6], [7]

- Paragraph 4 – [5]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [3]

Source: Noah Wire Services

- https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c3rp94jr79po – Please view link – unable to able to access data

- https://www.ft.com/content/fe48e89a-1395-4487-83f1-c45bbf3fa647 – Tom Hayes, a former UBS and Citigroup trader convicted of rigging the Libor benchmark rates, is challenging his conviction at the UK Supreme Court. Hayes argues that his original trial was ‘fatally compromised’ and that jury directions were ‘fundamentally wrong in law.’ Hayes, who served five and a half years in prison following his 2015 conviction, was the first person found guilty in the global Libor scandal. The Supreme Court hearing, which involves a panel of five senior judges, will consider two technical issues regarding Libor rate submissions. The Serious Fraud Office maintains that Hayes’s actions were dishonest, supported by documentary evidence and his own admissions. The Libor scandal, which led to banks incurring billions in fines, involved manipulating a critical interest rate that affected trillions in financial products. Hayes’s case is being heard alongside that of Carlo Palombo, another trader convicted of similar offenses related to Euribor.

- https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/trader-hayes-takes-libor-rate-rigging-appeal-uk-top-court-2025-03-25/ – Tom Hayes, a former trader jailed for manipulating the Libor rate, is appealing his conviction at Britain’s top court. Convicted in 2015, Hayes, along with another convicted trader Carlo Palombo, argues that their actions were not automatically dishonest as their convictions depended on a definition of Libor that prohibited taking commercial interests into account. Hayes contends that the jury in his trial was wrongly directed by the judge to consider submissions involving trading advantages as inherently dishonest, which he claims should be a matter for the jury. This appeal follows a significant U.S. decision in 2022 that cleared two Deutsche Bank traders of similar charges. Hayes initially received a 14-year sentence, later reduced to 11 years, and was released after serving approximately five and a half years. Palombo was sentenced to four years.

- https://apnews.com/article/27d7bda773aa629debbfa5acb69d176b – Tom Hayes, a former trader at Citigroup and UBS, lost his appeal against his conviction for manipulating the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) between 2006 and 2010. Hayes, 44, was labeled as the ringleader of the rate manipulation scandal and was the first individual convicted for such activities in 2015. He served half of an 11-year prison sentence before his release in 2021 and was also convicted in a U.S. court in 2016. Hayes maintains his innocence, similar to former Barclays trader Carlo Palombo, whose related case was also reviewed but not overturned. Despite arguments from their lawyers suggesting their convictions were unsafe, the UK’s Court of Appeal upheld the verdicts. In light of this decision, Hayes plans to take his case to the Supreme Court. LIBOR, a crucial rate influencing various loans, was manipulated by submitting false data, which emerged as a significant scandal in 2012. The rate has since been phased out, partly due to its role in exacerbating the 2008 financial crisis.

- https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/conviction-libor-trader-hayes-should-be-overturned-lawyer-tells-uk-court-2024-03-14/ – Tom Hayes, the first trader jailed for Libor rate rigging, is seeking to overturn his conviction, arguing that the trial judge made significant errors in jury instructions. Adrian Darbishire, Hayes’ lawyer, stated that the jury was wrongfully told that Libor rates could not reflect any trading advantage, which impacted their ability to assess Hayes’ honesty. Hayes, a former trader at Citigroup and UBS, was convicted of conspiracy to defraud by manipulating Libor rates from 2006 to 2010. Diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, Hayes has been attempting to challenge the Serious Fraud Office prosecution for nine years and was released on license in 2021 after serving part of an 11-year sentence. His case, alongside that of former Barclays trader Carlo Palombo, is being reviewed by the Criminal Cases Review Commission following a U.S. court decision that allowed consideration of trading positions when setting Libor rates. The SFO maintains that commercial considerations in Libor rate settings were intended to prejudice other market participants.

- https://www.the-independent.com/news/uk/crime/libor-rate-rigging-scandal-supreme-court-b2548825.html – The first trader jailed worldwide for Libor interest rate rigging has been left with a possible route to clear his name, despite being refused permission to appeal against his conviction at the UK’s Supreme Court. Tom Hayes, a former star Citigroup and UBS trader, was convicted in 2015 of conspiracy to defraud by manipulating Libor, a benchmark rate once used to price trillions of pounds worth of financial products globally. He appealed against his conviction earlier this year alongside Carlo Palombo, a former Barclays trader convicted in 2019 of skewing Libor’s euro equivalent, Euribor. On Tuesday the Court of Appeal refused to give Hayes and Palombo permission to appeal to the Supreme Court, however, it did confirm that the case raised a “point of law of general public importance”. This means that Hayes and Palombo can apply directly to the Supreme Court for permission to appeal. Following the announcement, Hayes said: “I’m delighted that, at the fifth attempt, the court has finally and correctly certified this as a point of law of public importance. Ex-bankers Carlo Palombo and Tom Hayes outside court (Lucy North/PA) (PA Wire) He added that rate traders “have long insisted that submitting numerically truthful values was truthful, genuine and honest. “Now the Supreme Court will have the opportunity to decide if the presence of commercial consideration made those truthful rates criminal. “It’s time for the UK legal system to now align with the rest of the world and for these miscarriages of justice to be corrected.” In a ruling in March, three judges dismissed the appeals, with Lord Justice Bean finding that jurors were not misdirected in Hayes‘ case. And at a short hearing on Tuesday, the same judge, sitting with Lord Justice Popplewell and Mr Justice Bryan, refused the pair permission to appeal at the Supreme Court. However, the three judges did rule the case involves a “point of law of general public importance”, keeping open the possibility of a challenge at the UK’s highest court. Lord Justice Bean said: “It should be for the Supreme Court to decide whether the point of law is one which it ought to consider in the light of the consistent series of decisions of the Court of Appeal.” The Libor rate was previously used as a reference point around the world for setting trillions of pounds worth of financial deals, including car loans and mortgages. It was an interest rate average calculated from figures submitted by a panel of leading banks in London, with each one reporting what it would be charged were it to borrow from other institutions. Hayes, who has maintained his innocence, spent five and a half years in prison and was released in January 2021. Palombo was jailed for four years. Additional reporting by agencies

- https://www.standard.co.uk/business/business-news/supreme-court-to-hear-cases-of-traders-jailed-over-raterigging-b1172903.html – Two former financial market traders jailed over interest rate benchmark manipulation will take bids to clear their names to the UK’s highest court. Tom Hayes, 44, a former Citigroup and UBS trader, was found guilty of multiple counts of conspiracy to defraud over manipulating the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (Libor) between 2006 and 2010. His case, alongside that of another jailed trader, Carlo Palombo, 45, was referred to the Court of Appeal by the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), which investigates potential miscarriages of justice. In a ruling in March, three judges dismissed the appeals, finding that jurors were not misdirected in Hayes’ case. The Serious Fraud Office opposed the appeals. Lord Justice Bean, who heard the challenges alongside Lord Justice Popplewell and Mr Justice Bryan, later refused the two permission to appeal at the Supreme Court but did say the cases involve a “point of law of general public importance”. On Thursday, a Supreme Court spokeswoman confirmed that permission to appeal had been granted and that the case would be listed in due course. Following the announcement, Hayes said: “I’m ecstatic. At the fifth attempt, the Supreme Court finally has the chance to address the aberration of the case in law that was used to imprison Ibor traders for the submission of numerically true interest rates to a survey conducted by a trade association. “The Ibor traders have long insisted that submitting numerically truthful values was genuine and honest. “Now the Supreme Court will have the opportunity to decide if the presence of commercial consideration made those truthful rates criminal. “It’s time for the UK legal system to now align with the rest of the world and for these miscarriages of justice to be corrected.”